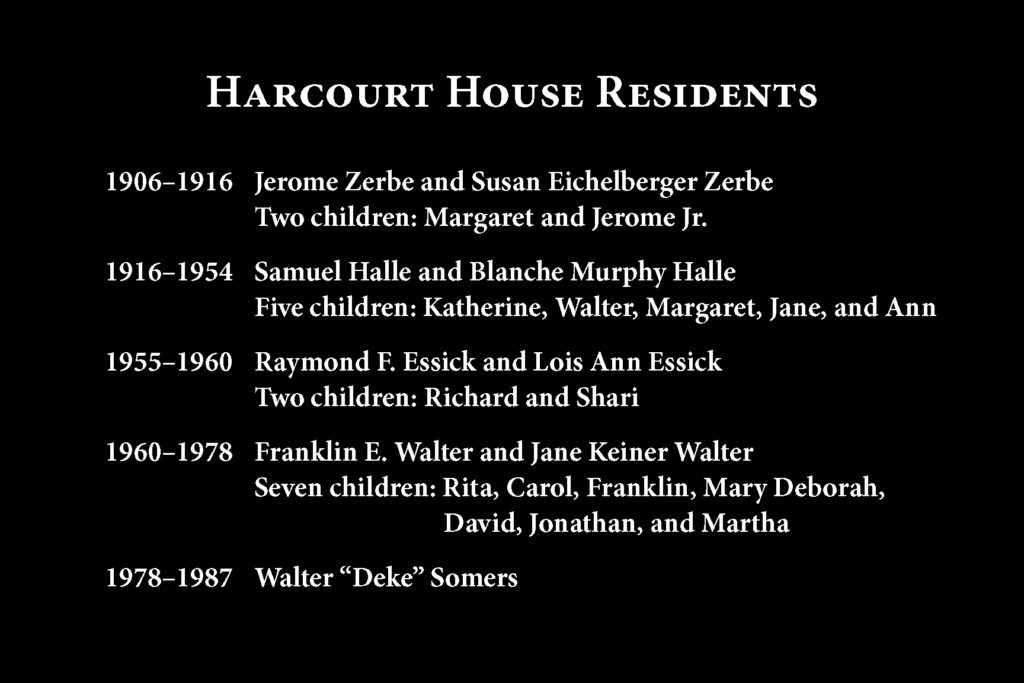

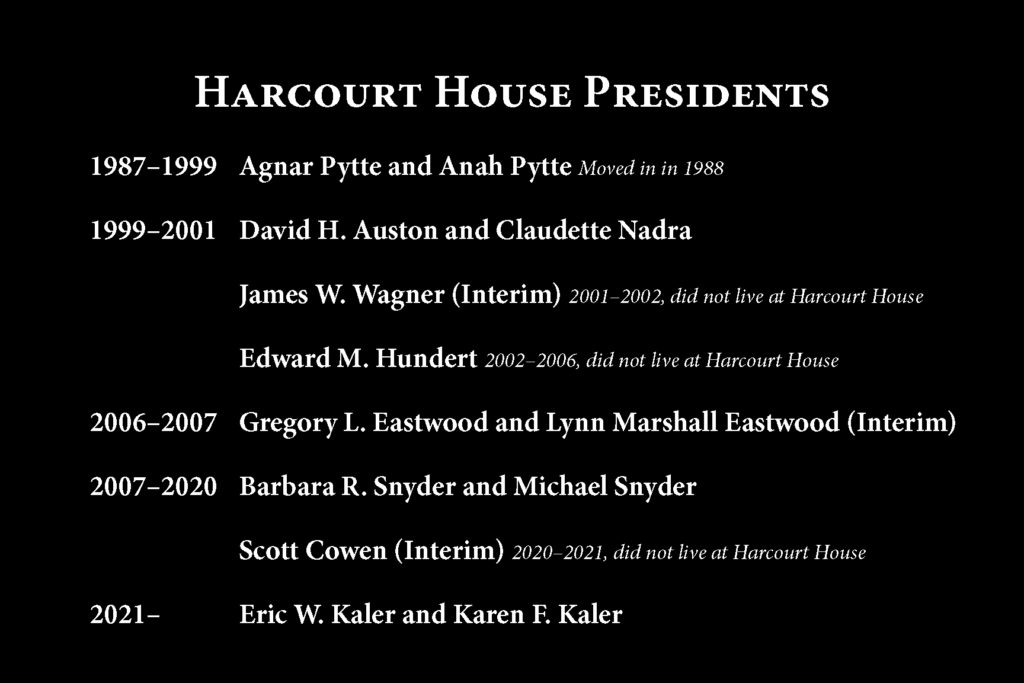

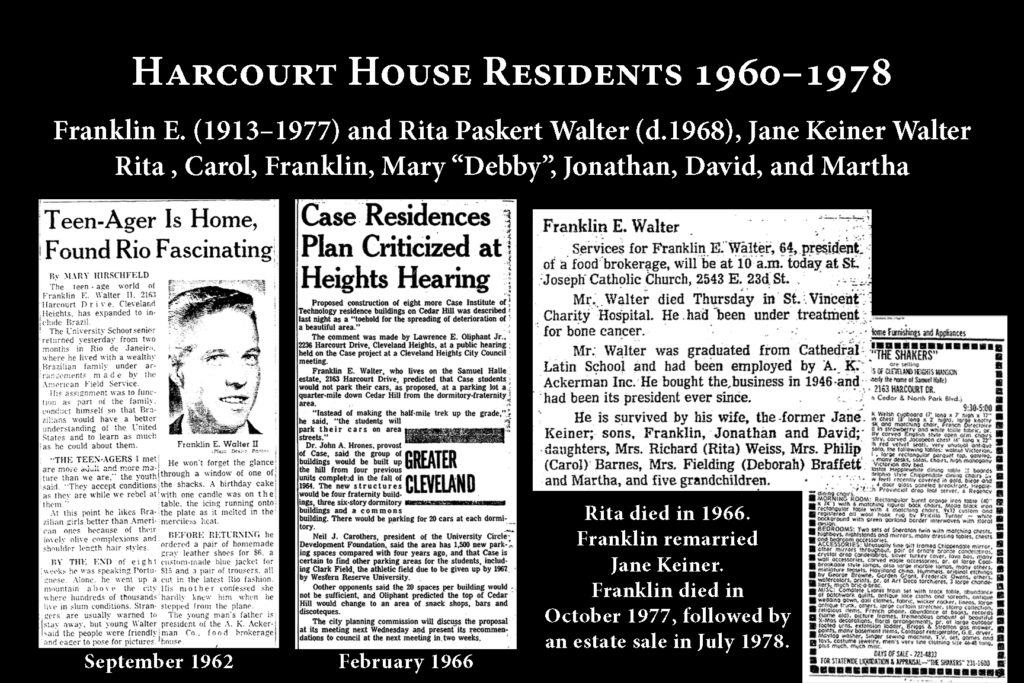

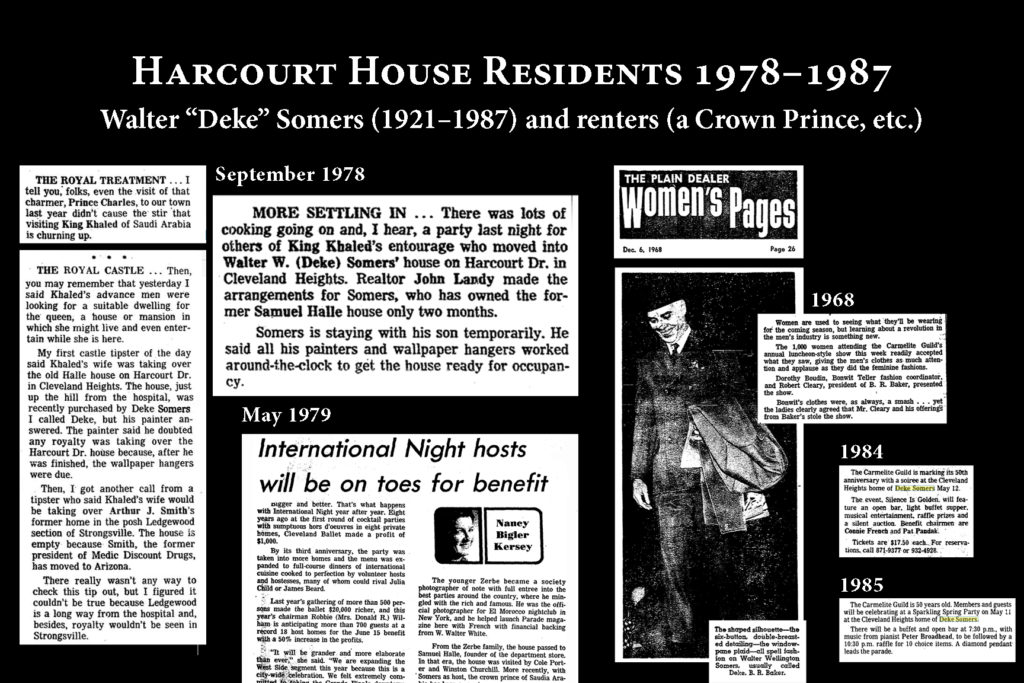

Harcourt House, previously known as the Zerbe/Halle Mansion, has been the official residence of presidents of Case Western Reserve University since 1988. The house, built in 1906 in Ambler Heights, in what is now Cleveland Heights, had a fascinating history before its current role.

Ambler Heights

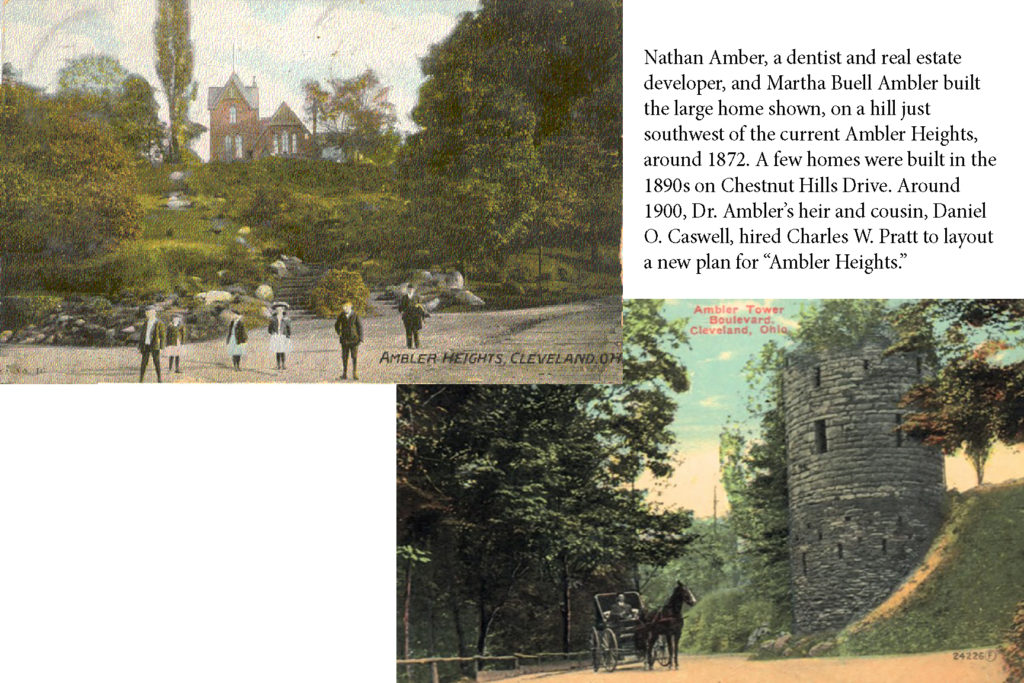

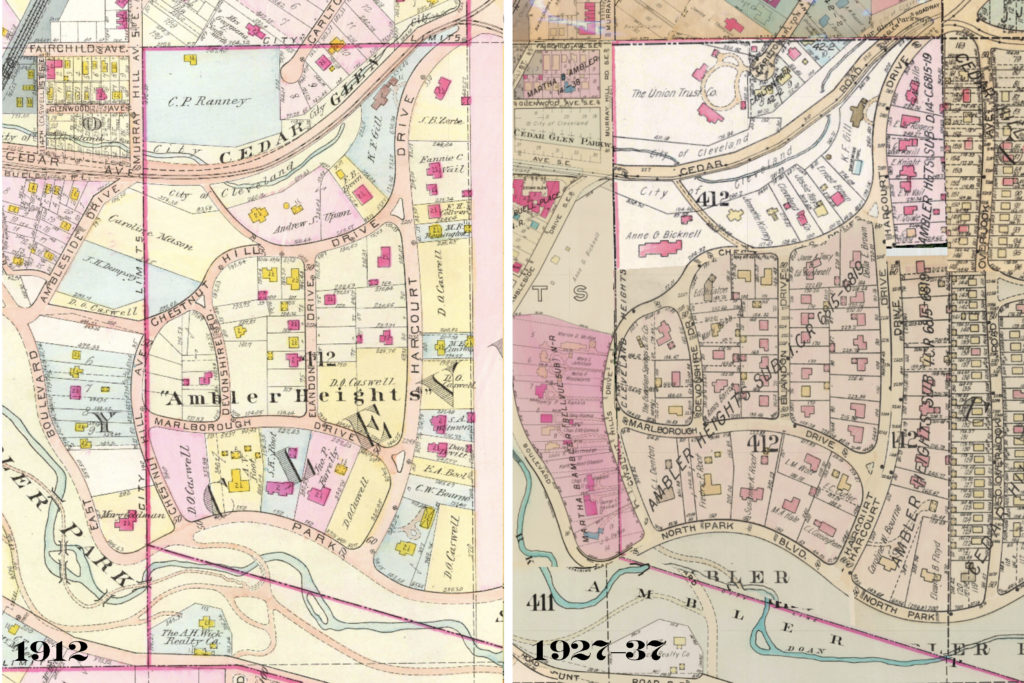

While University Circle began to thrive in 1882, and Millionaire’s Row on Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue had begun its decline, the land south of Cedar Glen Parkway and west of Doan Brook was still largely undeveloped. The land was owned by Dr. Nathan Ambler, among other holdings.

Nathan Hardy Ambler (1824-1888) was a Vermont-born dentist who joined the California Gold Rush in 1849. Similar to the stories of men who made fortunes selling shovels, Dr. Ambler provided dental care in exchange for gold dust. After three years, having amassed a large nest egg, he and his wife, Martha Buell Ambler, moved to Cleveland. He opened a dental practice, then began buying property on the outskirts of Cleveland. As the city grew, he resold the property, becoming quite wealthy. In 1868, sixteen years after arrival in Cleveland, he gave up his dental practice and became a full-time real estate developer. He was joined by his cousin and adopted son, and eventual heir, Daniel O. Caswell.

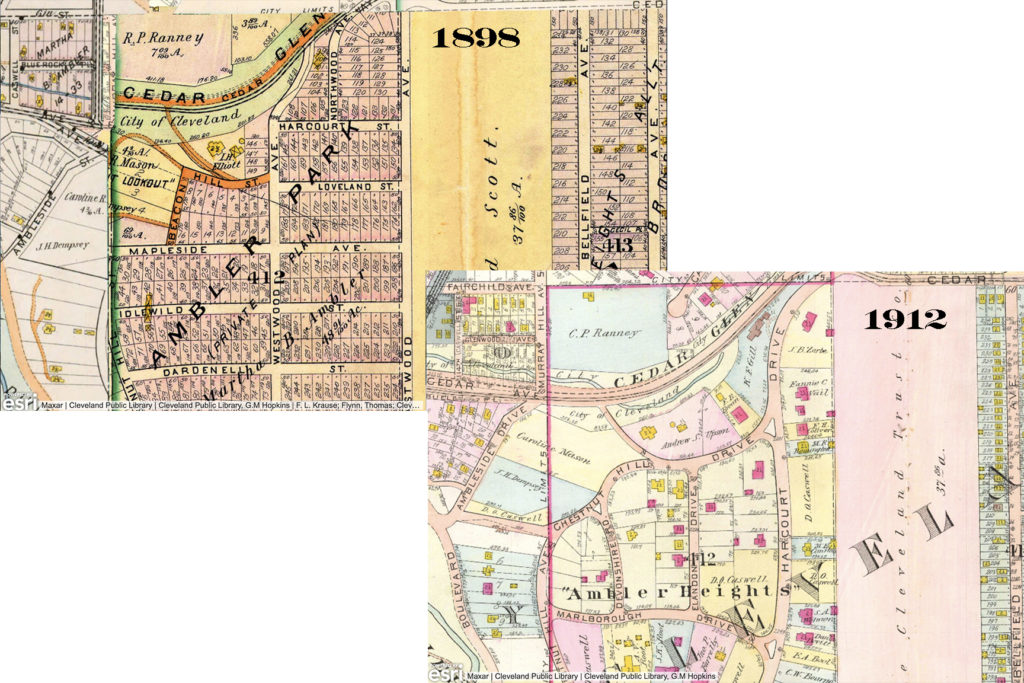

Ambler purchased land with quarries that would become Ambler Heights. (The Bowles-Eddy quarry was across the street from Harcourt House at Harcourt Manor; other small quarries were also in the neighborhood.) Around 1872, Dr. and Mrs. Ambler built a large home on a hill just southwest of the current Ambler Heights that is now the site of the Baldwin Filtration Plant. In 1892, after Dr. Ambler died and the nearby land was platted as Ambler Park, Martha Ambler donated about 25 acres along Ambler Parkway (now North Park Boulevard, for parkland. The land joined the growing green space around Cleveland. Four or five homes were built in the 1890s on Chestnut Hills Drive. Those houses’ fronts face away from the current street, as there was a carriage path in that direction. The other planned streets were not built.

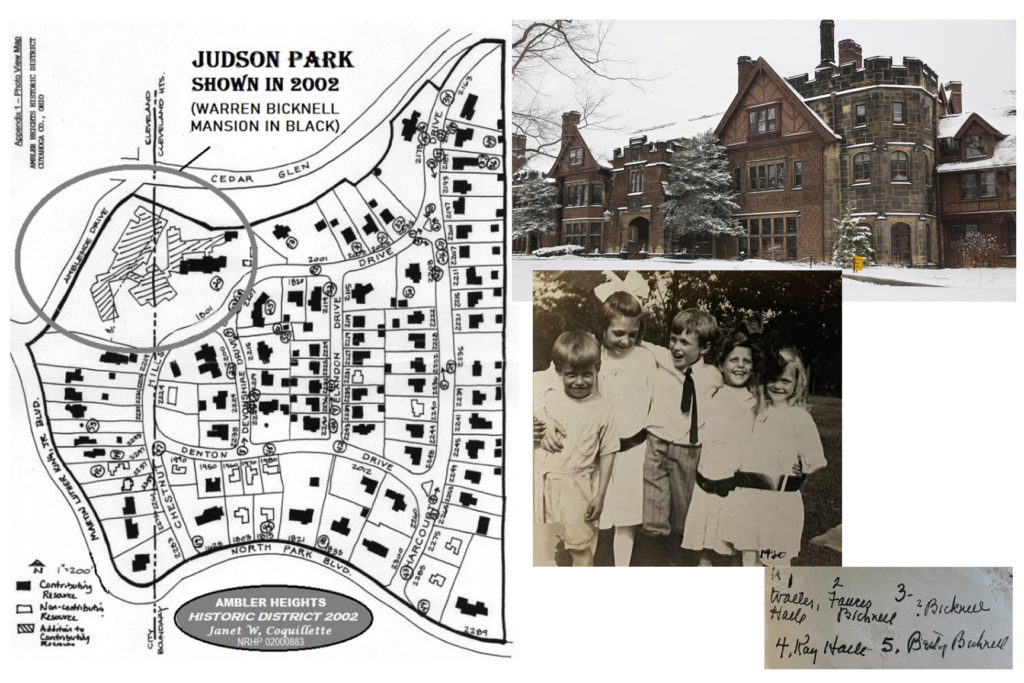

By 1900, Daniel Caswell hired Charles W. Pratt to lay out a new plan for “Ambler Heights.” He marketed the garden community to upscale clients, such as those who had formerly built homes on Cleveland’s Millionaire’s Row, who appreciated fresher air and the less industrial setting. After Caswell died in 1906, his widow, Elizabeth Stutte Caswell, handled the sales and further development of Ambler Heights. Today, 66 original, single-family, architect-designed private homes remain in Ambler Heights. Three or four original houses have been raised, and 13 homes were built after 1934.

Euclid Heights

In the meantime, Patrick Calhoun, a South Carolina native born in the home of his grandfather, Vice President John C. Calhoun, began planning a residential community on the former timber farm just to the east of the Ambler land. He had visited the Garfield Monument, looked out over the farmland, and immediately bought 200 acres for $50,000. (Fortunately, he didn’t name his garden city “Calhoun,” as his grandfather’s namesakes are now changing names.) Calhoun employed marketing skills in naming the development Euclid, after the avenue known as Millionaire Row, with the addition of Heights to emphasize the location, atop Cedar Hill, deemed to provide more healthful air.

The Euclid Heights Realty Company entered into an agreement with the Cleveland Electric Railway Company to bring a streetcar franchise up Cedar Glen in 1896. (Most Clevelanders did not have cars at that time, so the streetcar made the area—including Ambler Heights—accessible.

To further entice residents, Calhoun opened the Euclid Club in 1901, as Cleveland’s first professionally-designed 18-hole golf course. However, he didn’t own enough land for 18 holes. He leased, rent-free, land from avid golfer John D. Rockefeller for the upper nine. The Euclid clubhouse was designed by architectural firm Meade and Garfield.

In 1906, John Rockefeller permitted a streetcar line to bisect his property, connecting the Cedar Road line to Coventry Road. This line cut through the upper nine of the golf course. More consequential for the future of the golf course, Rockefeller, a devout Baptist, refused to allow his land to be used for golf on Sundays. Members who wished to play a full round on the most popular day for golf played the front nine, twice. Then Shaker Heights and Mayfield Country Clubs opened and provided competition. Euclid Golf Club disbanded in 1912, and residential development began.

Architect Abram Garfield

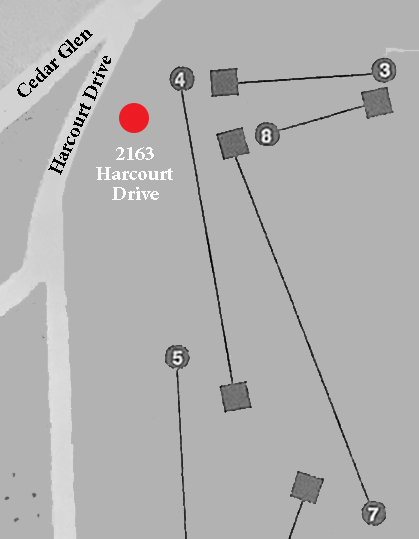

Harcourt House at 2163 Harcourt Drive, was built in 1906, among the first dozen or so houses in the neighborhood. It was first known as the Zerbe House, then as the Zerbe/Halle House, then Halle House, and now Harcourt House.

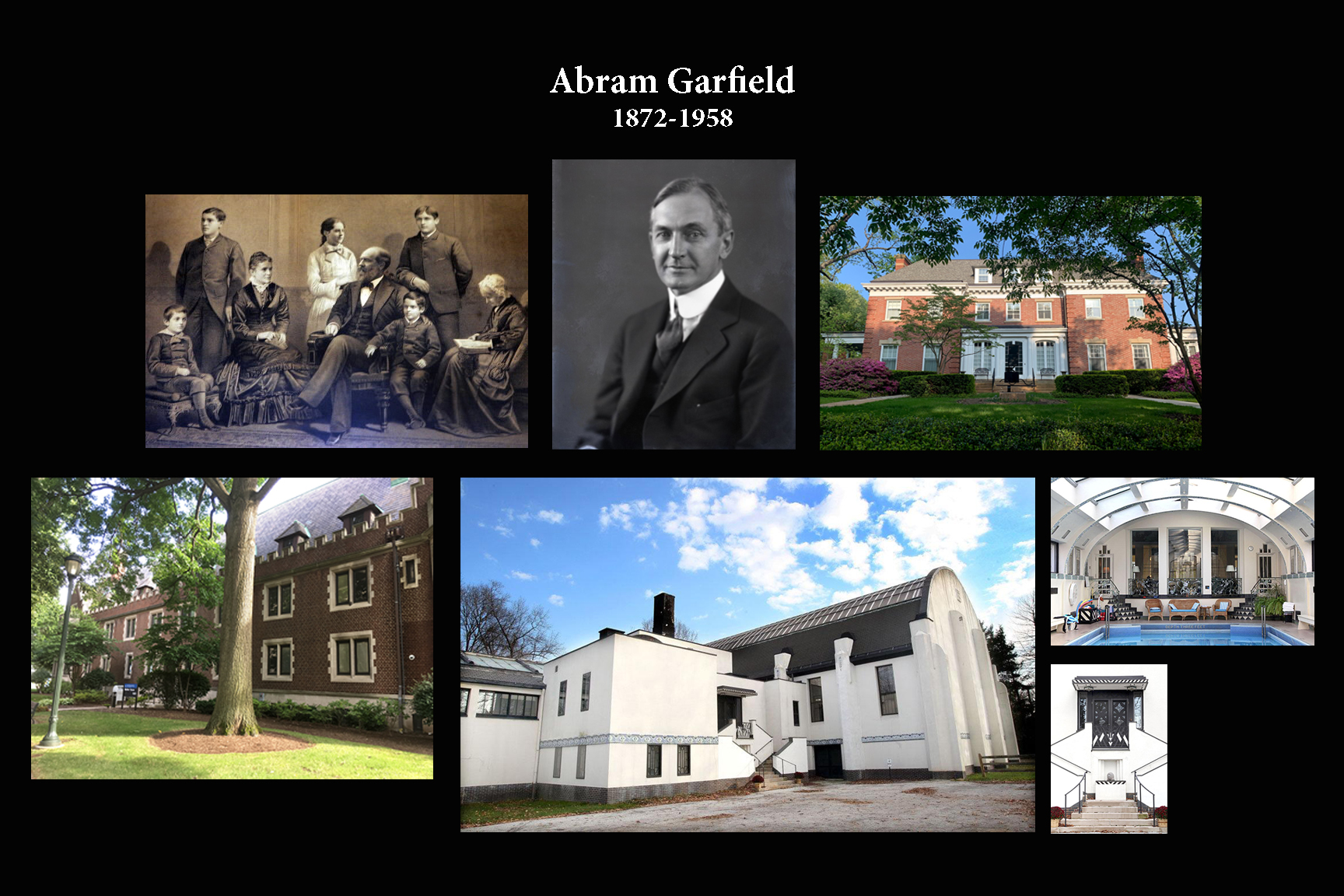

The house was designed by architect Abram Garfield (1872-1958). Garfield was a prominent Cleveland architect and the youngest son of President James Garfield, who was assassinated when Abram was eight-years old.

Garfield earned a BA from Williams College, then a BS in architecture degree from MIT. He formed the architectural firm Meade and Garfield in 1898 with Frank Meade. One of their first residential designs was the Howard White Mansion at 11105 Euclid Avenue, which, now owned by the Cleveland Clinic, is one of the four remaining mansions on Millionaires’ Row. Meade and Garfield designed many other fine Cleveland houses and, as mentioned, the Euclid Golf Clubhouse.

Abram Garfield went into business for himself in 1905 and was most known for his residential designs, but his work included other projects, such as the Mather House (1915) at what is now Case Western Reserve University. He showed his versatility in the 1930 design of his only Art Deco building, a recreation center for the Dudley S. Blossom estate. It is now called The Hangar, and is in Beachwood.

While considered an Ohio architect, a few notable designs are outside the state:

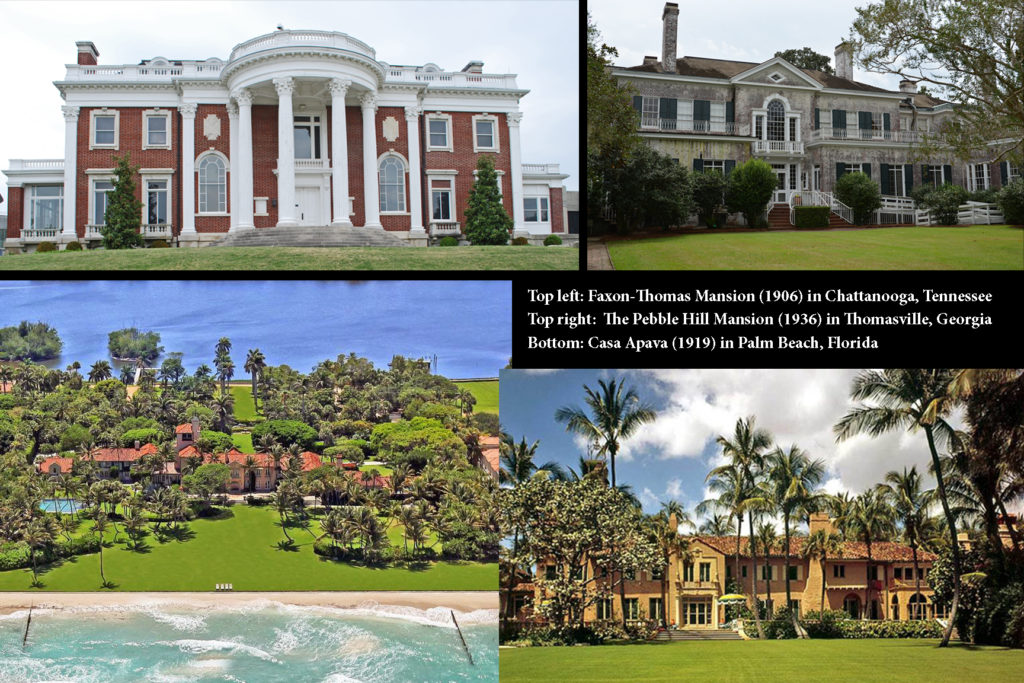

The Faxon-Thomas Mansion (1906) in Chattanooga, Tennessee, was designed for Ross Steele Faxon, a leader in the insurance field in Chattanooga. When Faxon moved to California in 1918, he sold the house to the widow of B.F. Thomas. Thomas originated the concept and developed the process of bottling Coca-Cola. The house is now the Hunter Museum of American Art.

The Pebble Hill Mansion (1936) in Thomasville, Georgia. The Pebble Hill plantation was purchased by Howard Melville Hanna. He gave it to his daughter, Kate in 1901. When the main house burned in 1934, Kate Hanna hired Garfield design the new mansion. It is now a museum.

Casa Apava (1919) in Palm Beach, Florida, was designed for Chester and Frances Payne Bingham Bolton. Casa Apava remains a residence, and sold for over $70 million in 2015.

Abram Garfield founded the Cleveland School of Architecture in 1929 and was its first president, serving until the school became part of Western Reserve University. He served as vice president until 1941, when he became a trustee. He was made an honorary lifetime member of the board in 1943, and received an honorary doctorate from Western Reserve University in 1945.

Garfield’s former partner, Frank Meade, was part of Cleveland society. He lived on Euclid Avenue and was founding president of the Hermit Club. He first designed on his own after the partnership with Garfield ended, then he partnered with James Hamilton to form Meade and Hamilton in 1911. Frank Meade designed three houses in Ambler Heights, and Meade and Hamilton designed another eight. Meade designed the home of the Kermode Gill family, across the street from Harcourt House at 2178 Harcourt. The Gills purchased the Ambler Heights land in 1906, the same year the Zerbe House was built, but that house took five years to build. The Herget family bought the home from the Gill family in 1954. It has been beautifully renovated as the home of its third owners, John and Anya Rudd.

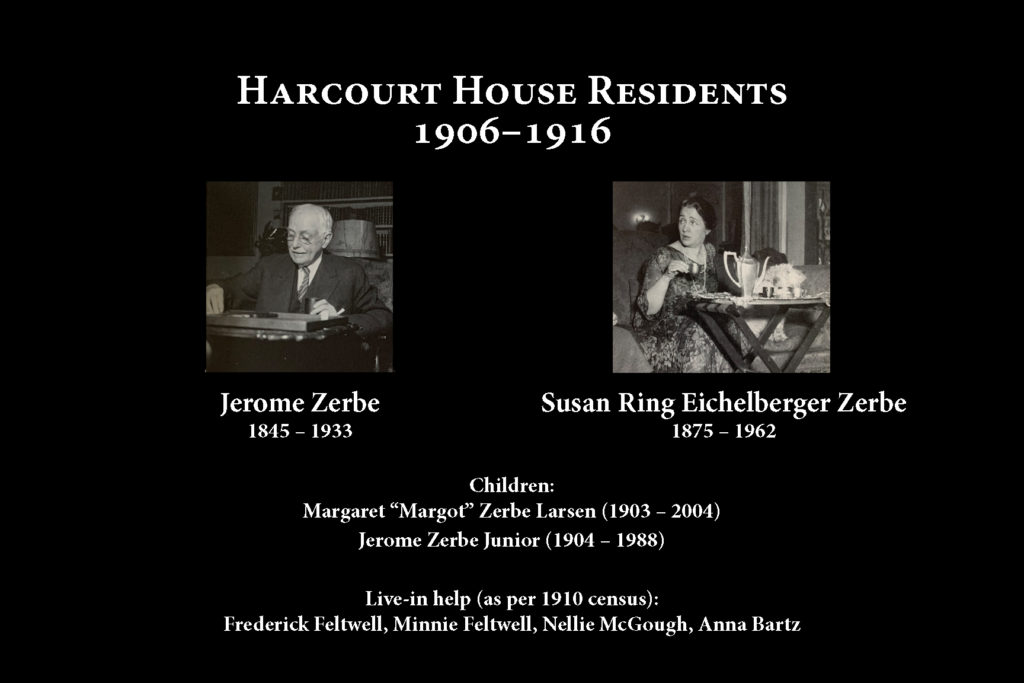

The Zerbe Family

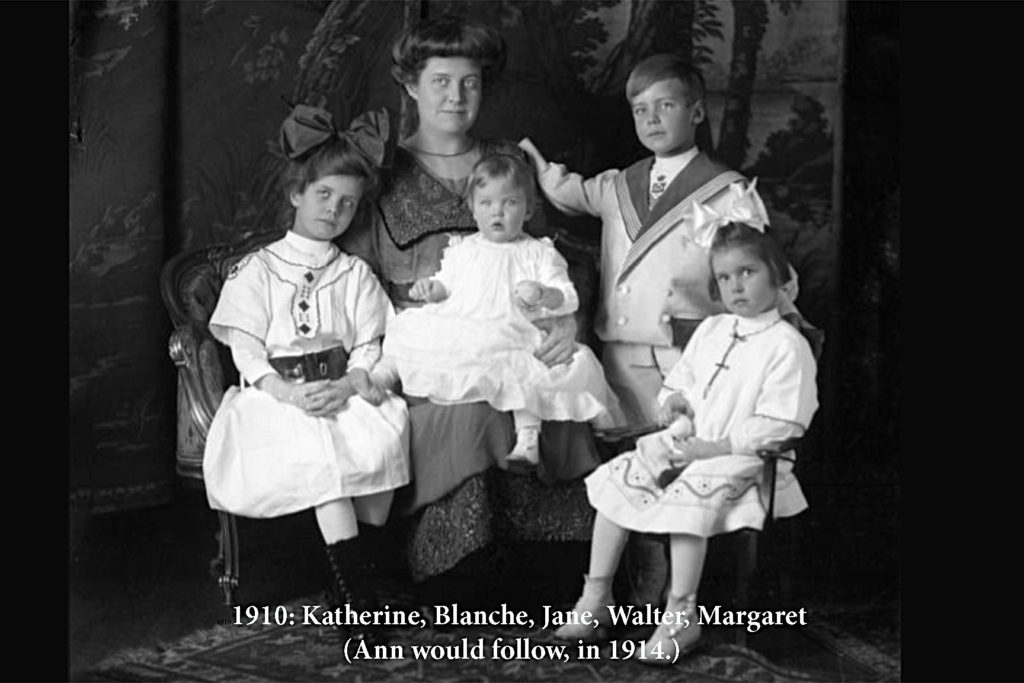

Harcourt House was built in 1906 as the home of Ohio and Pennsylvania Coal Company president Jerome Zerbe Sr. and his young family. Four years prior, in 1902, Jerome was a widower with an adult daughter, Lily (1875–1933), when he married Susan Eichelberger (who was six months younger than Lily). The couple had met at a reception given by Mayor and Mrs. Tom Johnson, and married six months after meeting. They would have two children, Margaret and Jerome Jr. Lily married Sheldon Cary, who would become president of Browning Crane Co., around the same time her father married. (Lily’s children and her young siblings are pictured in the photo below.)

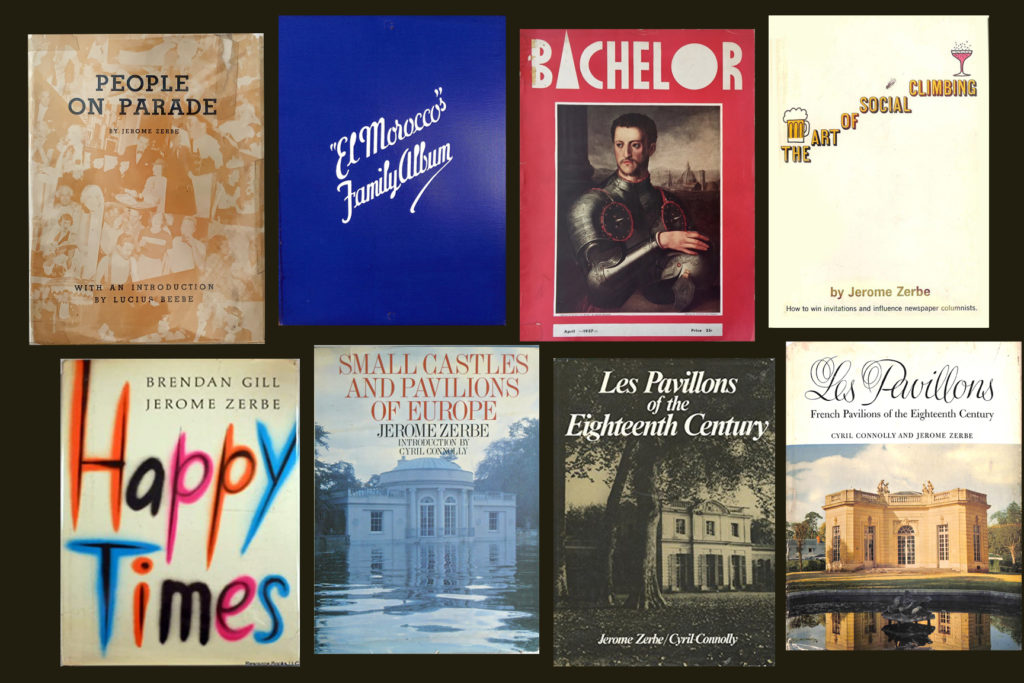

Jerome Jr. wrote an article titled “The House on Harcourt” for a 1952 book titled Curtain Call. His byline listed him as “Former Clevelander and a noted photographer; society editor for Town & Country.” Two decades later, he was interviewed by Studs Terkel for the 1970 book Hard Times: An Oral History of The Great Depression. A few years after that, he would collaborate with journalist and author Brendan Gill on a book about his life and work titled Happy Times. Perhaps due to the different intended audiences for the recollections, the stories express different viewpoints.

Curtain Call was a book written as part of a fundraising event for cancer research at the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine. The Curtain Call article written when Jerome was younger is, unexpectedly, more sentimental and describes a happier childhood than is portrayed in Happy Times. (The Happy Times text, first written as a profile for the New Yorker, may have reflected Gill’s style and attitudes more than Zerbe’s own.)

According to “The House on Harcourt,” the Zerbes lived in a home called Topridge in Euclid, with a view over farmlands toward Lake Erie. One day, the two young children were loaded into the family Garford automobile and driven to the big brick house that would be their home for eleven years. As Jerome Jr. described it:

The property, on the corner of Harcourt and Cedar, had a golf course of the Euclid Heights Country Club stretching behind it. Across Cedar, Howard Eells had built his handsome Tudor house to hold the family art treasures. To the west, directly across Harcourt, the property was too steep and narrow to build on, and we had a clear view across Cedar Glen. Across and a little farther to the south, the Kermode Gills built their fine place. Well I can remember the fun Billy Gill and I had as youngsters, hurling eggs down on the cars on Cedar Hill below. The neighborhood established itself very quickly and there were many children around our age——Benton Brown, Josephine Cannon, Ruthalia Keim, Walter Root, and, fairly close, Jane and Bill Palmer, the Halles, Jack Chandler, and my half-nieces and -nephew, Rachel, Shelley, and Jack Cary. Then there were Julia and Bud Eames and their older sister Clare, who was to become one of our country’s great actresses and die too young.

Golfers often stopped in for a visit, and our house seemed always full of people. Mother was a great beauty, and Father, although years older, was a very handsome man. Their group of friends were a spirited, attractive lot——the Price McKinneys, the Myron T. Herricks, the William Lowe Rices, the John Chandlers, the Belden Seymours, William G. and Samuel Mather, the Kenton Painters, Charles Brush and Charles Bingham. . . . .

Early Harcourt memories include that of sitting on Mother’s lap to watch the lamplighter light the gas lamps; of hearing calls for help in the night——for Cedar Glen was dangerous land then; the excitement of watching the Sunday evening balloon from Luna Park; of picnics with Uncle George and Aunt Frances Eichelberger and their friends on Lake Erie. When I was seven, the Joseph Eaton family moved from the East to Cleveland and into a house close to ours. Mrs. Eaton’s son, Winsor French, became my lifelong friend. . . .

Jerome Zerbe Jr., “The House on Harcourt,” Curtain Call (Cleveland: Gruber Foundation, 1952), 34-35

Winsor French (1904–1973) was the stepson of Joseph O. Eaton, chairman of the Eaton Axle and Spring Company, which would become the Eaton Corporation. The Eaton family lived at 2207 Devonshire in Ambler Heights. Joseph O. Eaton II had married Winsor’s mother, Edith, when she was a widow with four young children. Joseph and Edith would have four more children together.

Winsor’s parents would take Jerome along to the Hippodrome Theater on Euclid Avenue on Saturday afternoons. After seeing actress Maude Adams “fly” in Peter Pan, Jerome attempted the same performance, “from the top of Winsor’s toboggan slide with the aid of an umbrella and with disastrous results.” (James M. Wood, Out and About with Winsor French, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2011, 115.) The boys both survived, and were later cast in Cleveland Playhouse productions.

The 1910 census lists many of the Ambler Heights families with several children and several servants living in the homes. At 2163 Harcourt, the census lists an English couple, Frederick and Minnie Feltwell, as butler and maid, an Irish widow, Nellie McGough, as a maid, and a single German woman, Anna Bartz, as cook.

Kindergarten days were at Laurel School, which boys then attended as well as girls, and then to University where a bully two classes ahead made my life miserable. Lord, how I loathed that school. Fortunately, I was saved from it by the timely slump of one of father’s coal companies. I then went to Roxboro, a public school, which I very much enjoyed, especially after I fell in love with the enchanting little Shirley Harrison. Many were the days my sister and I walked home from school across the golf course, carrying our lunch boxes. One unhappy event: Margaret’s head was badly cut by a school swing, but Dr. Charles Brigg’s expert surgery left no scar.

“The House on Harcourt,” 35

The account of the time in Happy Times, written by Brendan Gill (presumably with input from Jerome), states that a chauffeur would drive Jerome to the public school, where a bully would attack him as he stepped from the car. “Jerome assumed this was the nature of the human condition and took his daily beating as bravely as possible, but the chauffeur was upset.” He recalled that the chauffeur tried to outwit the bully by dropping Jerome a block from school, and then the bully beat up the chauffeur.

Source: Brendan Gill and Jerome Zerbe, Happy Times (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1973), 13

Happy Times also reports that Jerome Sr., at age 58, celebrated his son’s birth by retiring. (From other descriptions it seems he was involved with the business until his death in the 1930s, but perhaps he had stepped down as president.) Jerome Sr., described as able but unambitious, spent his last 30 years playing bridge at the Union Club. As a result, the Zerbes were limited to being “well-fixed” rather than truly wealthy, like many of their Cleveland friends.

The 1952 article describes 1916:

After eleven happy years for us in the Harcourt house, a coal slump continued to such a degree that keeping the place was impractical. Mother found an unattractive but comfortable house on Norfolk Road, we sold our house and tearfully moved. That our new ugly duckling of a house should gain a reputation for hospitality I could foresee, but that was due entirely to Mother’s magical touch. We all faced a new life, which promised to be a good one.

Source: Jerome Zerbe Jr., “The House on Harcourt,” Curtain Call (Cleveland: Gruber Foundation, 1952), 36

Again, Happy Times tells a slightly different version of the story. Jerome was distressed when his mother said that she planned to but the ugliest house in Cleveland. He was relieved that their new home, [2575 Norfolk], was a lovely Queen Anne, furnished with fine French pieces.

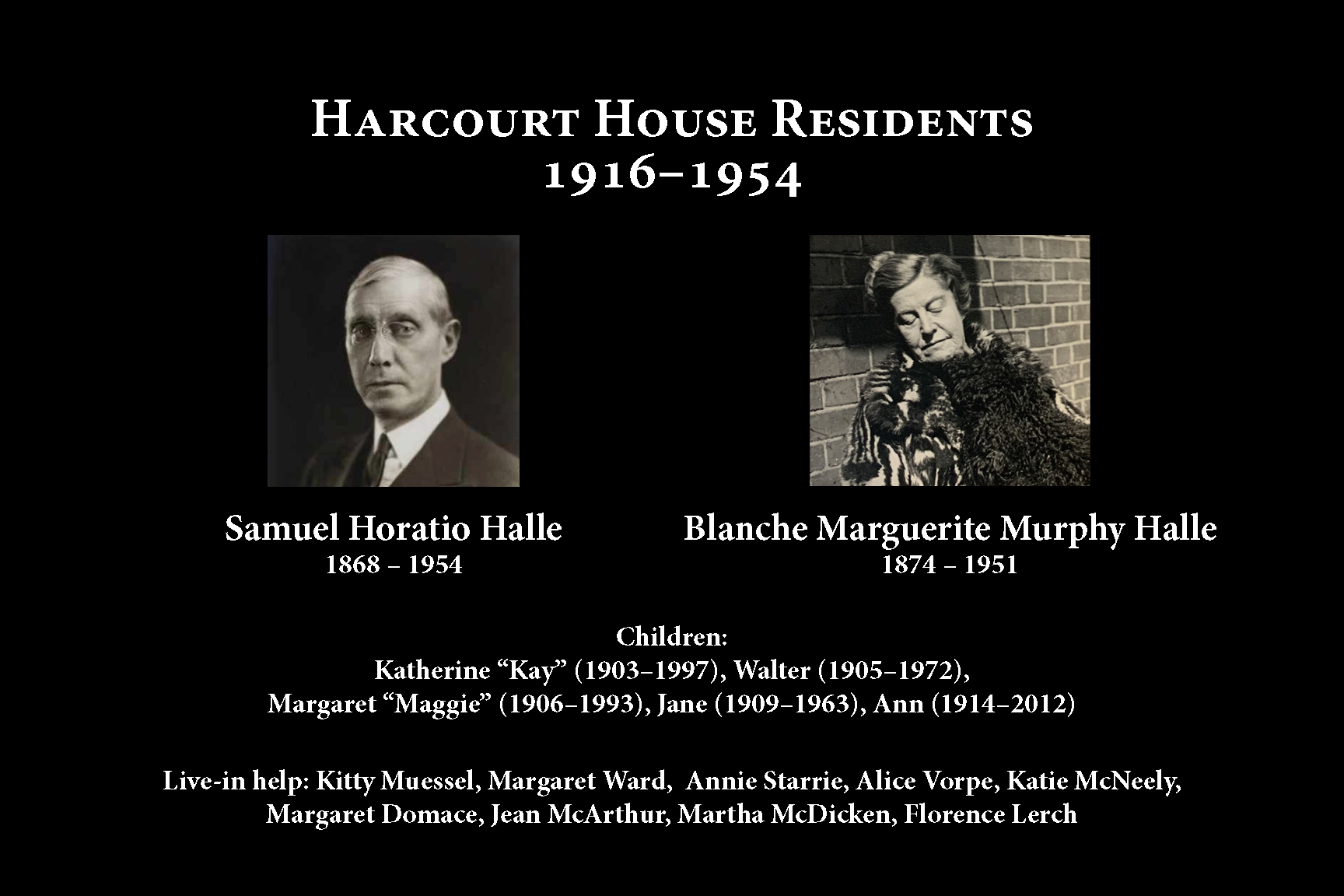

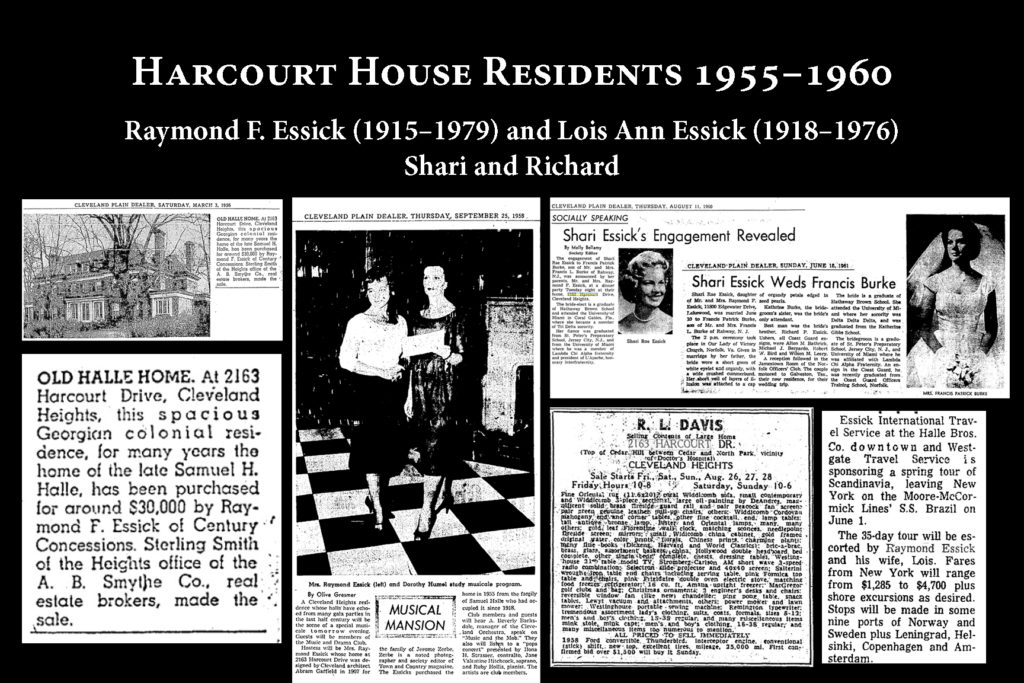

In 1916, the Zerbe House was sold to the Samuel Halle Family. The Zerbes may have sold a part of the property before this time, as the lot of J.B. Zerbe appears much larger in a 1912 map than in a map from 1927–1937.

Young Jerome and Margaret were 12 and 13 at the time of the move. Jerome mentioned the Halle children living nearby. They were across Cedar on Overlook. Margot and Jerome were 13 months apart in age, and the oldest Halle daughter, Kay, was between their two ages and Walter Halle was six months younger than Jerome Jr. Jerome Junior would continue to socialize with, and photograph, the Halle children as adults.

Times were apparently not so hard for the Zerbe family, as the 1920 census for the Zerbe family again lists live-in servants: a Georgia-born Black chauffeur, James Smith; a young white maid from Virginia, Anna Geda; and a widowed Swedish maid and her teenage daughter, Helda and Edith Hamilton.

Jerome closed “The House on Harcourt” article with

Now for many years our old house on Harcourt has been the home of the Samuel Halles, who bought it from us. Time has been kind to it; time and the loving care of people who have always cherished it. I, too, loved the house and I still do.

Jerome Zerbe Jr., “The House on Harcourt,” Curtain Call (Cleveland: Gruber Foundation, 1952). 36

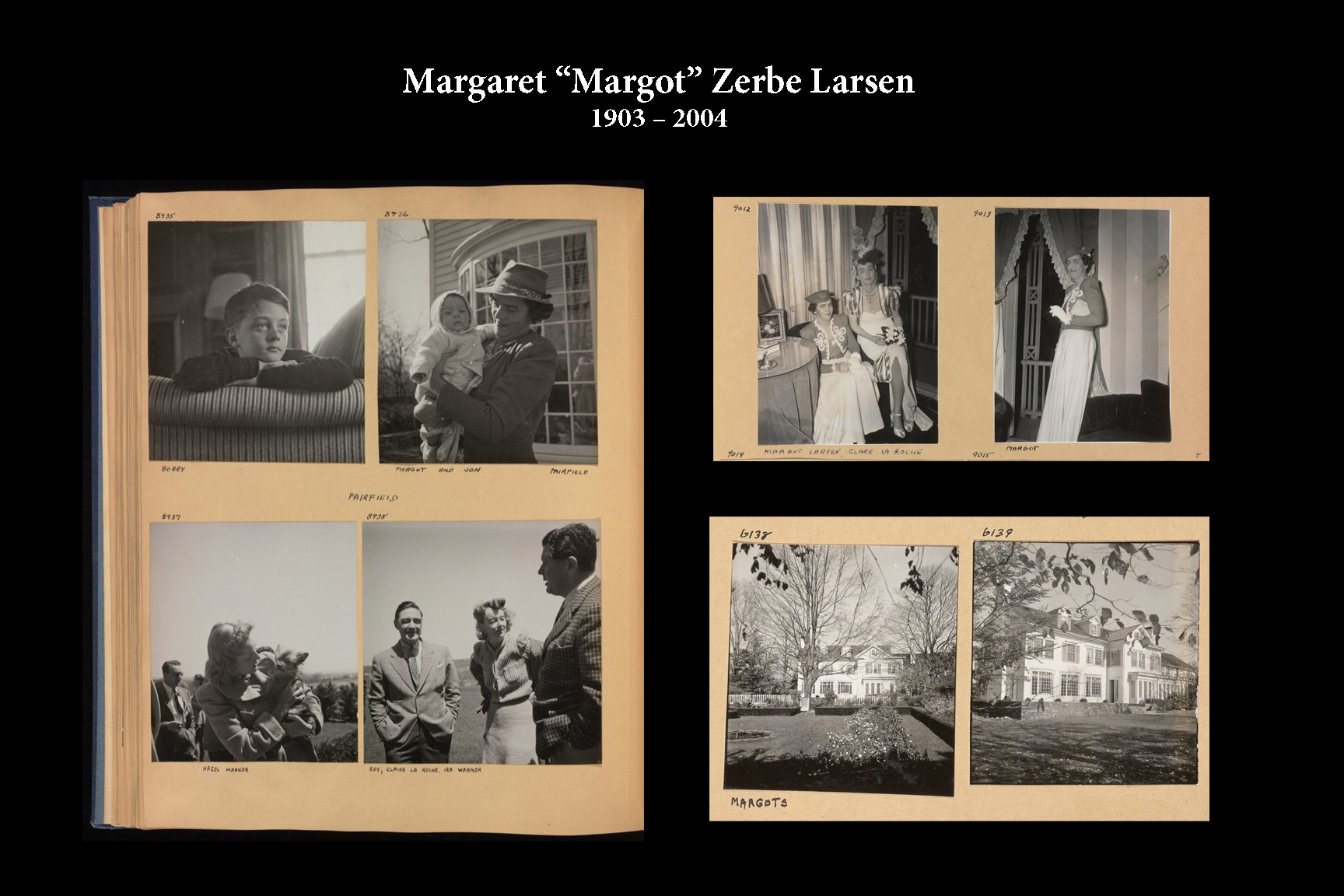

Margaret, known early as Maggie, attended Hathaway Brown School. Jerome renamed his sister Margot, because long before he reached his teens, “he liked things to sound stylish, and, if possible, French; he was a Francophile from the cradle.” (Happy Times, p.13)

Margot would marry Roy Larsen in 1927 and move to New York, then to a lovely home in Connecticut where they raised their four children: Anne, Robert, Christopher, and Jonathan. Margot had a deep interest in wildlife and conservation. She and Roy established the Margot and Roy Larsen Sanctuary of the Connecticut Audubon Society. They donated 513 acres to the Nantucket Conservation Foundation. Working under licensure from the Fish and Wildlife Service, Margot banded over 24,000 birds. She, Roy, and their children remained close to her brother throughout his life. He dedicated his 1976 book, Small Castles and Pavilions of Europe to Margot and Roy. She would live to 100 years of age.

At age 13, Jerome was going to Saturday classes at the Cleveland School of Art. Happy Times recounts that when he went to the Salisbury School in Connecticut, he most recalled his interests in drawing sketches of football captains and in photography. While at school, he became seriously ill with a tuberculous gland in his neck. Famed surgeon George Crile operated on him in Cleveland and recommended a year of rest to recuperate. The family spent 14 months touring Italy, Rhineland, and France. While the family stayed on the Riviera, Jerome spent the weekend with W. Somerset “Willie” Maugham.

Jerome enrolled in Yale in 1924, where he developed many social connections based on his ability to secure alcohol during prohibition and always knowing where the parties were. His knack as a social networker would serve him well in life. He graduated from Yale in the class of 1928.

Jerome’s papers and some of his 50,000 photographs and 150 scrapbooks are stored in the archives of Yale University library. (His archive contains 159 boxes in 28 lineal feet.) The Library held a 2019 exhibition of his work titled “Life of the Party: Jerome Zerbe and the Social Photograph.”

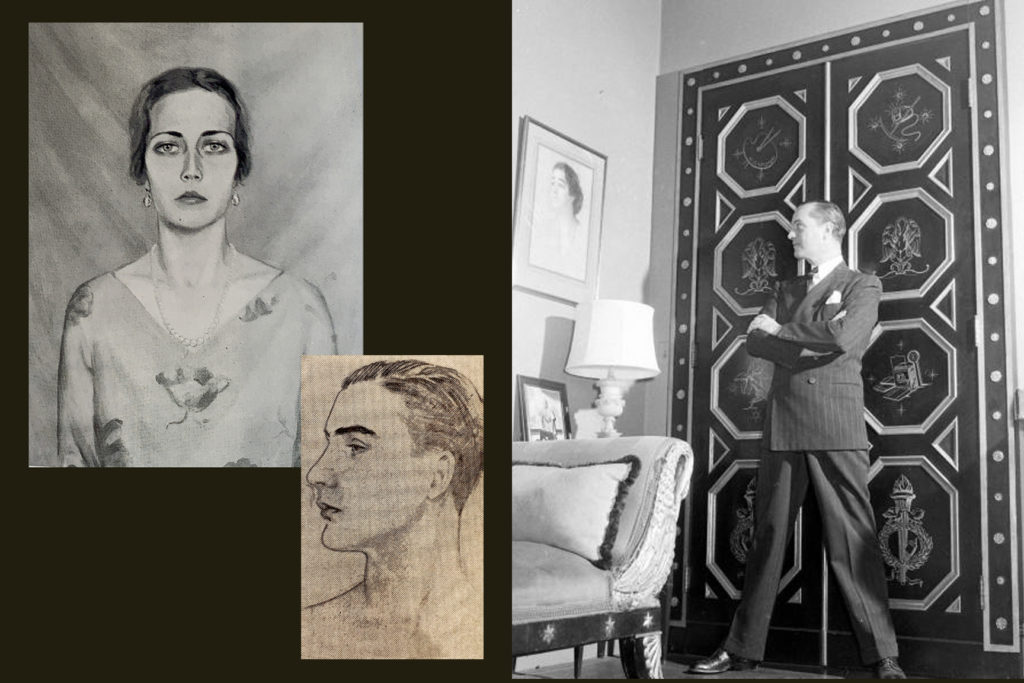

After graduation, Zerbe went to Hollywood with his half-sister’s niece, Princess Irma Odescalchi, planning to draw portraits of society figures. Instead, he was hired to draw movie figures Cecil B. De Mille, Norma Shearer, and Basil Rathbone. He also took a lot of photographs.

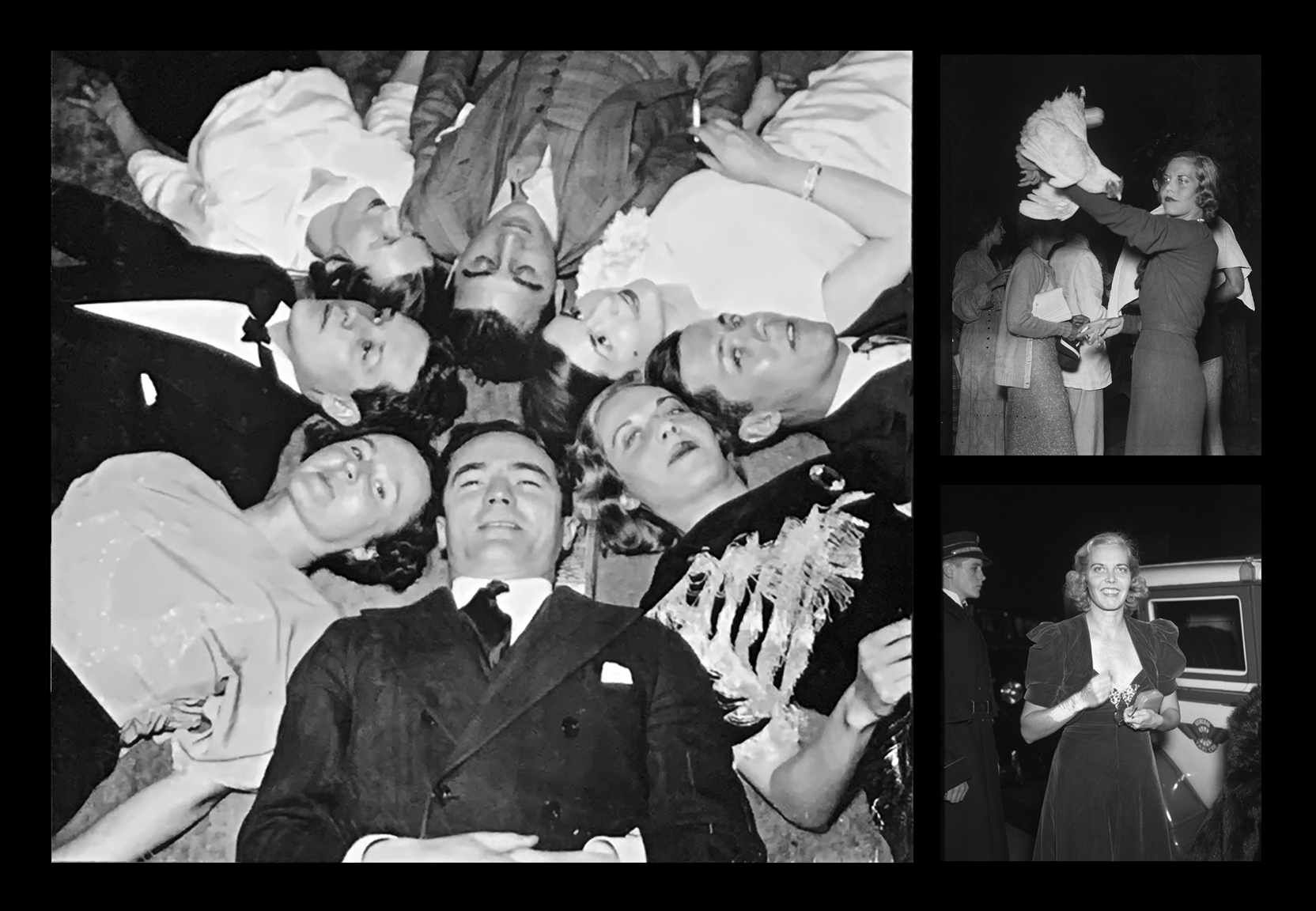

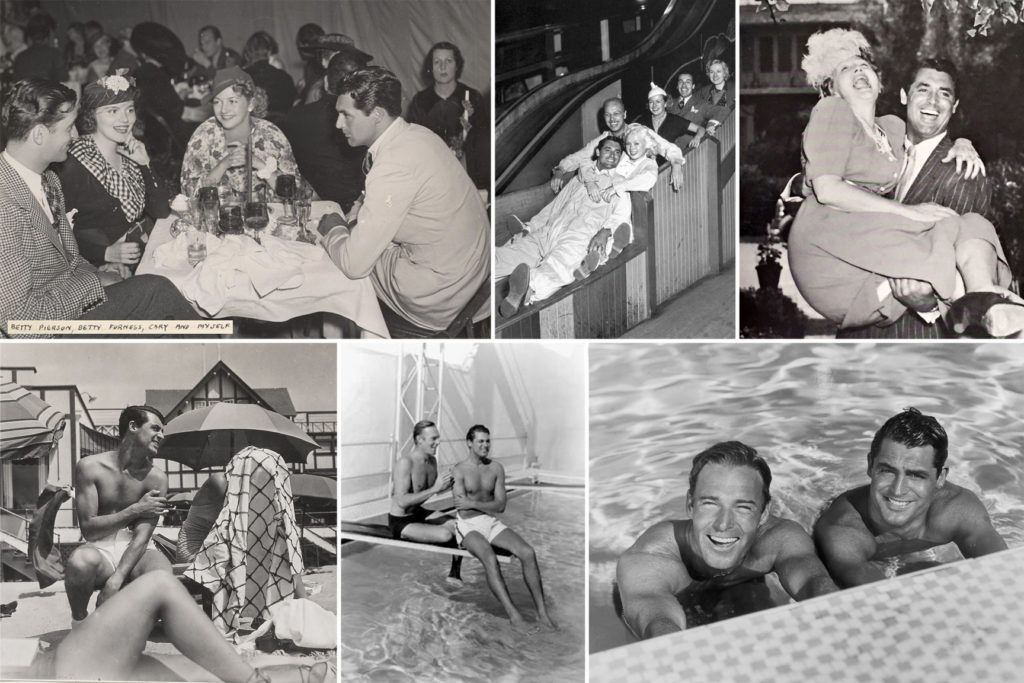

In Hollywood, he befriended acting newcomer Gary Cooper, who introduced him to others who became lifelong friends, including Cary Grant, Randolph Scott, Errol Flynn, and Hedda Hopper.

In 1929, Jerome went to Paris to study painting. He met art and society figures, and realized that he did not want to spend the necessary amount of time painting to achieve his goal of being the next John Singer Sargent. However, he decided he could happily combine his skill in photography with his love of party-giving and party-going.

With the arrival of the Great Depression, Jerry was called back to Cleveland to contribute, rather than spend an allowance in Paris. (It was said that even the family cook and chauffeur were feeling the pinch of hard times.) Margo’s husband was the first employee of Time magazine(he would later be vice president for 21 years), and was doing well.

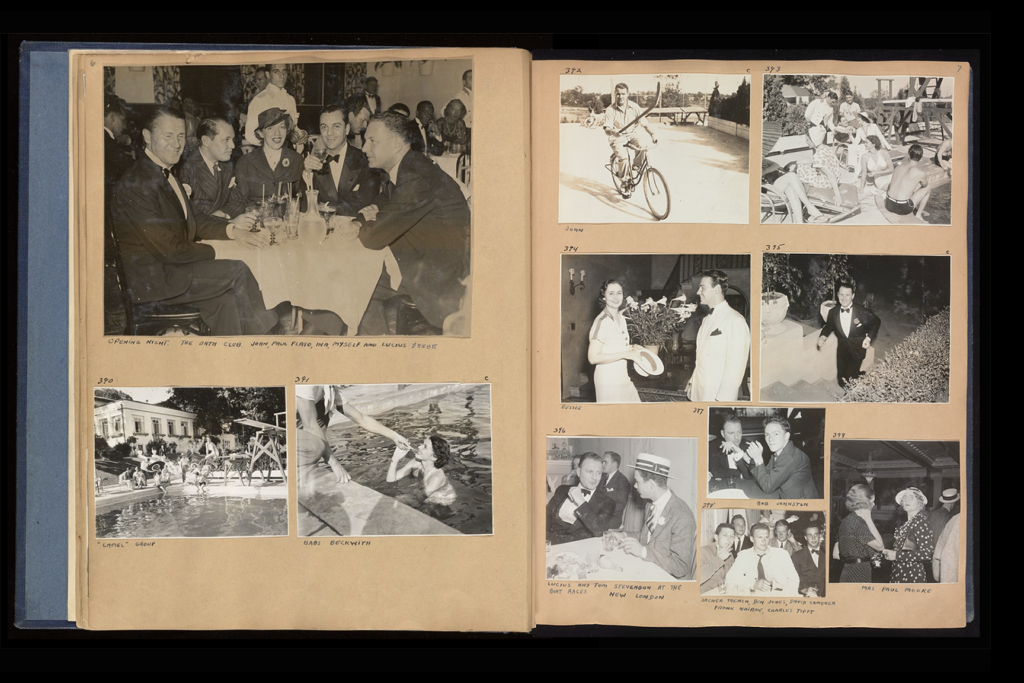

Jerry’s childhood friend and neighbor, Winsor French, offered him a job with a new magazine. Winsor had written for the Cleveland News, then Time Magazine in 1927. He moved from Cleveland to New York with Time, but returned to Cleveland after a short time with the idea to start a weekly magazine called Parade, as The New Yorker or Vanity Fair of Cleveland. He started the magazine with financial backing from W. Walter White, and hired Jerome as art director, to draw, write, and take photographs. The “stars” of Cleveland became his subjects.

At the time, a woman’s name was expected to appear in print only three times: at her birth, her marriage, and her death. Jerome, as part of the society that he sought to photograph, had full entrée into the best parties around the country. He convinced wealthy Clevelanders that publicity for their parties would improve the success of their charity balls and fundraisers. This was a new concept, and he was proved correct. That he was often the life of the party added to his welcome. Some of the Cleveland party-goers subjects were the younger Halles, who lived in the house on Harcourt Drive that he had lived in as a child.

As Jerome described the time in the Studs Terkel oral history,

My father allowed me an allowance of $300 a month. On that I went to Paris and started painting. Suddenly he wrote and said: no more money. And what does a painter do in the Depression with no money? I came back to America and was offered a job in Cleveland. Doing the menial tasks—but the time I was grateful of——art-directing a magazine called Parade. $35 a week. It was 1931. I thought, to goose up the magazine, I would take photographs at my own home. . . . I got photographs of Leslie Howard, Ethel Barrymore, these people. Billy Haines was a great star in those days. We published them in Parade. It was the first time what we call candid social photography was founded. I had known I’d start something. Town and Country asked me to various estates and I went over and photographed people I knew. They were all horrified at the thought and couldn’t wait for the pictures.

Studs Terkel, Hard Times (New York: Pantheon Books, 1970), 211-212

Although the Depression was in full-swing, the society parties continued. One of Jerome’s friends did consider the optics in planning her daughter’s debut: “I want to keep it simple,” she insisted, “even if it costs me a million.” (Happy Times, p.17)

Jerome became the first, and perhaps the only, true society photographer, because he was of the society that he was photographing.

In 1933, as Parade magazine was fading, Jerome Senior, shortly before he died, offered the coal company presidency to Jerome Junior at $12,000 a year. He considered it—until he visited a coal mine in Cadiz, Ohio, on the West Virginia border.

Later Jerome would become friends with Clark Gable, who worked in the Cadiz mine in his youth. The two bonded over their mutual hatred of mines and mine towns — “They lacked charm,” Jerome said, in understatement. (Happy Times, p.12)

While Jerome turned down $12,000/year to work for the coal company, he jumped at the opportunity to make less than $2,000/year at Town & Country. Nonetheless, in later years he seemed unsympathetic to his father’s stepping away from daily operations of the coal business, saying in a 1952 newspaper interview that he took up photography “because my father was a disappointment to me.”

Jerome continued in Hard Times:

After my father died, and no money, I sold my library books to the Cleveland Museum and the Cleveland Art Library. With that money, I came to New and started out. Town and Country had guaranteed me $150, which seemed a lot. This was ’33. One day, a gal from Chicago called me up and asked if I would have lunch with John Roy and herself at the Rainbow Room. So we lunched, and he said: ‘Jerome, it’s extraordinary how many people you know in New York. Would you like to come work at the Rainbow Room? I’ll pay you $75 a week, if you come, take photographs, and send them to the papers, and you will have no expenses.’ The Rainbow Room, here at the Rockefeller Center. This is 1935. The famous room at the top. So twice a week, I would give a party and photograph my guests, all of whom were delighted to be photographed. The first night of this, I was so pleased, because I had been so poor. I still had my beautifully tailored clothes from London. I still had the accoutrements of money, but I had no money. You know? It was cardboard for my shirt and shoes when they got old. So I went to El Morocco to celebrate this job. John Perona said, ‘I’ll take you the other three nights.’ This made $150 a week. Then he said, “Jerry, cut out that Rainbow Room racket. They’re getting more publicity than I am. I will pay you the same amount, if you leave your camera here. Then you won’t have taxi fare, you won’t have problems. So I went to work for John Perona. From 1935 to 1939, I worked at the El Morocco. He’s a legend. He’s dead now. He and I fought all the time. And I was always quitting. I adored him. I invented this thing that became a pain in the neck to most people. I took photos of fashionable people, and sent them to the papers. . . The social set did not go to the Rainbow Room or the El Morocco, until I invented this funny, silly thing: taking photographs of people. The minute the photographs appeared, they came.

Terkel, Hard Times, 211-212

At the end of the Hard Times interview, which was about the Great Depression, Jerome said,

The Thirties was a glamorous glittering moment.

He was more circumspect in Happy Times, published three years later. Brendan Gill wrote,

Zerbe has always been puzzled by the fact that throughout the grim period of the Depression the sorely beset poor and even the unemployed seemed to take pleasure in pictures of the rich squandering their unearned incomes upon frivolity. ‘I’d have expected my pictures to make people furious,’ he has said. ‘They had the opposite effect. My friends and I were all more or less Marie Antoinettes in our attitudes, but instead of having our heads chopped off, we were applauded.’

Gill, Happy Times, 18

The zebra-striped banquettes in El Morocco could not have been better designed for photographs, as they signified the club better than any strategically-placed, branded ashtray could ever hope to do. Jerome sent the photos to newspapers, first to the seven newspapers and three press associations in New York City eager for the photos, then more broadly. Club goers would stand in long lines hoping to get in and be photographed.

Due to Jerome’s many connections, aristocrats and stars were also frequenting the club. For five years, Jerome spent most nights, from 9:00pm to 4:00am, eating, drinking, and taking thousands of photographs.

During this time, Jerome was the romantic partner to author and society columnist Lucius Beebe. Beebe referred to Zerbe so regularly in his column that rival columnist Walter Winchell quipped that Beebe’s column should be renamed, “Jerome Never Looked Lovelier.” Beebe wrote the introduction for Jerome’s first published book, People on Parade, in 1934. Jerome would soon publish El Morocco Family Album (1937) and Bachelor (1937).

Meanwhile, Jerome would continue to visit Hollywood. Attending parties with so many beautiful people, Jerome would take his camera along. At the time, published photographs of stars were often posed and lifeless. Jerome’s more candid photos showed a glamorous lifestyle that the public loved seeing. He only shared flattering photos, so the stars enjoyed the publicity.

It was rumored that Zerbe was romantically involved with Cary Grant. By 1932, Cary Grant and Randolph Scott were living together as famous Hollywood bachelors. A 2020 biography of Cary Grant by Mark Glancy (Cary Grant, the Making of a Hollywood Legend) debates whether Grant and Scott’s relationship was secretly gay, or if Zerbe’s photos influenced that opinion and the men were actually secretly straight.

A biography of Jerome’s close friend Winsor French states that “Winsor’s datebook substantiates Zerbe’s boast that he and Grant were lovers during the summer of 1935.” (James M. Wood, Out and About with Winsor French, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2011, 80.) As a cover, newspapers were fed a story of a romance between Grant and actress Betty Furness, supposedly substantiating those rumors with photos of the couple taken by Jerome Zerbe.

Grant and Scott would later marry women. Zerbe never married.

Only a true friend helps you move. Jerome helped Hedda Hopper move by photographing Cary Grant carrying boxes, and carrying Hedda

across the threshold of her new home. Bottom two photos show Randolph Scott with Cary Grant.

While Jerome would always insist that he loved a good party, it must be noted that he took many thousands of photos in the pre-digital age when taking, developing, and sorting photos was a lot of work.

Jerome worked at the New York World’s Fair in 1939 at the Brazilian Pavilion. In 1942, during World War II, Jerome enlisted in the Navy.

Little in Zerbe’s years in the restaurants, nightclubs, and private houses of Manhattan prepared him for life in the steaming below decks of a troopship. Nonetheless, he went on smiling, and the evidence is that nearly everyone smiled back.

Gill, Happy Times, p. 113

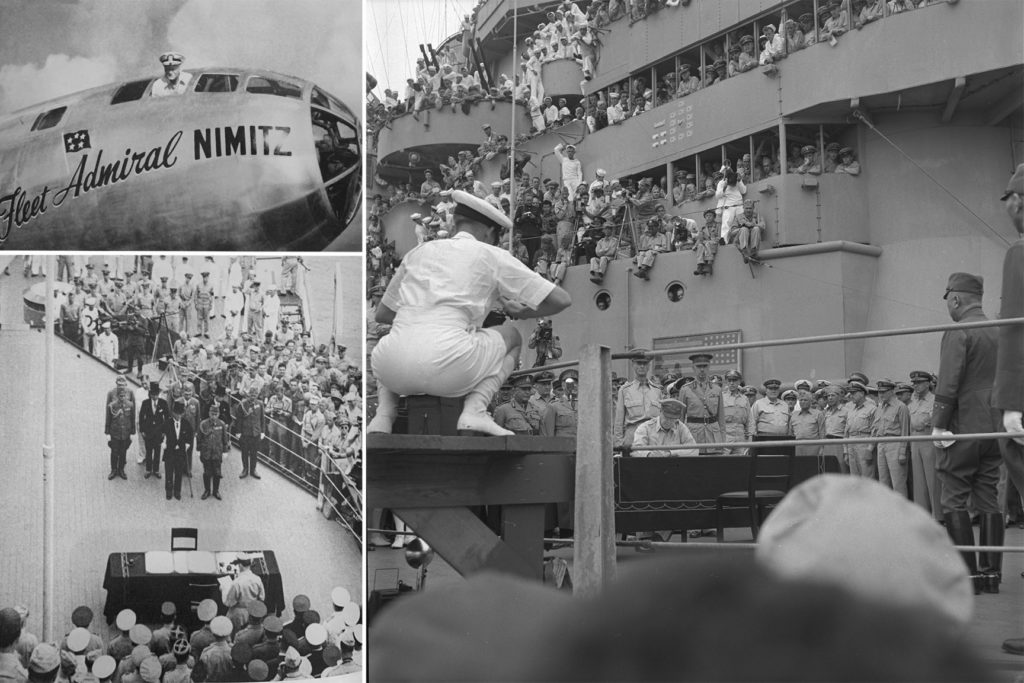

Rather than seeking an officer’s commission, he signed on as a chief photographer’s mate. After being spotted by an old friend, writer Robert Sherwood, he became the official photographer for Admiral Nimitz. He travelled with the stars that entertained the troops. He took a photograph of Ernie Pyle, Pulitzer-prize winning photographer and journalist, a week before he was killed.

He also photographed Franklin Roosevelt Jr. during that time. Perhaps that is when they first became friends. Jerome said in his Hard Times oral history interview,

John Roosevelt and young Franklin were great friends of mine. I photographed them in my apartment. We never did discuss the old man, ever. Well, I never did like politics…”

Terkel, Hard Times, p.215

Like his friend Kay Halle, Jerome became friends with the Roosevelt sons. Unlike Kay, he distinctly disliked FDR. He said, however, that “Eleanor was a great woman.”

Jerome photographed the signing of the Japanese surrender papers aboard the U.S.S. Missouri in September 1945. His maternal uncle, Lieutenant General Robert Eichelberger, was also there, as General MacArthur’s aide. After the surrender, Jerome and Uncle Bob travelled in Japan on a two-week holiday. Jerome was awarded a Bronze Star for meritorious service.

After the war, Jerome resumed photographing Café Society, traveling throughout the world photographing celebrity events. Jerome worked for Hearst newspapers, and wrote a weekly column for the Sunday Mirror for over a decade. Beginning in 1949, he was society editor for Town & Country magazine for 25 years.

The above photo of Oona O’Neill, aspiring actress and teenage daughter of playwright Eugene O’Neill, testifies to how comfortable subjects were with Zerbe. (About a year later, the month after Oona turned eighteen, she would become the fourth and final wife of Charlie Chaplin, and bear him eight children.) While the photo shoot was arranged for Jergen’s Lotion, most of the photos were taken for fun.

Jerome’s success allowed him to indulge in his love of French homes, albeit in Essex, Connecticut. He designed, had built, and lived in a French-style estate on the Connecticut River. He would regularly invite as many as fifty people over, including Joan Crawford, Joan Fontaine, and his dear friend Hedda Hopper, and cook them Sunday brunch.

There, he photographed Katharine Hepburn. As he described,

Once I asked Katharine Hepburn to come up from her place at Fenwick, a few miles away, and pose for some fashion photos for me. She arrived with a picnic hamper full of food and wine for the two of us. I snapped her just as she came to the door. How beautiful she was and how beautiful she is!

Gill, Happy Times, p.26

Happy Times contains hundreds of celebrity photographs from Jerome Zerbe’s archive of 50,000, with commentary by New Yorker writer Brendan Gill. Casual photos include Howard Hughes, Gloria Swanson, Noel Coward, Doris Duke, Gypsy Rose Lee, Tennessee Williams, Jean Harlow, Gary Cooper, Humphrey Bogart, Kirk Douglas, Clark Gable, Greta Garbo, Maria Callas, Cary Grant, Carole Lombard, Grace Kelly, Ingrid Bergman, Gene Tierney, Buster Keaton, Thomas Wolfe, Marilyn Monroe, and many others.

Over time, Jerome became more interested in architectural photography. He had expanded his photographic repertoire to estates and country homes in Europe, and published two books of those photos: Les Pavillons: French Pavilions of the Eighteenth Century and Small Castles and Pavilions of Europe. (His love of houses surely began at 2163 Harcourt Drive.)

Jerome was 69 when he collaborated with Brendan Gill on the Happy Times book. Gill writes that Zerbe was certain, and not distressed, that he would not live beyond another year or two.

It’s true that I wouldn’t have liked being among the first to leave the party, but I’m relieved now not to be among the last. . . . Much nicer to go when one is still capable of saying a proper goodbye.

He went on to explain that his doctor has warned him he drinks too much, and,

…some of my ancestors hung on into the high nineties, but their habits were, shall we say, different from mine. They thought night was for sleep and day for work, and I suppose they thought play was going to happen to them in heaven. I think night is for play and day for sleep, and I manage to fit my work into the interstices. I’m certainly not going to live on and on just to please my doctor. Being a cheerful person by nature, I find I am able to think quite cheerful thoughts about my own extinction. . . . To give my doctor some satisfaction, I take care to drink as little as possible until dark. One of the nice things about winter in New York is how early it gets dark.

Gill, Happy Times, p.12

Jerome Zerbe lived another 15 years, to age 84.

In 1916, the Halle family moved from Overlook Drive across Cedar to Ambler Heights. Many Cleveland mansions are called by the names of their original owners, but as the Zerbes lived at 2163 Harcourt Drive for 10 years, and the Halles lived in the home for almost four decades, the house was called the Zerbe/Halle house or, more often, the Halle house.

Halle family history

Aaron Halle had been the first of the Bavarian Halles to make his way to America, in 1840. He headed to a German-speaking community in Albany, NY. His friends there explained that a trip through the Erie Canal could take him to a greater opportunities, so he worked two years to afford passage to Cleveland. The Halle family history doesn’t mention what opportunities were better in Cleveland, but it is interesting to note that Aaron would be arriving in 1842, just three years after Moses Alsbacher, also from Bavaria, arrived in Cleveland and established the first permanent Jewish community in the city.

Aaron opened a grocery store and, after two years, saved enough money to send for his cousin Manuel. Fourteen-year-old Manuel was robbed during the ocean passage, and worked at menial jobs to get to Cleveland. Throughout his life, he recalled with distaste the terrible conditions in a cigar factory. Two years after arrival, Manuel sent money to younger brother, Moses, now fourteen, who also worked his way through the canal, arriving in Cleveland in 1848. Four more family members would follow.

In 1856, Manuel and Moses worked as clerks in the City Mill Store with young John D. Rockefeller. Manuel began investing in oil refineries, but sold his shares of Standard Oil back to his old friend Rockefeller because of the lack of safe-work practices. (Perhaps recalling the cigar factory, he was intensely affected by the horrific death of a worker in the refinery, and the refusal to invest in guard rails. He boycotted Standard oil investments.)

After Manuel married Augusta “Gusty” Weil, and then Moses married her sister Rebecca, the brothers started M. and M. Halle Co., selling men’s furnishings and notions. Manuel and Gusty had children Ida, Dora, Della, William, and Eugene. Next door, Moses and Rebecca had two young sons, Salmon Portland and Samuel Horatio. Sal was five, and Sam just three, when Rebecca died of tuberculosis. Gusty mothered the boys until Moses married opera singer Rosa Lowentritt a few years later. Moses and Rosa had daughters Jessie and Minnie.

During high school years, Sam was in poor health and spent winters in California in hope it would help cure his lung ailments. It seemed to have done so. The time also enhanced Sam’s sense of adventure and love of the outdoors.

Returning to Cleveland, Sam, or S.H., would often talk with Sal, or S.P., about starting their own business. They had been to Marshall Field’s department store in Chicago, and dreamed of such a place of their own. Moses gave them funds to invest in their futures, which they combined to have $10,000 to purchase a business.

Halle Bros.

In 1891, Salmon and Samuel bought Captain T.S. Paddock’s store, at 221 Superior Street near Public Square in Cleveland, from his estate. The inventory included hats, caps, furs, gloves, and umbrellas. Halle Brothers was born. It was hard work, and they needed a loan from their father, Moses, to withstand losses of the first year, but success would follow.

The store began as a furrier and hat repair shop. In the first six months, a lovely young Southern woman named Carrie Moss came in for mending, repeatedly. She and Sal married in 1893.

Married Sal noticed his brother Sam would comment on the sales staff: “Irish beauty, there’s nothing like it.” One particular beauty was Blanche Murphy. Blanche’s Irish-born father, Timothy, was a successful tailor, but had died when Blanche, one of eight children, was just ten years old. Her Canadian-born mother, Mary, went to work as a dressmaker. (James M. Wood, Halle’s: Memoirs of a Family Department Store, Cleveland: Geranium Press, 1987, 40)

Once Sam was introduced to Blanche, in 1896, he asked her out for a carriage ride around Wade Park. He quickly proposed; she took her time accepting. Her Irish Catholic mother would have preferred a different partner, and on this Sam’s Jewish family would likely have agreed. Nonetheless, in July 1901, they began a successful interfaith marriage.

Near the end of Blanche’s life, one of her nephews, a priest, visited her hospital room hoping to welcome her back into the fold. She exclaimed, “What are you doing here?” She later told her youngest daughter that she had no regrets. (Wood, Halle’s, 182)

While Sam and Blanche were courting, the store had begun carrying women coats, then more clothing. They developed a regional mail-order business. In 1897, they were well known enough for their women’s clothing that President McKinley’s wife, Ida, bought a ready-made blue serge dress, jacket, and sealskin coat from the store for her husband’s inauguration. The items included sewn in tags labelled “The Halle Bros. Co.”

Halle Bros. expanded their merchandise and moved into larger quarters in the Nottingham Building in 1898, incorporated in 1902, then moved again into the entire 10-story Pope Building, at a rent of $1 million/year in 1908. They would nearly double that large Euclid Avenue space with a new building, finished in 1914. The building was designed by Henry Bacon, who was the architect for the Lincoln Memorial in the same year the Halle building was finished.

Sam and Blanche’s family grew along with the store. They would have five children born 1903 to 1914, and give each child the middle name Murphy. The family lived in Cleveland Heights, on Overlook Drive.

Harcourt Drive

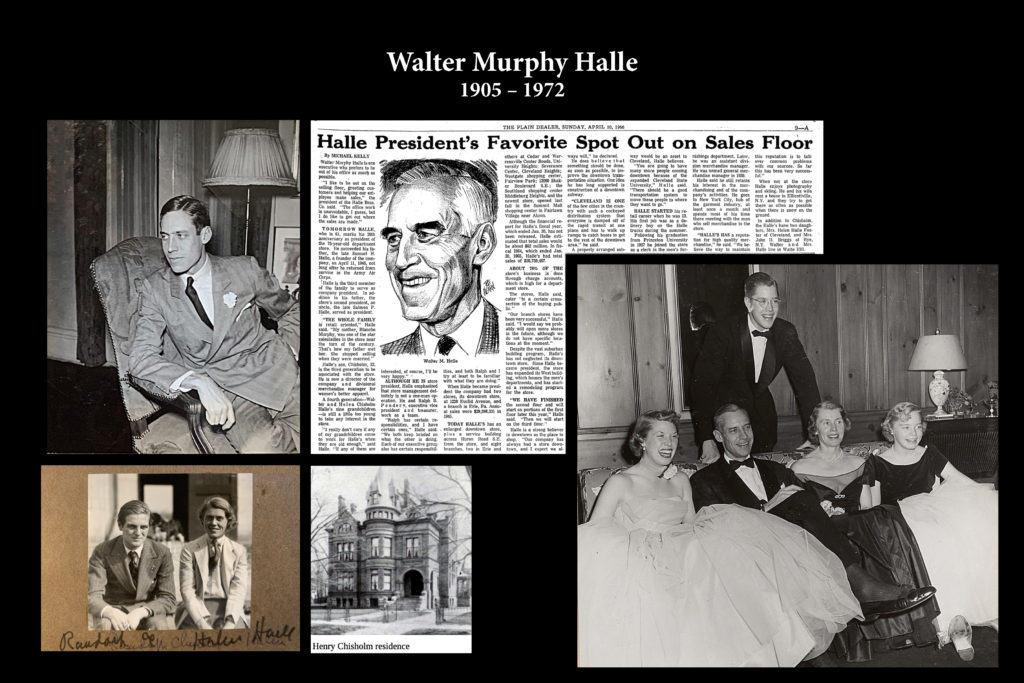

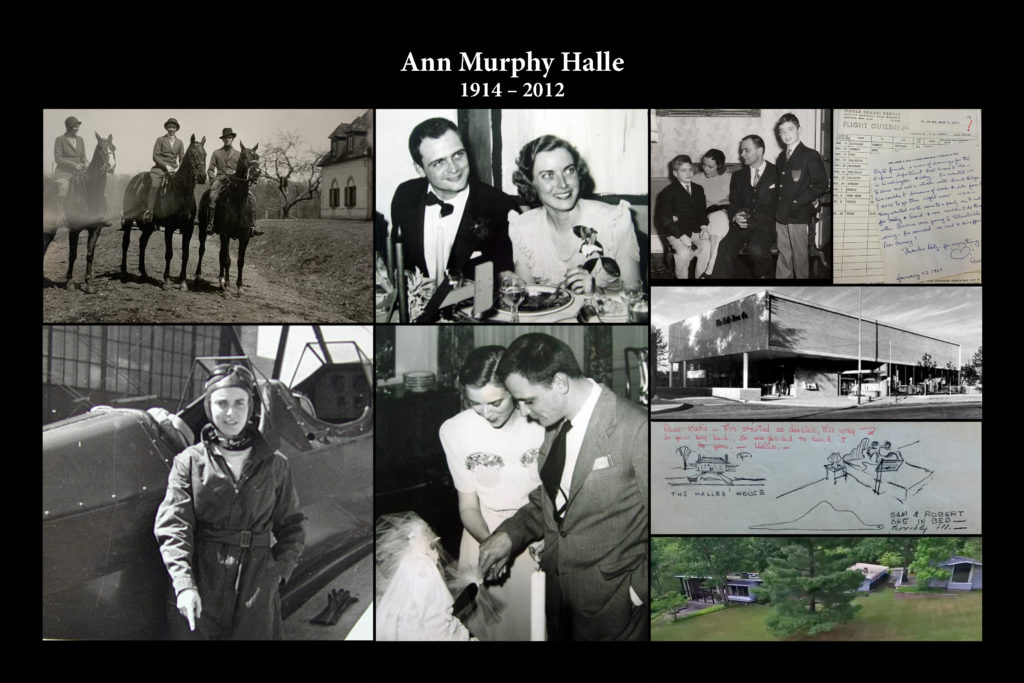

During the summer of 1916, the year that the Halle family moved into 2163 Harcourt Drive, Kay was 12 and Walter was 11; Maggie had just turned 10, Jane was 7, and youngest child Ann had just had her second birthday.

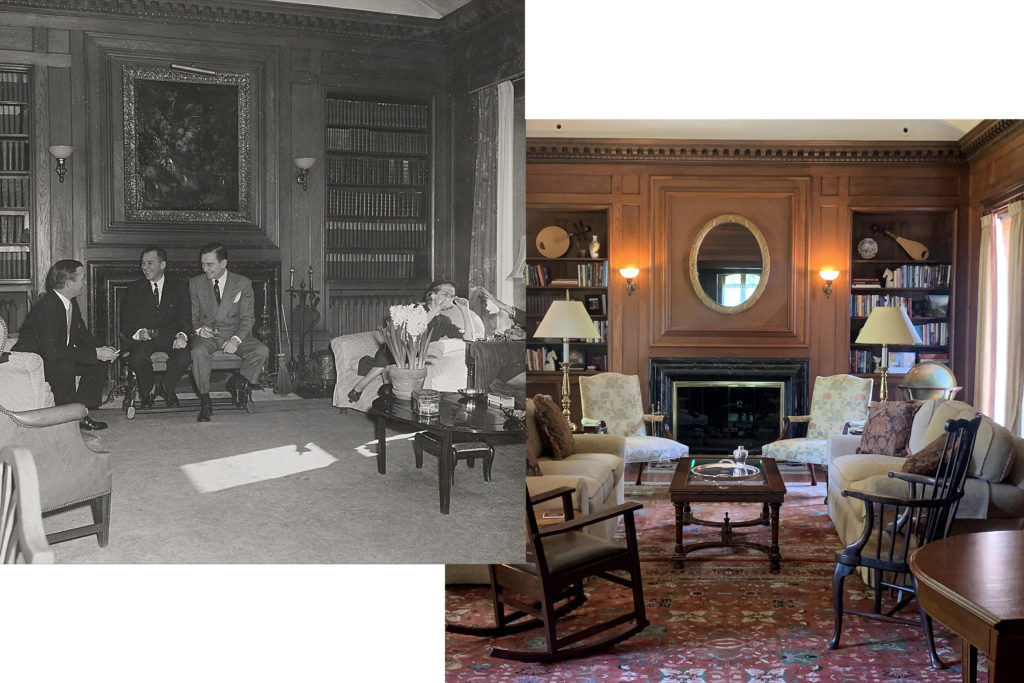

The family hired Abram Garfield to design a library to be added on to the back of the house.

The Help

Sam and Blanche had help with the large house and the children. The 1910 census listed four servants at the family’s Overlook Drive house, including 42-year-old cook Katherine “Kitty” Muessel.

Kitty, born in Dublin, would move into the Harcourt Drive home with the family and remain living there until her death, at age 77, in December of 1943. (Kitty was listed as either divorced or widowed in various census. She had been working for the Halles for about twenty years when her husband—perhaps still back in Ireland—actually died.)

In the 1920 census, Kitty was joined at Harcourt by two maids, Irish Margaret Ward, 27, and Annie Starrie, 24, of Austrian descent. Swiss governess Alice Vorpe, 30, would also be living in the home.

In the 1930 census, Kitty was joined by upstairs maid Katie McNeely, 26, and Margaret Domace, 33, of German descent. Kitty and Katie were both listed as being born in the “Free State of Ireland.” (Samuel Halle’s father’s birth was listed in the census as Germany in 1910, as Bavaria in 1920, and as Germany again in 1930.)

In the 1940 census, Kitty was still cooking for the family. Scottish Jean McArthur, 52, was listed as waitress, and Canadian Martha McDicken, 32, was listed as maid.

In the 1950 census, after Kitty died, Sam and Blanche were 81 and 76, and had just two workers. Scottish Jean McArthur was still with them at age 68, and was joined by Florence Lerch, a 52-year-old widow from Ohio, as both cook and maid.

Ambler Heights neighbors

Ambler Heights was continuing to grow. Four years, prior to the Halles’s 1916 move to the neighborhood, there were 31 houses; four years after their arrival there were about 56. By 1927, the neighborhood would be substantially complete. Prominent early families included those of Dennis Upson, President of the Upson Nut Company; George Hascall, President of Hascall Paint Company; Alva Bradley, Chairman of the Cleveland Builders and Supply Company; Edward Brown and Ernest Brown of the Brown Brothers Stores; A. V. Root and S. K. Root of The Root-McBride Company; Benjamin Bourne, President of the Bourne-Fuller Company; George Canfield, President of the Canfield Oil Company; Joseph O. Eaton, Chairman of the Eaton Axle and Spring Company; Amos Barron, President of the Amos Barron Company; Charles Cassingham, President of the Cassingham Coal Company, and, of course, the family of Samuel Halle of Halle Brothers Department Stores. (Source: Ambler Heights historic district application)

The house at 1801 Chestnut Drive is particularly notable. It was designed by Meade and Hamilton for Warren Bicknell, president of Cleveland Construction Company, and his wife, Kate Hanna Bicknell. The family moved from their 2323 Coventry Road home in 1920. The Bicknell children and Halle children were acquainted long before they became close neighbors, as Kay Halle’s papers contain a photo of the children together in 1910.

The Bicknell Mansion was purchased by the Baptist Home of Northern Ohio in 1939, to be used for senior living. The former master suite and the third-floor ballroom were converted into apartments, and a large addition was added. The community was renamed Judson Park in 1972 ,in honor of American Baptist missionary Adoniram Judson, and a 10-story tower was added in 1974.

Summers at the Farm

The Halle family spent summers at the family farm they bought in 1912. Hallefarm was in Kirtland. Maude Doolittle, a school teacher from Massachusetts, cared for the children and tutored them on nature “including the names and personal habits of hundreds of migratory birds who summered with the Halle family in Penitentiary Glen on Hallefarm. (During the winter, Miss Doolittle tutored Rose and Joseph P. Kennedy’s children. )” Ann Little’s obituary, 2012

The Halle and Kennedy families would later become friends, but it seems they were not yet acquainted during the days they shared Miss Doolittle. In the 1970s, the Halle heirs would donate Hallefarm. It is now Penitentiary Glen Reservation of the MetroParks system.

Salmon Halle retires

Salmon Halle’s lifelong goal had been to retire, as his father had done, as a rich man at age 50. World War delayed his plans, but in 1921 he insisted that his brother buy him out of the business. Samuel, age 52, was thinking of growth and expansion. He was still “fascinated by a department store’s power to change lives and nourish a city.” (Halle’s, p.16)

Salmon retired to pursue other interests and build a house in Shaker Heights. Samuel became president. He began opening branch stores in 1929. A new downtown building was built beginning in 1947. A Shaker Square branch opened in a new building in 1948. Sam continue to be involved in the store for the rest of his life. Samuel became board chair after he turned over the presidency to his son, Walter, after Walter returned from World War I. Walter remained president until 1966, when his son, Chisholm, succeeded him.

Youngest child Ann recalled the store as a family business. As described in Ann’s obituary, ehe store was closed on weekends, and she enjoyed visiting the

...ten-story, white terra cotta building on the triangle formed by Euclid Avenue and Huron Road in Playhouse Square. While her father worked in his office on the seventh floor, Ann busied herself operating an elevator in the dark, empty store––the beginning of what would be a lifetime love affair with her extended family of store employees.

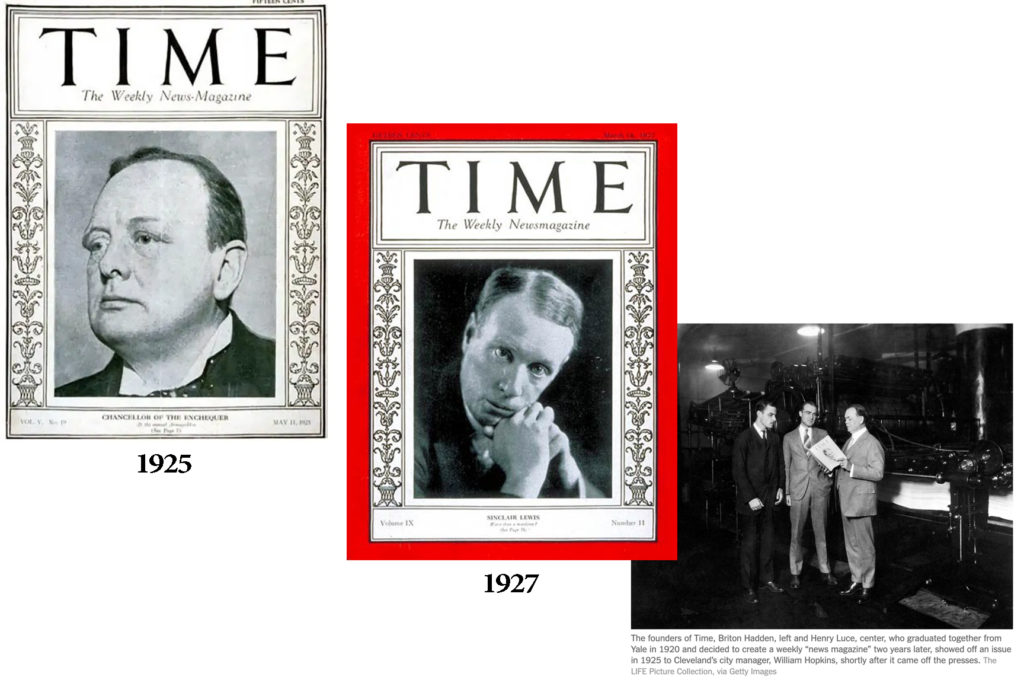

Time Magazine

The Halle family remembered Briton Hadden, Henry Luce, Roy Larsen, and John Martin trying to raise money for Time magazine in the Harcourt living room, and planning early issues of the magazine at the Halle farm in Kirtland. The magazine’s first issue had been printed two years earlier in New York.

Briton Hadden (1898–1929) and Henry Luce (1898–1967) were friends and classmates in Hotchkiss boarding school in Connecticut, and at Yale, Class of 1920, where they were the chairman and managing editor of the Yale Daily News. After graduation they were regularly talking together on the concept of a weekly newsmagazine.

In 1922, the two twenty-three-year-olds had been working together for a few months at The Baltimore News when they quit to work full-time on a magazine they initially planned to call Facts. Later that same year, they joined with a few-years-older Yale grad, Robert Livingston Johnson, and another Yale classmate to incorporate Time Inc.

Time magazine’s first edition was published on March 3, 1923. It was the first news magazine to be printed weekly in U.S.

Roy Edward Larsen (1899–1979) was hired in 1923 as the circulation manager. He was son of a newspaper man and a recent Harvard graduate who, as the business manager of the Harvard Advocate, brought that newspaper to profitability. By 1924, he was using the new and expanding radio business to attract readers.

The magazine was still losing money in 1925. Penton Publishing in Cleveland promised better prices on printing, and Cleveland’s location made national shipping faster. Luce wanted to move, butt Hadden didn’t. Larsen, with an eye of profit, broke the tie. Once in Cleveland, Luce and his wife lived quietly in Cleveland Heights, while Hadden moved to a downtown apartment and became friends with Jerome Zerbe and Winsor French, who were also close friends of the Halles. He dated Margo Zerbe. (After they broke up, she began to date Roy Larsen.)

By 1927, the magazine’s circulation was 175,000, finances were stable. Henry and Lila Luce went on vacation to Europe, and Britton Hadden moved Time magazine back to Manhattan.

Briton Hadden died tragically young in 1929, and Roy Larsen was named a Time Inc. director and a Time Inc. vice-president. He purchased 550 shares of Time Inc., becoming the second-largest shareholder. (One of the initial incorporators, Robert Johnson, who served as vice president and advertising director, was apparently much less involved. He took a leave from the company for another project, and left completely in 1938. He became president of Temple University in 1941.)

Roy Larsen became second only to Henry Luce in the further development of Time , and was referred to as Luce’s right-hand man. He worked at Time for 56 years, as circulation manager, then general manager, and finally president for many years, as Luce went on the found other magazines. He was Time Inc.’s vice-chairman of the board until the middle of 1979. (The 80-year-old was the only Time employee given an exemption from the policy of mandatory retirement at age 65. He would die six months after his retirement.)

There were at least two lasting legacies from Cleveland:

1) The iconic red border on the cover began during the Cleveland days.

2) In June of 1927, after dating six months and before moving back to New York, Roy Larsen married former Harcourt House resident Margot Zerbe.

The Churchills

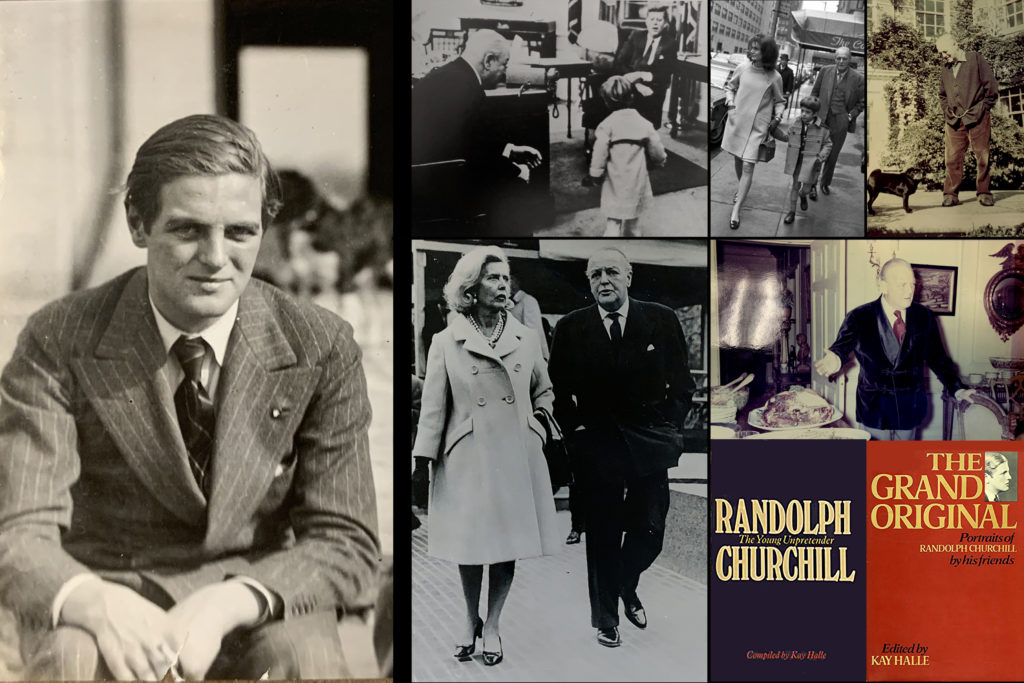

Randolph Churchill (1911–1968) was on a lecture tour of the United States that began in October 1930. As described by Kay Halle, four decades later:

He was then nineteen and of striking, Greek beauty. His virtuosity as a debater in the Oxford Union had attracted the notice of an American lecture bureau, who had signed him up for this, his first lecture tour of the United States.

Kay Halle, The Grand Original (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1971), 2

He met Kay Halle, nearly eight years his senior, while on tour. According to Kay:

I met Randolph at a wedding reception in Cleveland, Ohio. It would perhaps be more accurate to say I was commandeered into Randolph’s presence by his bewildered host, who had been firmly directed to bring me to him, without my escort, to their table. After the introductions, Randolph’s opening gambit was to inform me that I would shortly accompany him and his host to Little Mountain, in the country, for a raccoon hunt that had been arranged for him later that evening. If I refused, he too would decline to go. As I was dining that evening in honour of Charles F. Kettering, the inventor, Randolph’s campaign plans seemed about to topple.

Halle, The Grand Original, 1

They compromised by Randolph joining her for the dinner with Kettering, then her joining him in the country. Once there, Randolph

...decided against ‘hunting those poor defenseless beasts.’ So—–waving off the crestfallen hunters—–he stood in front of the fireplace and began rehearsing what he would say the next day to an audience of the English-Speaking Union.

Halle, The Grand Original, 2

He talked to Kay about his father, Winston Churchill, his childhood, and his dreams of a career in Parliament. Kay wrote

With this frank self-analysis Randolph took the coach out from under any amateur psychoanalysis.

Halle, The Grand Original, 4

Randolph extended his tour, and returned regularly to Cleveland, trying to convince Kay to marry him.

Randolph had travelled to America with his father in 1929. Now his mother, Clementine Churchill, travelled alone to visit him. She sailed on a luxury ocean liner, ordering manicures, massages, and dinner in bed. According to the biography Clementine: The Life of Mrs. Winston Churchill, Randolph had been an indolent child, and his mother his sole disciplinarian. He recalled his mother visiting him while he was a nine-year-old at boarding school:

My mother came down on a Saturday to take me out and slapped my face in front of the other boys. That was the moment I knew she hated me.

Sonia Purnell, Clementine: The Life of Mrs. Winston Churchill (New York: Viking, 2015), 182.

When Clementine arrived in New York, in February 1931, she was surprised when Randolph greeted her warmly. She wrote to her husband,

[Randolph is a darling. He has quite captivated me . . . & he seems to enjoy my company . . . It is quite like a honeymoon.

Purnell, 198.

She wrote to Winston that Randolph hoped to marry Kay Halle in October of 1931.

He intends to marry her if he can persuade her to do so. He has already asked her several times and been put off…”

Thomas Maier, When Lions Roar: The Churchills and the Kennedys (Crown, 2014), 43

Clementine did not credit Kay’s influence as improving the relationship between mother and son, and her biographer credited it to being away from Winston, whom she said spoiled their son. Clementine did feel that she should interfere with his relationship with Kay. She told Sam and Blanche Halle that Randolph should finish school before thinking of marriage; they readily agreed.

It seems that the Halles did not explain that while Clementine’s son was just 19, and had had no steady means of support, there daughter was a 27-year-old woman who knew her own mind. She could make her own decisions. Evidence suggests that, while she enjoyed Randolph’s company, she was not at all eager to marry him. She thought him too temperamental and restless to marry. (His later marriages would prove her correct.)

Kay recalled that when she was with Randolph at the family cabin, he shared a letter from his father stating,

The best thing you tell me about Miss Halle is that she has a draught of Jewish blood—–God knows we need it in our family.

James M. Wood, Halle’s: Memoirs of a Family Department Store (Cleveland: Geranium Press, 1987), 139.

Left photo is a snapshot from Kay’s papers. Top center photo is from October 1963, when Randolph and Kay visited their mutual friend John F. Kennedy in the White House.

The romance had cooled by the spring of 1932, when Kay was living in London for the year, writing a weekly newspaper column. Her dispatches from London would appear in Cleveland newspapers. Kay and Randolph had developed a deep friendship, so Kay was comfortable visiting the Churchill family at Chartwell as a friend, not an intended wife. There she began a long friendship with Winston. She would maintain these friendships, with both Winston and Randolph, throughout their lives. She would publish two books about Winston Churchill, and another about Randolph.

Kay returned to the U.S. to work on Franklin Roosevelt’s presidential campaign. She was a close friend to FDR’s daughter-in-law Betsy Cushing Roosevelt. During the campaign, Kay met Joseph Kennedy. In October of 1933, Kay travelled to England with James and Betsy Roosevelt, and Joseph and Rose Kennedy. She and the young Roosevelts had a memorable visit to Chartwell, when Winston discussed his vision of a combined U.S./Great Britain currency, sending a sketch with James back to FDR. Joe Kennedy met Churchill during this visit, as he was working to secure liquor distribution rights for the end of prohibition.

Between Kay’s first two visits to Chartwell, Winston Churchill would visit the U.S. on his own speaking tour, visiting the Halles on Harcourt Drive in 1932.

During the Great Depression in England, the Churchills’ expenses far exceeded their income. Being a statesman brought little financial reward on its own; Winston Churchill made money from his words as a gifted speaker and writer. As he would remark, “I live from mouth to hand!”

During the Great Depression in Cleveland, the Halles remained comfortable, but many unemployed men would knock on the kitchen door, asking for food in exchange for yard work. The cook, Kitty Muessel, was known for her pastries and her big heart. She was happy to feed anyone in need. As an Irish woman, she at first refused to cook for Winston Churchill, based on his stand on Ireland.

The meal was negotiated and served. Kitty, like the rest of the family, was won over, and approved of the close relationships that developed between the entire Halle family and the Churchills, for years to come.

After dinner was another hurdle to overcome. Kay had earlier alerted her mother that Mr. Churchill always had a nightcap (or two) of whiskey before bed. It was Prohibition in America, and Sam didn’t drink. Blanche called Al Muller, a buyer at the store, and explained her dilemma. He said not to worry. A bottle of good Scotch, smuggled in from Canada, arrived the next day.

When Winston said goodnight after the elegant meal, Blanche offered him the bottle and asked if he would like to take it upstairs.

“My dear Mrs. Halle, what makes you think I would want to take a bottle of Scotch to bed?” he asked.

“Mr. Churchill,” Blanche responded, not missing a beat, “we offer this to all our house guests.”

“In that case, I’ll take it,” he said, and headed upstairs to the guest bedroom over the kitchen, which is now called the “Churchill bedroom.” (Halle’s, 138)

Decades later, Kay would be instrumental in Churchill being named the first honorary citizen of the United States.

Other Famous Guests

The three Churchills were not the only famous houseguests.

Winsor French recalled meeting Russian-born composer Nicolas Nabokov when he was a houseguest of the Halles in 1936. One of the composer’s pieces was receiving a world premiere with the Cleveland Orchestra. French called Nabokov, a cousin to author Vladimir Nabokov, ” ‘a floorshow all in himself,’ entertaining guests with his ‘biting and acid’ impersonations of celebrities.” (James M. Wood, Out and About with Winsor French, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2011, 111.)

Arthur Rubinstein stayed with the Halles when he was a soloist with Cleveland Orchestra at Severance Hall. George Gershwin and Oscar Levant visited. Both Sam and Kay played the piano, and the Halle’s were long-time orchestra supporters. A 1943 Movie-Radio Guide article gave full credit to Kay Halle for getting the Cleveland Orchestra. She became the intermission commenter on CBS radio, and traveled with the orchestra. As the article said of Kay, “She knows practically everyone in music, and outside of it.” (Robert Bagar, “Classical Music,” Movie-Radio Guide, May 1943, 11.)

Vita Sackville-West and Sir Harold Nicholson, Louis Bromfield, and Admiral Richard Byrd were also said to have visited the house.

When Case Western Reserve University bought Harcourt House in 1987, a mention in the newspaper included these sentences,

The stately brick residence is filled with history. Cole Porter composed the song “Night and Day,” there and Winston Churchill and novelist Sinclair Lewis were among the many notables who slept there.

William F. Miller, “Decent Digs,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 14, 1987

As described above, Winston Churchill most certainly spent the night at Harcourt House, and since he was supplied with his regular nightcap, we can assume he slept well.

Sinclair Lewis visited Halle Bros. store in what was one of the store many innovations: having authors come to the store to sign books. He likely visited the Harcourt home after a store visit. Lewis included the store in his 1945 novel Cass Timberlane. Describing the town center of Grand Republic, an imaginary small city in Central Minnesota, he wrote of the Blue Ox National Bank, a bookstore, and “the Bozard Beaux Arts Women’s Specialty Shops, which everyone said was just as smart as New York or Halle Brothers of Cleveland.”

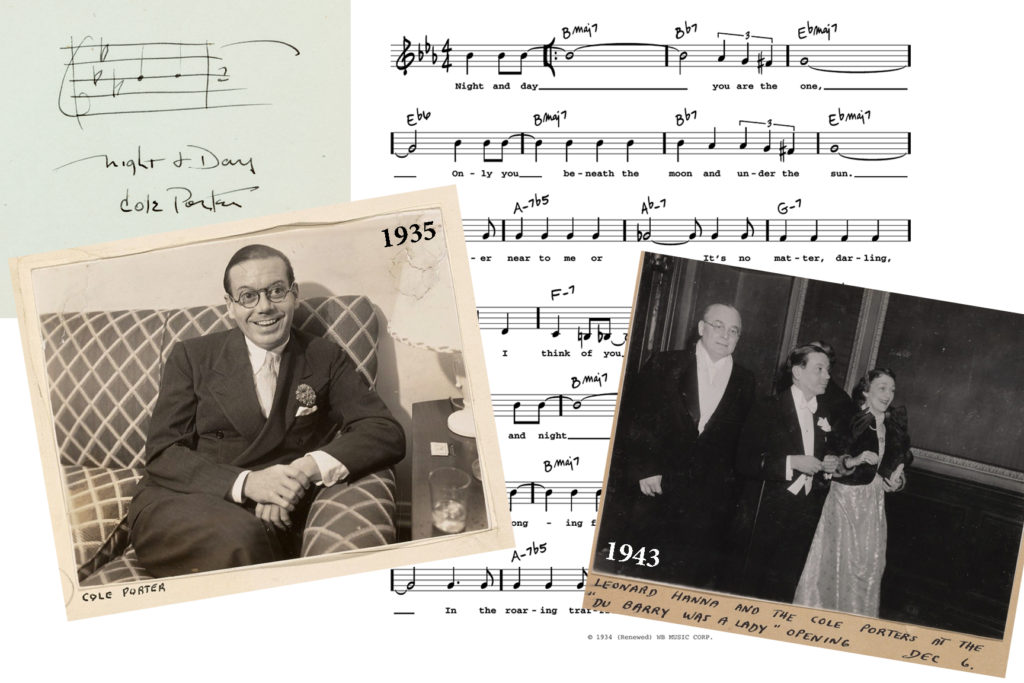

Cole Porter — Night and Day

By all accounts, members of the Halle family knew many illustrious individuals, and welcomed many people into their home. Sam Halle liked to play Chopin on the Steinway piano in Harcourt, he and daughter Kay were both quite competent as pianists. But did Cole Porter really visit the Halle’s living room long enough to write his most famous song?

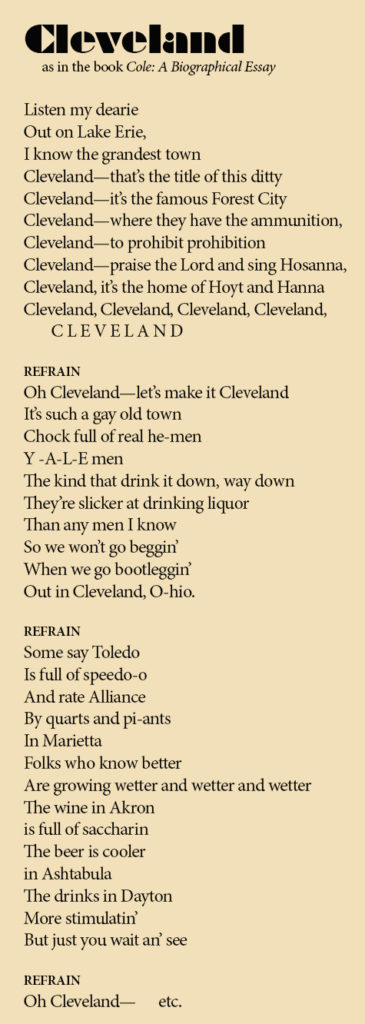

It seems Cole Porter wrote the first of several songs in greater Cleveland in 1924. He had performed with a group of Yale students in Cincinnati in 1914. As Johnfritz Achelis recalled,

Apparently we were a success because a few years later the reunion was in Cleveland, and we were asked again to assemble the show. Len Hanna was the manager. We arrived in Mentor at 6 AM in cold, cold weather. Len was there and lead us to the waiting room where we were liberally served hot rums. Some of us were put up in the Tavern Club and the rest at the other end of “Liquid” (Euclid) Avenue at Len’s house. For this occasion Cole wrote Cleveland. He wired the words to us in New York and we learned them on the train.”

Cole: A Biographical Essay by Brendan Gill (Holt, Pinehart & Winston, 1971), 26–27

Leonard Hanna Jr.’s home (designed by Abram Garfield) on East Boulevard is now part of the Western Reserve Historical Society’s Cleveland History Center in University Circle. Yale alum Warren Corning Wick recalled,

Leonard said Cole must close himself in his library, where he had a small upright piano moved. The butler was there with drinks and, closing the door, they told Cole he couldn’t come out until he’d written the song. 20 or 30 minutes later, Cole sheepishly asked, “Can I come out now? I have a song.” The song being, ‘Let’s Make It Cleveland.’ Not untimely, it was about prohibition, 1924 being the heart of it. Cole sang it himself at the University Club, that night in Cleveland, and received a standing ovation.

My Recollections of Old Cleveland by Warren Corning Wick, MSL Academic Endeavors, Cleveland, Ohio, 2019, 293–296)

So Cole Porter was in Cleveland, and wrote a song at someone else’s piano in a half hour. (The song Cleveland is charming, but certainly no Night and Day.)

Porter would visit Hanna and Cleveland into the 1930s and 40s, often staying at Hanna’s Hilo estate in Kirtland. He composed songs there, including for a show titled Star Dust, that was never produced, but he reused I Get a Kick Out of You.

Through Hanna, Cole Porter became friends with Winsor French (1904–1973), who was also a close Halle family friend and neighbor. The book Halle’s states that French “first asked Kay Halle, and then her sister Margaret, to marry him, but, though twice-refused, remained a good friend of the family.” He recalled spending many hours in the Halle home on Harcourt, and visited Kay so regularly in Washington, DC, that he called her home “Hotel Halle.”

In 1933, Winsor married Margaret Hall Frueauff, daughter of Antionette Perry, namesake of the Toni Awards. She was an accomplished actress using the name Margaret Perry. Their marriage was short-lived, but they remained friends. French wrote an About Town column for many years. Although a newspaperman, he owned a silver Rolls Royce due to a wad of IBM stock casually given to him by Hanna. (He showed an egalitarian side by riding up front next to his driver, rather than in the back.)

In March and April of 1936, French lived in Cole and Linda Porter’s guesthouse in Hollywood. He delighted in a dinner party thrown by Marlene Dietrich (she cooked) when Cole sat at the piano to play his latest compositions.

As described below, Kay Halle was friends with George Gershwin as early as 1929, and they would often visit each other’s New York apartments; Cole Porter may have been in their group of friends. Jerome Zerbe photographed both Kay Halle and Cole Porter at El Morocco in the 1930s. There were many connections between Cole Porter and Cleveland, and several between Porter and the Halles, but it seems unlikely he wrote his most famous song on Harcourt Drive.

The true story was conveyed by a Halle daughter for the 1970s publication In Our Day, Cleveland Heights: Its People, Its Places, Its Past. Then the story was exaggerated.

The truth about Night and Day: A friend of the Halle family (whether Hanna, French, Zerbe, or another, was not stated) brought his good friend Cole Porter to the Halle’s home. Cole Porter “sat down at the piano and played for the first time a song he had been working on: Night and Day.”

Summertime

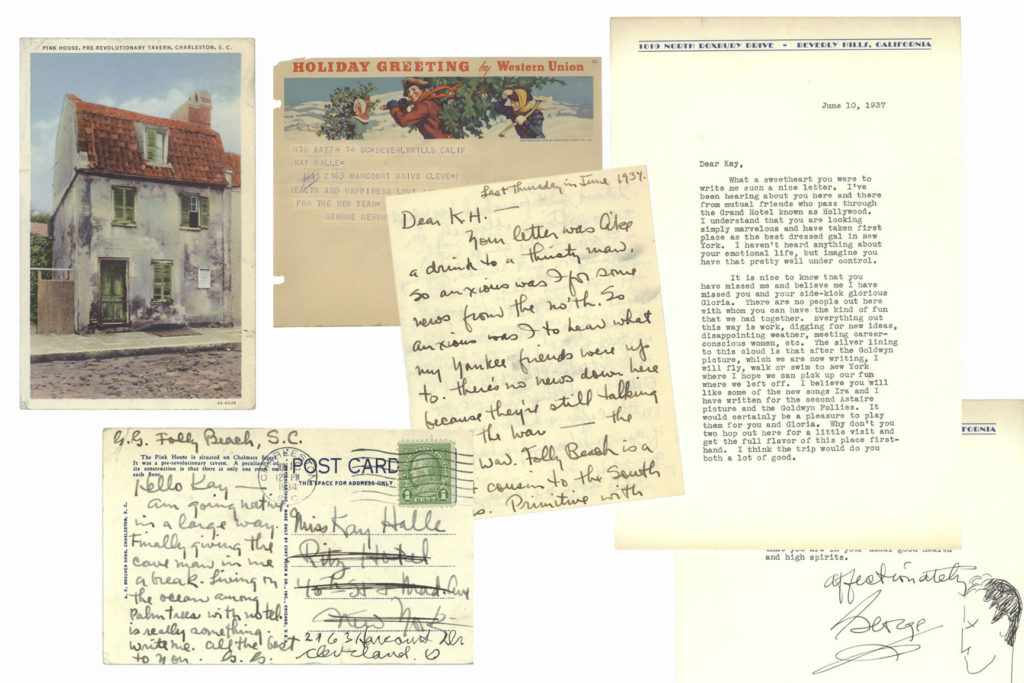

George Gershwin (1898–1937) visited the Halles, and was known as an intimate friend of eldest daughter Kay. Kay wrote about him in 1978, four decades after his death.

I first met George Gershwin after he performed the piano solo of his “Rhapsody in Blue” [written in 1924] in Cleveland's Public Music Hall. That encounter deepened into a friendship that lasted until George died tragically of a brain tumor at 38. . . . In 1934, while George was composing his ‘Porgy and Bess,’ based on DuBose Heyward's novel, ‘Porgy,’ I would receive ecstatic letters from Folly Beach in South Carolina. . . . But back in New York there was the painful period when he was giving birth to “Porgy and Bess”—–especially the lullaby. . . . Restlessness would often lead him to my Steinway baby grand piano, selected by Artur Rubinstein, which George particularly fancied. The desk clerk at the Elysee knew that if I was out he was to give George the key to my room so that he might ‘draw inspiration’ from my piano. George could not retreat to the country to compose as he ‘became too aware of the rhythm of the insects and the other sounds of nature.’ One night, on returning from the theater, I heard music drifting from my room. As I entered, George bade me ‘Sit down, I think I've got the lullaby!’ And in his high, Wailing-Wall voice, he sang ‘Summertime.’ Overcome with its loveliness, I agreed: he had, indeed, ‘gotten it.’

Kay Halle, “The Time of His Life,” The Washington Post, February 5, 1978

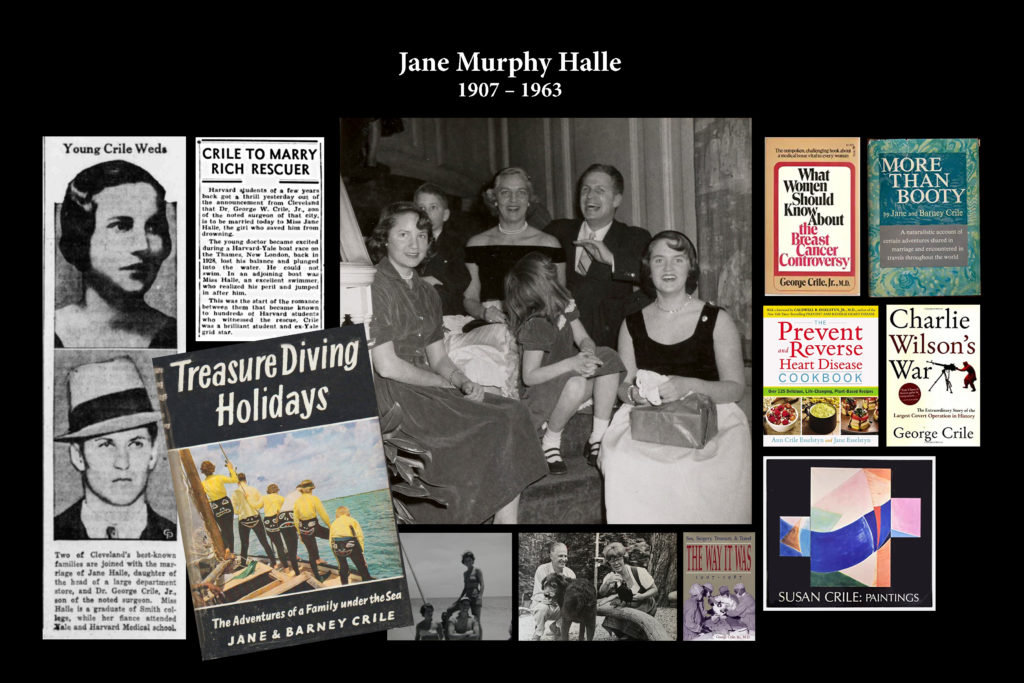

Kay wrote that George invited her, and her sister Jane Crile, to lunch. Then they joined him as he auditioned Todd Duncan for Porgy in the musical. The on

…opening night of ‘Porgy and Bess,’ in Boston on Sept. 25, 1935, was ecstasy for those who had lived through its birth pangs with George, for we knew we were witnessing musical history.

Kay Halle, “The Time of His Life”

George joined Kay at a New Year’s party at the White House on December 29, 1934, where President Roosevelt asked him to sing. Gershwin was deeply moved.

Isamu Noguchi and George Gershwin

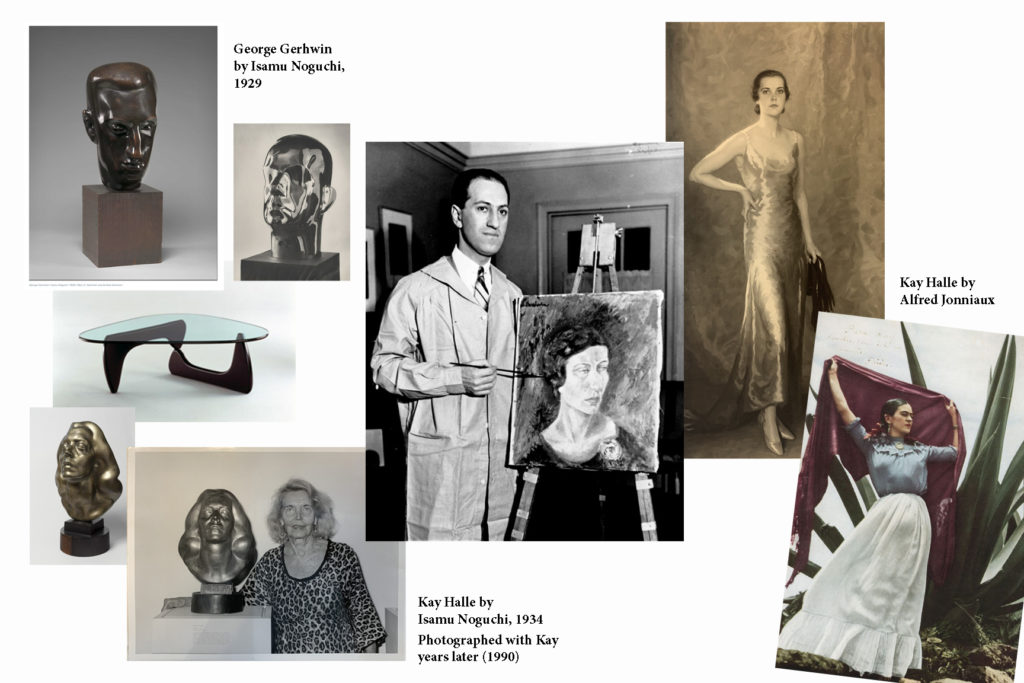

Kay introduced George Gershwin to artist and designer Isamu Noguchi in 1929, and encouraged George to buy some of the then-struggling artist’s sculptures. According to the National Portrait Gallery website,

Early in 1929, George and Ira moved into adjoining penthouses on Riverside Drive and George began to paint and collect art. . . . He met Noguchi through Kay Halle, a glamorous, wealthy and talented woman whose apartment was a gathering place for those prominent in the arts and politics. Halle sold Gershwin a sculpture by Noguchi, and soon he sat for his portrait. . . . Noguchi traveled to Cambridge and to Chicago with his good friend, Buckminster Fuller. . . . Noguchi remained a friend to Gershwin, as well, attending dinner parties at his home with Halle and Fuller. Their last meeting seems to have been at a party given in Gershwin’s honor in Mexico City in 1936.

National Portrait Gallery blog at https://npg.si.edu/blog/george-gershwin-and-isamu-noguchi-1929

Buckminster Fuller was also known to be an intimate friend to Kay Halle. George Gershwin drew a portrait of Kay that is in the National Portrait Gallery.

In November 1935, Kay was with Gershwin and Noguchi in Mexico when they “hung out” with Diego Rivera and Freda Kahlo.

George was regularly writing to Kay from Hollywood, including a letter a few weeks before his 1937 death from a brain tumor.

The next generation

By 1940, the four younger children were married. Blanche and Samuel had a dozen grandchildren, who all joined them for a photo in the Harcourt library in 1945.

The 1950s

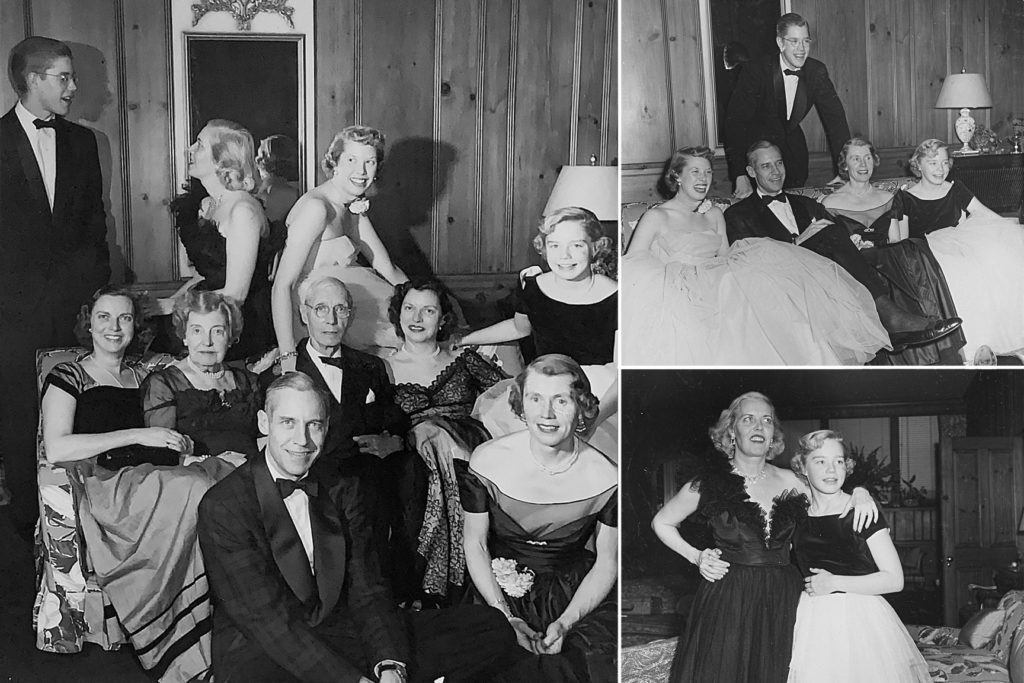

There were several milestones in the Halle family in 1951. Eldest grandchild, Walter’s daughter Helen, married at Trinity Church on February 2, 1951, her parents’ twentieth wedding anniversary. One of the celebratory parties was at the Harcourt home. Jerome Zerbe took photos at the party and the wedding.

Blanche and Sam celebrated their fifth wedding anniversary in July 1951, with a family party on Harcourt Drive that had been the setting of many events in their lives over the previous thirty-five years. They moved in with four young children, now those children were accomplished adults, and they had 12 grandchildren, all there for the party, along with their white poodle, Winston, named, of course, for Sir Churchill.

Blanche would die that October, at age 77.

Samuel remained in the house, but he was not alone. He had family nearby, he had a second family at the store, and, although Kitty Muessel, who served as cook for the family for 38 years, had died a few years earlier, he still had two women helping care for the house. The large house, previously filled with the happy sounds of a wife and five children, must have been mournfully quiet after Blanche’s death.

“Mister Halle,” Anne Sinnin, from Halle’s public relations department, asked, “Why do you insist on living in that big, rambling home when a smaller one would do just as well?” His response exemplified his feeling of responsibility toward others, and to the women working in his home. “I can’t leave that place, Anne. I’ve got to make a home for those two women.” (Source: Letter signed L.A.T. in Kaye Halle’s papers.)

Sam continued to go in to work daily, although he took the day off every year on his birthday, July 8, to avoid well-wishers interrupting work. In 1954, that day off merited a newspaper article announcing he had turned 86.

On August 11, 1954, Samuel Halle had a normal workday, touring the store, observing operations, and greeting friends and employees. He died that night in his sleep, in his bed in the house on Harcourt Drive. Daughter Kay discovered him in the morning.

A memorial service was held in the store, with 2,000 guests expected.

Kay had written to a sister Jane of their father’s “incandescent personality,” his “warmth of character simple honesty and integrity,” and his “goodness and purity.” She wrote, “I think it can be said of Halle Brothers as I believe Emerson once said—that ‘an institution is the lengthening shadow of one man.’. . . “Father has that magical quality known as presence.”

After Samuel’s passing, his children remained close. Walter ran Halle Brothers, the family business, and his four sisters were never shy about giving him advice. In 1966, when Walter became ill and needed heart surgery, he accepted the role of board chairman and his Chisholm, just 33, became president.

After the stores closed in 1982, employees saved papers and memorabilia and gave cartons of material to Ann and Maggie, who organized the material and had the history published as Halle’s, Memoirs of a Family Department Store. The book describes the four sisters:

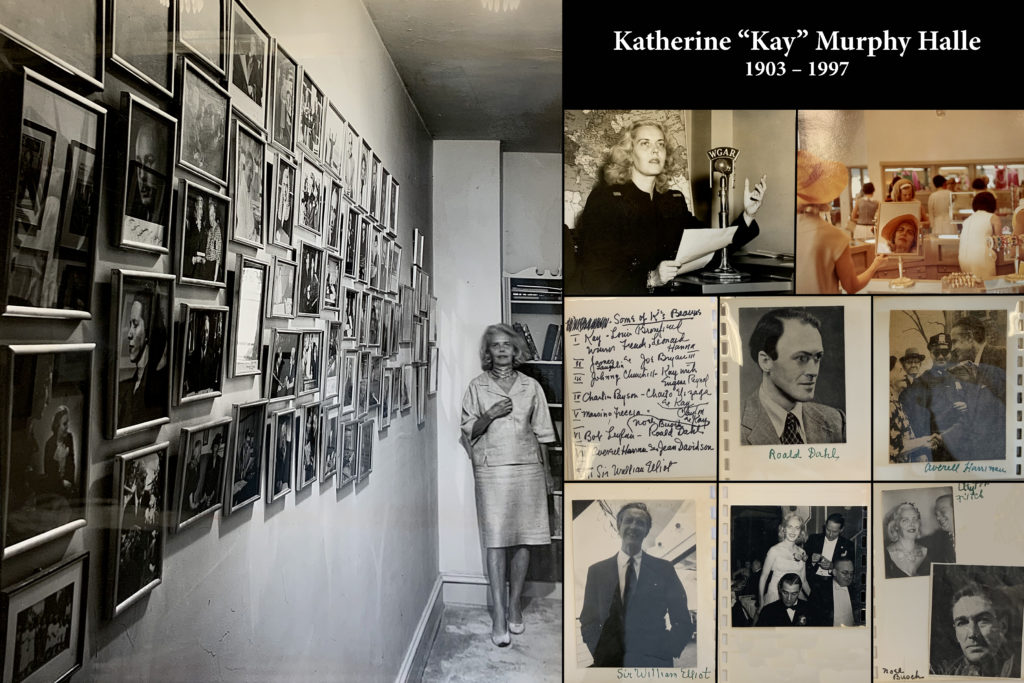

Sam and Blanche had raised free spirits. Margaret had eloped with Francis Sherwin, son of Sam’s banker, John Sherwin. Jane had married George Crile, Jr., nicknamed Barney, son of Cleveland Clinic’s founder George Crile. Both men were renowned pioneering surgeons. Ann had married Robert Little, the son of Clarence C. Little, a famous geneticist who founded the Jackson Laboratory of Cancer Research in Bar Harbor, Maine. His family could trace its roots to Paul Revere. Kay never married, but her escorts were legendary, from Randolph Churchill to George Gershwin to sculptor Isamu Noguchi. Kay, a former employee of the Office of Strategic Services, America’s World War II intelligence office, had moved to Washington, D.C., by the Fifties, where her Georgetown home became a glittering salon.

Wood, Halle’s, 181

Above left: Kay Halle with her “famous people wall” from the second floor of her Washington DC home.

Above right row 1: Kay on the radio, Kay in Halle’s

Above right rows 2 and 3: A few of the snapshots in an album with a page “some of K’s beaus”

Kay Halle was a fascinating woman, and there is much that could be written about her. She would live in the Harcourt home for the longest of the children, albeit occasionally, appearing at that address in the census in 1930 and 1940, even as she lived on her own in New York City and Washington DC. She visited so regularly that she maintained her voter registration in Cleveland. (The Plain Dealer mentioned that she travelled from Washington to vote in 1954.) Her personal papers—about 50,850 items total, boxed and stored in over 105 linear feet—are in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston.

As a short summary, following are excerpts from her obituary in the New York Times:

Kay Halle, a glamorous Cleveland department store heiress who cut a heady swath through the 20th century firmament, befriending and bewitching luminaries on both sides of the Atlantic. . . .

During a remarkable life in which she formed enduring intimate relationships with George Gershwin, Randolph Churchill, W. Averell Harriman, Joseph P. Kennedy, Walter Lippmann, Buckminster Fuller and scores of other diverse figures. . .

She had a creditable enough career in journalism and with American intelligence in World War II. But Miss Halle, who wrote for The Cleveland Plain Dealer and other publications, conducted radio interviews with public figures and provided intermission commentary for Cleveland Orchestra broadcasts, was at her best in private settings.

A tall, slender, blonde beauty. . . [she] once showed a friend a list of 64 men who had proposed to her, among them a youthful Randolph Churchill and an aging Averell Harriman. . . .

Given the range and ardor of her admirers, one of Miss Halle's more notable achievements may have been avoiding marriage and thriving in an era when even independently wealthy spinsters were viewed with suspicion. . . .

Even more notable was the fact that she remained on such good terms with her spurned suitors. . . .

Even intimates who are certain, for example, that she had been Joseph Kennedy's favorite mistress cannot say for sure whether her friendship with Gershwin, who wrote her gushing letters, had been a full-fledged romance.

A product of a fairy-tale union between a wealthy German-Jewish merchant and an Irish-Catholic working girl, Miss Halle, whose father was a founder of the old Halle Brothers department store in Cleveland, grew up in an ecumenical, intellectually charged atmosphere that left her without prejudice or pretension and with an eclectic range of interests, especially in people.

Making the most of her family connections and even more of those she formed on her own, Miss Halle got her start in political society early. During a family visit to Washington when she was 13, President Woodrow Wilson's Secretary of War, Newton D. Baker, a former Cleveland mayor, had a young assistant, Walter Lippmann, show her around. He got her admitted to a special session of Congress, making her perhaps the last person alive to have witnessed Wilson's request for a declaration of war in April 1917.

Later, after one boring year at Smith College, Miss Halle took New York by storm, captivating Gershwin and making her apartment a headquarters of the roaring 20's. . . . she became a frequent visitor to Chartwell, the Churchill country home in England, and a favorite of his father, Sir Winston Churchill.

As a result, Miss Halle, who was an old friend of Franklin D. Roosevelt and campaigned for him in 1932, became one of the few people to be on intimate family terms with the two wartime leaders.

Miss Halle, who made Washington her base after World War II, became such a Churchill enthusiast that she published two volumes of his collected sayings and was credited with using her considerable drawing room influence to persuade Congress to confer the honorary American citizenship that he considered his most prized public tribute.

Source: Robert Mcg. Thomas Jr., “Kay Halle, 93, an Intimate of Century’s Giants,” New York Times, August 24, 1997, Section 1, p.33

Walter married Helen Chisholm (1908–1992) in 1929. Helen Chisholm was the great granddaughter of Scottish immigrant Henry Chisholm (1822–1881), who was the owner of the Cleveland Rolling Mill, and became known as father of the Cleveland steel trade. (It is a coincidence that a portrait of Helen’s first cousin one removed, Josephine Chisholm Brainerd, has recently been hung in the family home of her husband on Harcourt Drive.) Jackie Kennedy, who was a friend to Kay Halle, asked Helen to help with redecorating the White House.

Walter and Helen’s three children were Helen Chisholm Halle Foster Neubauer (1929–1978), Chisholm Halle (1933–1982), and Kate Halle Briggs (b.1939).

Walter’s obituary in the New York Times:

Walter Murphy Halle, retired board chairman and chief executive officer of the Halle Bros. Co. department store chain, died today at his home in Waite Hill. He was 67 years old. Mr. Halle retired on May 1, 1971, after 43 years with the chain. His father, Samuel Halle, was a co‐founder of Halle's, which became a subsidiary of Marshall Field & Co., in 1970. Mr. Halle was a graduate of Princeton University. He joined the family operated department store in 1927, and became general merchandise manager 12 years later. He succeeded his father as store president in 1946 and held that post until 1966, when his son, Chisholm, succeeded him. During World War II, Mr. Halle served in the Air Force, and was discharged in 1945 with the rank of lieutenant colonel. Mr. Halle had been a trustee of the Ohio Retail Merchants Association, Oberlin College, Cleveland Trust Bank, Cleveland Clinic and the Musical Arts Association, which operates the Cleveland Orchestra. In addition to his son, Mr. Halle leaves his wife, Helen; two daughters, Mrs. Fritz Neubauer and Mrs. John H. Briggs Jr.; three sisters, Mrs. Francis Sherwin, Mrs. Robert Little and Miss Kay Halle, and 13 grandchildren.

Source: “Walter M. Halle, 67; Headed Store Chain,” New York Times, January 11, 1972, p.40

1910: Margaret, second from left, as a playful child, with her first three siblings; 1945: Maggie’s father and three sons; 1955: Maggie and Kay in Italy; Right photos: Sherwin Preserve of the Waite Hill Land Conservancy

Time magazine included this notice under “Milestones” on February 9, 1931:

Eloped. Margaret, socialite daughter of President Samuel H. Halle of Halle Bros., Cleveland department store; and Francis M. Sherwin, young Yale graduate, son of Banker John Sherwin of Cleveland. Without telling their parents, they went to Grace Church, Cleveland, were married.

As a brief description of the family of Francis McIntosh Sherwin (1906–1969): When Francis’s father died in 1934, at age 65, an article in the New York Times included these headlines: