Historians estimate ten to fifteen percent of soldiers in the Revolution were Black, according to U.S. Army historian Maj. Glenn Williams.[1]

The Daughters of the American Revolution organization states that “More than 5,000 African American or mixed descent patriots served in the American Revolution. Military service is credited to those who served in campaigns against the British between 19 April 1775 and 26 November 1783.”[2]

The first American casualty of the Revolution

Crispus Attucks, of African and Native American descent, was the first person killed in the Boston Massacre, and therefore the first American killed in the Revolution. Black soldiers fought at Lexington and Concord, including Prince Easterbrooks, who was wounded.

The first major battle of the American Revolution

After the first major battle of the American Revolution, the Battle of Bunker Hill, fourteen officers sent a petition asking for one-of-a-kind recognition for a soldier:

“To the Honorable General Court of the Massachusetts Bay: The subscribers beg leave to report to your Honorable House (which we do in justice to the character of so brave a man), that, under our own observation, we declare that a … man, called Salem Poor, of Col. Frye’s regiment, Capt. Ames’ company, in the late battle at Charlestown, behaved like an experienced officer, as well as an excellent soldier. To set forth particulars of his conduct would be tedious. We would beg leave to say, in the person of this said …, centers a brave and gallant soldier. The reward due to so great and distinguished a character, we submit to the Congress.”[3]

No one suggested that the excellent soldier who behaved like an experienced officer should actually be promoted to an officer position. The word twice replaced by ellipses in the above quote was “negro.”

Salem Poor was born into slavery in Massachusetts in 1747, purchased his freedom in 1769, and enlisted in the militia in 1775. At the Battle of Bunker Hill, of the eight-hundred-fifty soldier fighting for the Patriots, more than a hundred were African American and Native American. Later in the war, Salem Poor fought at the Battle of White Plains, the Battles of Saratoga, spent the winter with the troops at Valley Forge, and fought at the Battle of Monmouth.[4]

Washington didn’t cross the Delaware alone

The famous painting Washington Crossing the Delaware (by Emanuel Leutze, 1851) shows three men in front of Washington in the bow of the boat: a frontier man in a coonskin cap, a Scotsman in a tam o’shanter hat,[5] and a Black man. The diverse portraits could be merely representational of many who served, but the Black man may well be William Lee.[6]

William Lee was born into slavery. When he was sixteen years of age he was sold to George Washington. He accompanied Washington on surveying missions in 1770, to the First Continental Congress in 1774, and through all eight years of the American Revolution.

General George Washington, like other slave owners, opposed arming enslaved soldiers. While Black soldiers served with him in the French and Indian War, including William Lee and Barzillai Lew, they had support roles such as manual laborers or drummers, and were not armed. Training and arming slaves seemed to be inviting rebellion.

When Washington was made commander in chief, he forbade recruiting Black soldiers.

Thousands of Blacks fought for freedom with the British

On November 7, 1775, in a shrewd effort to divide the colonies, the deposed royal governor of Virginia, John Murray, a.k.a. Lord Dunmore, issued a proclamation establishing marshal law and offering freedom to the enslaved, stating

“I do hereby farther declare all indented servants, Negroes, or others (appertaining to rebels) free that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining his Majesty’s Troops, as soon as may be, for the more speedily reducing this colony to a proper sense of their duty, to his Majesty’s crown and dignity.”

Many took Dunmore up on the offer, and formed a group known as the “Ethiopian Regiment.”[7]

Note that only those enslaved by the rebels were freed. Hopeful soldiers who were enslaved by Loyalists were sent back to their enslavers.

Some British officers refused to take Black soldiers. Then in 1778, British Sir Henry Clinton promised in the Philippsburg Declaration, “every Negro who shall desert the Rebel Standard, [is granted] full security to follow within these Lines, any Occupation which he shall think proper.”

Thousands of enslaved men joined the British.

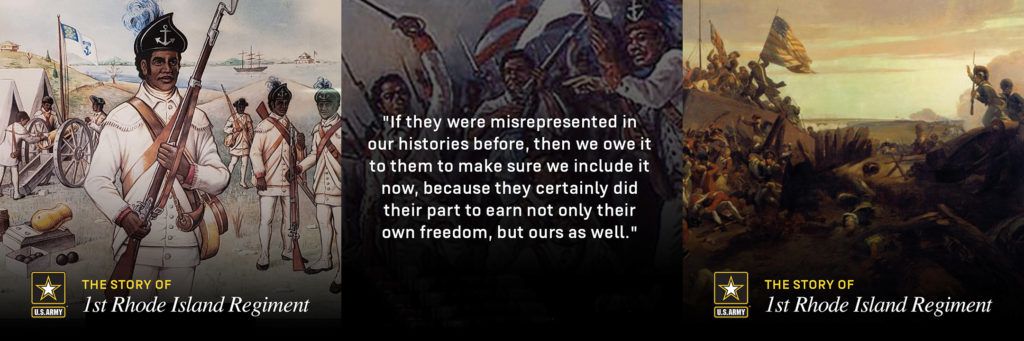

The 1781 painting shows a Black soldier of the First Rhode Island Regiment, a New England militiaman, a frontier rifleman, and a French officer.

The diary is part of the collection of the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection at Brown University.

Free Blacks became Patriots

The Continental Army, with the impetus of the British competition, began recruiting Black soldiers. Washington was a pragmatist. Virginia instituted a draft, but only allowed free Black men, and they served “without arms,” as wagoners, cooks, waiters or artisans. Many runaways claimed to be free and signed up.

Each colony/state was both independent in its efforts to recruit state militia, and was responsible for supporting the needs established by the Continental Congress. The states could decide how to do this for themselves. New Jersey permitted slaves as substitutes. Some New Jersey slave owners who were conscripted sent enslaved men in their places, with the owner also taking the enslaved man’s pay. New Hampshire and Connecticut also recruited enslaved men.

One New Hampshire man, Jude Hall, who had born into slavery in Exeter, served the entire war. He was in the battles of Bunker Hill, Ticonderoga, Trenton, Hubbarton, Saratoga, and Monmouth, and served at Valley Forge. After the war, three of Hall’s adult sons were kidnapped in New Hampshire and sold into slavery.

The Rhode Island Regiment

Rhode Island had a complicated history with slavery. In 1652 Rhode Island had passed a law that limited indentured servitude to ten years, including for those of African descent. The law was ignored.[8]

Rhode Island merchants became the leaders in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, sending 514 slave ships to West Africa during the colonial period. (The rest of the colonies combined sent 189 ships.) In 1713, the slave traders began a triangular route, trading Rhode Island rum (there were thirty distilleries in the colony) for African captives, who were transported (in horrific conditions across the Atlantic) to the Caribbean, where they were traded for sugar and molasses to go to Rhode Island to make more rum. Enough of the kidnapped Africans were brought to Rhode Island that the colony had the highest percentage of enslaved people in New England.[9]

When Rhode Island struggled to recruit their quota of soldiers, General James Varnum of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment suggested recruiting slaves. The Rhode Island Assembly offered freedom to every able-bodied male slave, regardless of race, who enlisted, and paid their slave masters market value for their emancipation. More than 140 immediately signed up and throughout the war 250 former slaves and freemen served. The unit fought in the decisive battle at Yorktown.

The 1st Rhode Island Regiment was a segregated unit, with white officers and separate companies for White and Black soldiers. It is said to have been the only segregated unit, but there were also all-Black units in Connecticut and Massachusetts.

Don Troiani’s painting, “Brave Men as Ever Fought” was commissioned by the Museum of the American Revolution, with funding from the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail of the National Park Service. Read about the painting at Museum of the American Revolution website.

The most integrated Army

In the rest of the Continental Army, Black and White soldiers served together. In fact, Army historian Glenn Williams stated,

I’ve heard one analysis say that the Army during the Revolutionary War was the most integrated that the Army would be until the Korean War. World War I and World War II both, and of course in the Civil War, there were lots of blacks in uniform, but the men were segregated into separate units. Even the Rhode Island regiment was half black, half white, and the men were segregated into their own companies, but in the rest of the Army, they were integrated throughout the regiments.

After the American Revolution

Black Loyalists, After the War

When the last British was ship left Savannah in 1781, more than 5,000 formerly enslaved Americans were transported to Jamaica or to St. Augustine in Trinidad and Tobago. When the British left Charleston in 1782, another 5,000 were resettled in the West Indies, although more than half were enslaved by Loyalist on plantations there. (While the British had discontinued slavery in England in 1772, they continued the practice in their colonial holdings in the Caribbean.)

Of the enslaved people who made it to New York City when it was occupied by the British, around 200 were taken to London as free people, and 3,000 men, women, and children were resettled in Nova Scotia. When English supporters established Freetown settlement in Sierra Leone, over 1,000 of the Black Loyalists chose to leave Halifax and travel to West Africa.

Black Patriots, After the War

For the “winners,” the rewards were more tenuous. Some soldiers, such as those from Rhode Island, did win their freedom. Others fought for “freedom and independence,” and then returned to enslavement. Some were promised freedom in exchange for service, and then had no recourse if the promise was broken. The Virginia Assembly, reacting to the widespread injustice, passed a bill in 1783 requiring that those who served on the promise of freedom to be freed, but the enslaved people could not initiate proceedings on their own behalf, so only eight people were freed by the decree.

With the critical need for soldiers diminished, states including Connecticut and Massachusetts banned Blacks from service in 1784 and 1785. In 1792, the U.S. Congress voted that only “free able-bodied white male citizens” could serve.

Perhaps inspired by the ideals of the Revolution, Northern states began abolishing slavery and some Southerners began to free slaves. As Abigail Adams had written in 1774, “it always appeared a most iniquitous scheme to me to fight ourselves for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have.”

Many Methodist, Baptist, and Quaker preachers urged manumission (the freeing of enslaved people). The changing economy from labor-intensive tobacco to other crops also decreased the need for slaves.

By 1810, seventy-five percent of the Blacks in the North, and ten percent of Black in the Upper South, were free. Then the widespread use of the cotton gin led to the need for more labor to grow and pick cotton, leading to an increased domestic slave trade.

White Loyalists, After the War

According to historian Maya Jasanoff,

“The fighting actually continued, in the backcountry of the South in particular. And it was in regions like that that loyalists still tried to fight for the empire that they believed in. … It’s a part of the war that we tend to not think too much about or learn about in school. But there was a lot of bloodshed, and particularly in the South. And gangs of revolutionaries, gangs of loyalists, would attack each other, go to each other’s plantations. In fact, some of the big battles in the South happened after the surrender at Yorktown.

“So, what all of this means is that there was a climate of violence and a climate of fear for many loyalists. . . . And so, when the British pulled out in city after city in the United States, up to tens of thousands of loyalists sometimes went with the retreating army to Britain and other parts of the British Empire.

“About half of the loyalists who left the United States ended up going north to Canada, settling in the province of Nova Scotia and also becoming pioneering settlers in the province of New Brunswick.

[In history books, they aren’t often mentioned.] “On the American side, of course, they’re losers. And history is, as we know, written by the winners.”[10]

White Patriots, After the War

The North Carolina Assembly passed an act in 1780 that promised land for service.[11] This land changed the life of many. The text of this act included:

III. And as a farther consideration, be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, that each and every soldier who shall well and truly serve and perform his duty as a soldier. . . and each and every soldier who shall serve out his three years, or to the end of the present war, shall have and receive one prime slave between the age of fifteen and thirty years, or the value thereof in current money, and two hundred acres of land, to be laid off as herein after located and described; and every soldier inlisted [sic] as aforesaid, who may die in the service of his country by the fate of war, sickness, accident, or otherwise, his heirs shall be intitled [sic] to receive his pay, together with the slave and land intended to be given him in virtue of this Act.[12]

“Every soldier . . . shall have and receive one prime slave”?

Stunning.

The Virginia legislature also voted in 1780 to give enslaved persons to recruits. (The “slave bonus” was to be funded by a 5% tax on planters who enslaved people—one human remitted for every 20 owned. The bounty wasn’t given because the slaveholders rebelled against the tax.)

In April 1781 in South Carolina , General Thomas Sumter[13] proposed using enslaved humans as bounties to recruit soldiers (while continuing to reject Black soldiers). Any white man who volunteered for ten months of service would receive one grown, healthy slave. Those who had served and reenlisted could receive up to four enslaved Black people as a recruitment bonus.

When “Sumter’s Law” passed in February, 1782, it was amended to include a bonus to recruiters of one slave for every twenty-five whites enlisted during a two-month period. The bounty was paid with slaves captured or confiscated from Tories, or Loyalist to the British.

Georgia also used slaves confiscated from the plantations of Loyalist for recruitment, as reward, as payment for officials, and in exchange for provisions.[14]

When our remarkable nation—truly the greatest nation ever on earth—was in its idealistic youth, White men who fought for freedom were rewarded with a gift of a man in bondage; Black men who fought for freedom were often returned to bondage. How do we reconcile this with our deep and abiding love and respect for our ancestors and our country?

We can look at our past with open minds and open hearts. As Maya Angelou wrote, “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.”

[1] Elizabeth M. Collins, “Black Soldiers in the Revolutionary War,” Soldiers Live, March 4, 2013. Available at https://www.army.mil/article/97705/black_soldiers_in_the_revolutionary_war

[2] Daughters of the American Revolution, “Researching Your African American Patriot,” DAR.org

[3] https://www.legendsofamerica.com/salem-poor/

[4] In opposition to other expectations and stereotypes of the time, Salem’s first wife, Nancy Parker, was half African American and half Native American. In 1780, he married a second time to Mary Twing, a free African American woman. He married a third time, in 1785, to Sarah Stevens, a white woman.

[5] When reading about Scots-Irish people in Volume Two of this book, you’ll realize that a frontier man in a coonskin cap would likely also be Scottish—a Scots-Irish man—as many served as patriots. (The Highland Scots were more likely to be Loyalists/Tories.)

[6] Others suggest the portrait is Prince Whipple. Whipple was kidnapped into slavery as a child, and was bodyguard to his slave master, New Hampshire Brigadier General William Whipple. Prince was at the Battle of Saratoga. He was one of twenty men who petitioned the New Hampshire legislature for their freedom and the abolishment of slavery in 1779. Prince would be a worthy model for the portrait, but William Lee would have been with Washington as he crossed the Delaware.

[7] Source: Robert A. Selig, “The Revolution’s Black Soldiers,” AmericanRevolution.org/blk.php

[8] Eventually—one hundred thirty-two years after the 1652 law, the state passed the Gradual Emancipation Act of March 1, 1784 declaring children of enslaved people could not be enslaved.

[9] Source: Fred Zilian, Small State Big History: Rhode Island Dominates North American Slave Trade in 18th Century http://smallstatebighistory.com/rhode-island-dominates-north-american-slave-trade-in-18th-century/

[10] Maya Jasanoff, professor of history at Harvard University, National Public Radio interview, July 3, 2015.

[11] One, and only one, Revolutionary War hero who was formerly enslaved was given a land tract in Georgia in appreciation of his military service. Austin Dabney was given freedom for fighting in place of his enslaver. He fought in the Battles of Cowpens and Kettle Creek, and was severely wounded at Kettle Creek.

[12] Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Acts of the North Carolina General Assembly, 1780, Chapter 25. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/

[13] After the War of 1812, the fort in Charleston Harbor was named for General Thomas Sumter. Then this fort named for the man who proposed using humans as currency was the site of the first shots of the American Civil War.

[14] Source: Michael Lee Lanning, African Americans in the Revolutionary War (Citadel Press, 2005)