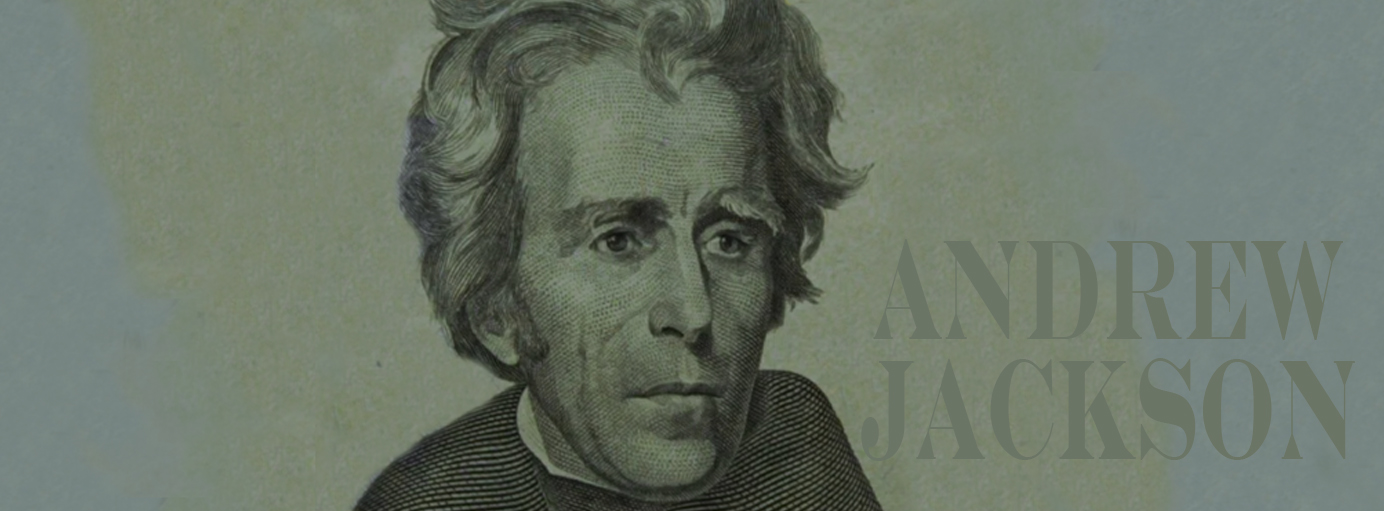

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States, serving from 1829 to 1837. When I was a schoolgirl in Nashville in the 1960s and 1970s, he was held up as a hero. He was an important president and was from my home state of Tennessee, no less. He had a romantic backstory, and we visited the Hermitage, his beautiful home.

Jackson had Scots-Irish roots like many Tennesseans (me included). His nickname was “Old Hickory,” a name used in commemoration throughout Nashville. My parents lived on Old Hickory Boulevard. (This tells you very little about where they lived. The historic road previously looped almost entirely around Nashville. Even after being bisected by the creation of Percy Priest Lake, the road is still nearly seventy miles long.)

Old Hickory, the man, had a big swath of white hair and exuded hyper-masculinity—to the point of toxic masculinity—before it was a named thing. While fighting in a duel, he didn’t flinch after a bullet was lodged in his chest. He wanted to kill his opponent without giving the man the satisfaction of knowing he had been shot.

Despite his war hero status, I never trusted the guy.

Andrew Jackson became famous for fighting Indians, and seemed not only harsh but indiscriminate. He executed British agents in 1818, causing a diplomatic incident. He was quite wealthy and he had, it is true, come from poverty and built his own wealth. That he built that wealth using the labor of enslaved people was overlooked.

He was known as the “people’s president” as voting rights expanded—all the way to permitting free, white men to vote regardless of property ownership. He claimed his first presidential election was stolen from him (with some justification at least, see my election story).

After his inauguration he invited the crowd to the White House, which was promptly trashed. That earned him his second nickname: “King Mob.”

Rights of women, free blacks, and Indians decreased during his presidency. Racism became more pronounced. As a slaveholder with 150 to 300 enslaved workers, he was known for brutality to his enslaved workers, beating a woman publicly for “putting on airs,” and offering an extra $10 to anyone who caught his runaway and gave him 100 lashes. He was not only pro-slavery, he banned the post office from delivering abolitionist literature. He called abolitionists “monsters” who should “atone for this wicked attempt with their lives.”

He was the person most responsible for the “Trail of Tears,” signing seventy acts of Indian removal. Although the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Cherokee, the people were forcibly removed from their homes and thousands—thousands—of people died on the forced march to Oklahoma.

But surely white men—the voters—were doing well, with all the new land available. They would have voted in their own self-interest. Andrew Jackson dismantled the Second Bank of the U.S. (Congress censured him for abuse of power.) His actions helped lead to the Panic of 1837, which started a major depression.

But his Tennessee home, Hermitage, is really beautiful. And Jackson installed indoor plumbing in the White House. And get this: He had a pet African Gray parrot named “Poll.” It is said that he would write to the Hermitage from the White House to inquire about “poor Poll’s health.” You’ve got to love that. Reverend William Menefee Norment was at Jackson’s funeral in 1845 and wrote,

“Before the sermon and while the crowd was gathering, a wicked parrot that was a household pet got excited and commenced swearing so loud and long as to disturb the people and had to be carried from the house.”

The Reverend continued that the excited parrot “let loose perfect gusts of ‘cuss words.’” Mourners were “horrified and awed at the bird’s lack of reverence.” A fitting send off.

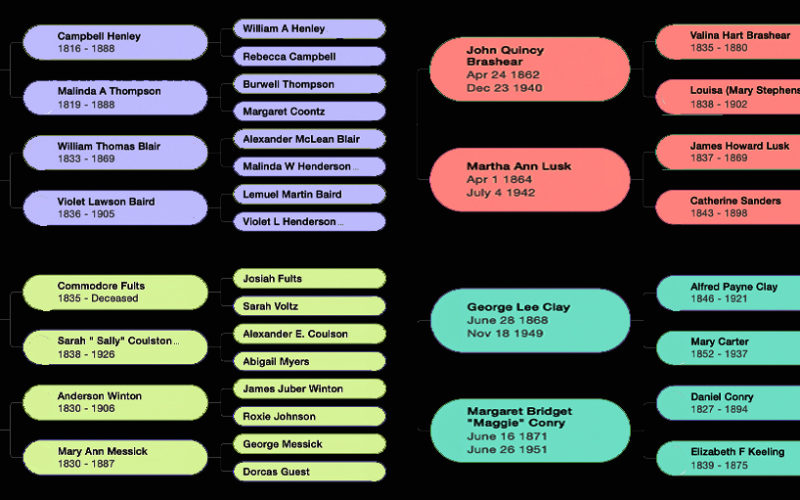

I caution myself not to judge people of the past by today’s standards, so I was heartened to learn that I have two cousins of the Jacksonian Era who not only opposed him, but did so very publicly. Henry Clay, first cousin five times removed of my maternal grandmother Hassie Clay Fults, ran against Jackson for president in 1824 and then helped John Quincy Adams defeat him. Clay ran against Jackson again in 1832. Hugh Lawson White, first cousin four times removed of my paternal grandfather Horace Aubrey Henley, ran against Jackson’s chosen successor for president, Martin Van Buren, in 1836.

Alas, both Henry Clay and Hugh Lawson White lost, but I have the satisfaction of knowing I am following in my ancestors’ footsteps in my dislike of Andrew Jackson.

To read more about presidential pets, see www.PresidentialPetMuseum.com — because it’s a lot of fun. Only one U.S. president had no pets at all.