Looking at America’s British roots and rulers is a bit like reading genealogy. It’s confusing, but if you dig deep enough there are a lot of interesting characters.

The British monarchy retains a bit of fascination for Americans. Members of the British royal family are original examples of being famous for being famous. We all loved Princess Diana (and we still do), yet as Americans it is not in our DNA to revere royalty.

Some friends shared an interesting example of the difference in British and American views. They had seen the stage play Hamilton three times, including once in London. In the play, Jonathan Groff’s Tony-nominated performance as King George III delights audiences in America even before he opens his mouth. (Other actors playing the role emulate his performance.) The king is a character of comic relief, and gets great laughs in America.

When the king walked onto stage in London, you could hear the proverbial pin drop. Admittedly, the lyrics the King George III sings, to music that calls to mind the Beatles’ Penny Lane, are dark, but they are brilliantly funny. There was not a single laugh as the actor sang, for example,

“Oceans rise, empires fall

We have seen each other through it all

And when push comes to shove

I will send a fully armed battalion to remind you of my love!

Da-da-da, dat-da, dat, da-da-da, da-ya-da…”

It is no surprise that the website The Royal Family at royal.uk is very positive and respectful (respectful of some; it seems that Harry and Meghan have been cropped out of the family photos). There is a section on history, but you need to find your way to the historic royals, then click through each person one by one. Then you need to read between the lines.

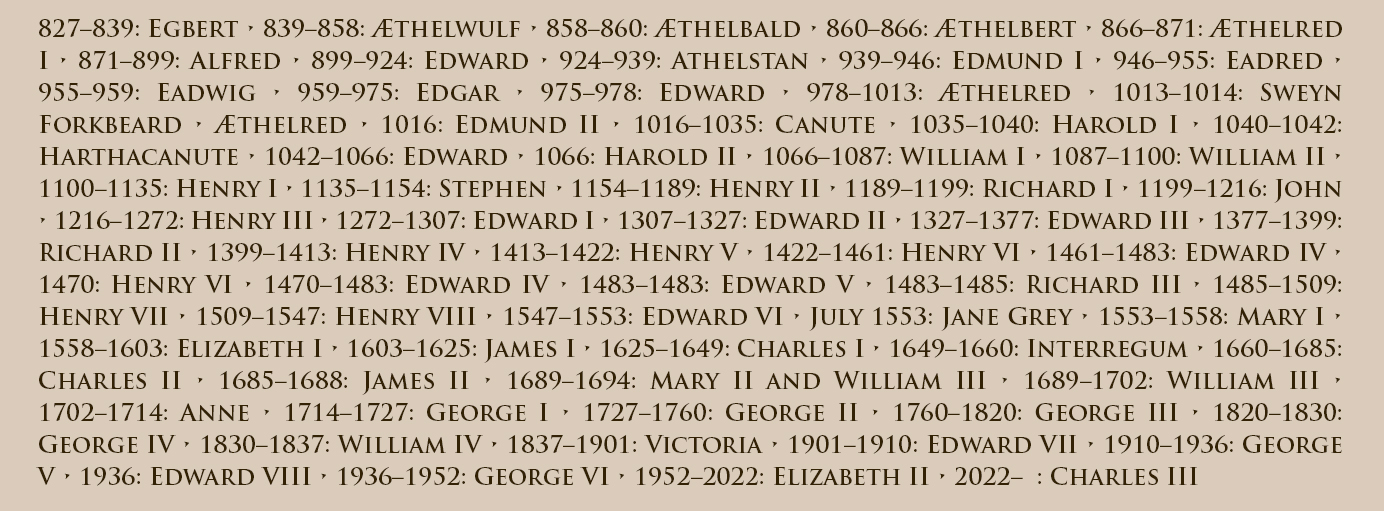

As I began writing my novel about American history (two years ago—still writing), I compiled a list of English monarchs that was both descriptive and concise to keep track of dates and people. I then expanded the list back to Egbert, and then to pre-history, because why not?

Here is a quick romp through the Kings and Queens of England, and then of Great Britain, and a bit of pre-royal history. I’ll slow down for those who impacted the formation of America, beginning with the magnificent Elizabeth I, whose reign led England to be powerful enough to colonize America.

Pre-history

12,000 BCE With the end of the Ice Age, Homo Sapiens replaced Neanderthals as the dominate species in the land that will become Britain.

6000 BCE Rising sea levels formed the English Channel, separating the British Isles from the European continent.

3100 BCE Stonehenge was built in its original form, about five centuries before the first known pyramid in Egypt. Newgrange, a passage tomb aligned to the winter solstice, was built in Ireland about a century before Stonehenge.

700 BCE Celtic people began to colonize the British Isles.

55 BCE Romans under Julius Caesar began raiding the British Isles.

43-410 After a century of raids, the Romans conquered the the land that would become England (but not the future Scotland). Roman occupation began under Emperor Claudius and lasted about 400 years.

122 Emperor Hadrian ordered a wall built on the Scottish Border. (What could not be conquered was walled out.)

450–550 Forty years after the Romans left, the Anglo-Saxons arrived. They never conquer Wales, Scotland, or Cornwall, but ruled most of the land, which they divided into seven kingdoms. They ruled until the Vikings arrived. (The Anglo-Saxons were Angles, Frisians, Saxons, and Jutes— tribes of Germanic people who originally came from the area of current northern Germany, northern Holland, and Denmark).

460 St Patrick arrived to bring Christianity to Ireland.

597 St. Augustine arrived from Rome and began Christian conversion of the Anglo-Saxons.

827–1013: Early Saxon Kings

827–839 Egbert conquered other British kingdoms, and was the first to establish stable rule over all of Anglo-Saxon England.

839–858 Æthelwulf successfully fought the Vikings. He travelled with son Alfred to Rome to see the Pope in 855.

858–860 Æthelbald forced his father to abdicate upon his return from Rome. Æthelwulf then died, and Æthelbald married his widowed stepmother, Judith. The marriage was annulled after a year because, even then, people said, “Ewww…”

860–866 Æthelbert, son of Æthelwulf, succeeded his brother and had his rule complicated by the arrival of the Viking “Great Heathen Army.”

866 – 871 Æthelred I, another son of Æthelwulf, fought the Danish Army, beginning a family tradition.

871 – 899 Alfred, known as Alfred the Great, was the son who travelled with Æthelwulf to Rome. He secured a few years of peace with the Danes, and established Christian rule over most of England.

899 – 924 Edward, known as Edward the Elder, was son of Alfred the Great.

924 – 939 Athelstan, son of Edward the Elder, defeated a combined army of Scots, Celts, Danes and Vikings to claim the title of King of all Britain.

939 – 946 Edmund I succeeded his half-brother at age eighteen, already having been to war. He re-established Anglo-Saxon rule in the north after another rule by Scandinavians. Was killed by a robber at age twenty-five, leaving two sons who were too young to rule.

946 – 955 Eadred was the third son of Edward the Elder to rule in a row. He also defeated Norsemen, sending the final Scandinavian King of York, Eric Bloodaxe, packing. He died without issue.

955 – 959 Eadwig, elder son of Edmund I , became king at age sixteen, succeeding his religious uncle. He was known for his personal indiscretions. (The bishop apparently complained that he had to pull the teenager from bed for his coronation. He wasn’t sleeping, but rather in the embrace of two women—a mother and daughter. The new king exiled the bishop.) Eadwig died mysteriously at age twenty.

959 – 975 Edgar, younger son of Edmund I, succeeded his brother as teenage king. Known as Edgar the Peaceful, he recalled the bishop and made him Archbishop of Canterbury. He met and formed an alliance with six kings of Britain (including the King of Scots, the King of Strathclyde, and four Princes of Wales).

975 – 978 Edward, known as Edward the Martyr, succeeded his father, Edgar, to become king at age twelve. Supporters of his younger half-brother murdered King Edward when he was just fifteen. (This was well over a thousand years ago, but it still hurts. Poor Edward.)

978 – 1013 Æthelred, Edward’s little half-brother, was known as Æthelred the Unready, because he became king at age ten. (Notice that Edward is still a popular name, yet you’ve likely never met an Æthelred? Small consolation, but still a bit.)

House of Denmark / Wessex / Denmark / Wessex / Godwin

1013 – 1014 Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark overthrew Æthelred at Christmas time, 1013. The Viking raids had begun over 200 years earlier and Danish Vikings occupied Northumbria beginning in 865. Alfred had agreed to a Danelaw treaty of Vikings controlling the north, and Anglo-Saxons controlling the south. Æthelred ordered a massacre of Danes in 1002, and Sweyn’s sister Gunhilde was killed. Sweyn had his revenge, overthrowing Æthelred, but he died five weeks later.

1014 – 1016 Æthelred (now ready) returned when Sweyn Forkbeard died within weeks (restoring the House of Wessex for the first time). Æthelred constantly kept an eye out for Sweyn’s son Canute.

1016 Edmund II, known as Edmund Ironside, succeeded his father, Æthelred. Following a defeat in battle, Edmund agreed to share control with Canute, then promptly died.

1016 – 1035 Canute, known as Cnut the Great or Canute the Dane, son of Sweyn and Gunhilda, restored the House of Denmark and ruled for nineteen years. Legend says he once ordered the tide not to come in to prove to his subjects that a king was not a god.

1035 – 1040 Harold I was an illegitimate son of Canute. Harold Harefoot seized power while the legitimate heir was off fighting in Denmark.

1040 – 1042 Harthacanute was returning to invade England, with an army of Danes, when his half-brother Harold I died before he could kill him. Harthacanute had Harold’s body dug up, beheaded, and thrown into the Thames River. That’ll show him.

Harthacanute’s mother, Emma of Normany, had been married to Wessex King Aethelred (Unready, then Ready Enough) before she married Danish King Canute. Harthacanute’s older half-brother Edward of Wessex was exiled in Normandy. Promoting family unity (at least with his mother’s son; recall he beheaded the corpse of his father’s son), Harthacanute invited Edward back. Harthacanute promptly died, while drinking a toast at a wedding—nothing suspicious about that. He was the last Danish King to rule England.

1042 – 1066 Edward, known as Edward the Confessor (a religious man), was son Æthelred. He restored the rule of the House of Wessex a second time. He reigned twenty-four years, then died childless.

1066 Harold II, known as Harold Godwinson because that was his name, was elected king. He was supposedly named heir by Edward. He had no royal bloodline, and was the sole member of the House of Godwin.

House of Normandy (Norman Kings)

1066 – 1087 William I, the Duke of Normandy, incensed over the election of commoner Harold, claimed that Edward, as second cousin on his mother’s side, had promised him the throne. (Not following? No worries. We’ll move along quickly.) William attacked. Harold died at the Battle of Hastings, ending his brief reign, and the reign of Anglo-Saxon Kings. William the Conqueror, also known as William the Bastard (no kidding), ruled twenty years until he died from a fall from his horse in battle.

1087 – 1100 William II, aka Rufus, succeeded his father. He was known for his cruelty during his nearly thirteen year reign, and was “accidentally” killed by a stray arrow while hunting.

1100 – 1135 Henry I, called Lion of Justice, followed his brother William II. He ruled thirty-five years, and was to be succeeded by his daughter Matilda. (Her brother—males were always chosen first—drowned in the sinking of White Ship. Henry I named his daughter as his successor.)

1135 – 1154 Stephen was Matilda’s cousin (and William I’s grandson). He seized control because Matilda was, well, female. He turned out to be (and this isn’t a feminist reinterpretation) a really terrible king, with England experiencing regular raids by the Scots and Welsh, and a civil war, called The Anarchy, that lasted much of his eighteen-year reign. Matilda did control England for seven months in 1141, but was never actually crowned. A compromise was reached that Matilda’s son would succeed Stephen the Simp (kidding this time, actually Stephen of Blois).

House of Anjou/Plantagenet

1154 – 1189 Henry II, known as Henry of Anjou, was the son of Matilda and Geoffrey Plantagenet (grandson of Henry I). He married Eleanor of Aquitaine, giving him control over land in France, then expanded the holdings as a brilliant soldier.

1189 – 1199 Richard I was Henry II’s son and was known as Richard the Lionheart. He spent a total of about nine years of his nine-and-a-half year reign abroad fighting in the Crusades. The Crusades were wars to end Islamic rule of Jerusalem and the Holy Lands. (On his way home from Palestine during the Third Crusade, he was captured and held hostage. The ransom nearly bankrupted his country.)

1199 – 1216 John Lackland succeeded his brother, Richard. He reigned seventeen years and was unofficially nicknamed John the Worst King Ever.

1216 – 1272 Henry III succeeded his father and served fifty-six years, beginning at age nine. He started the House of Commons, but not in the noble, let’s share power, kind of way. He was captured and forced. Nonetheless: Parliament.

1272 – 1307 Edward I, known as Edward Longshanks (he was tall), succeeded his father and actually formed the Parliament. He then defeated Welsh chieftains to rule over England and Wales, naming his eldest son Prince of Wales. Then he went after Scotland and was known as Hammer of the Scots. They’re not too fond of him. He died while on the way to fight Robert the Bruce, who became King of Scotland. (You may note he was the third King named Edward, but is nonetheless called Edward I because the Plantagenets didn’t count the Normans.)

1307 – 1327 Edward II followed his father. After nineteen years he was both deposed and murdered.

1327 – 1377 Edward III followed his father. He was crowned at age fourteen and reigned fifty years. His reign included the 1348–50 bubonic plague, aka the Black Death, that killed half England’s population (not his fault) and the Hundred Years War with Scotland and France (probably his fault).

1377 – 1399 Richard II was grandson of Edward III. His father, who later was called Edward the Black Prince, died the year before his grandfather. Richard II was crowned at age ten. Richard became unhinged, was deposed, and then was murdered. (See Shakespeare, William: “Richard II.”) And moving along…

House of Lancaster / House of York / House of Lancaster / House of York

1399 – 1413 Henry IV, another grandson of Edward III by John of Gaunt, seized power from his cousin. (He was not of Matilda’s Plantagenet family; the House of Lancaster was named for the Earldom of Lancaster.)

1413 – 1422 Henry V followed his father. He was still fighting his great-grandfather’s Hundred Years War. (They obviously weren’t so pessimistic as to name it that at the beginning.)

1422 – 1461 Henry VI was crowned as an infant. He was the only English monarch also crowned King of France, but he was only ten years old at the time; it wasn’t for his accomplishments. (Charles VII was already holding the throne.)

The Hundred Years War was still going; perhaps his marriage could achieve peace, at least with someone. Imagine the predicament of this shy pacifist: It was first planned that he would marry a Scottish princess at age thirteen, but he didn’t. Then he was to marry a French princess (the daughter of King Charles VII, which was problematic as he would have to renounce the crown his father-in-law wore). How about a German princess instead? No? The daughter of the Count of Armagnac? Nope. By now he was twenty-one and wouldn’t “swipe right” without seeing a portrait. Rather than marry Charles VII’s daughter, how about his niece, Margaret? She was said to be a looker—and at barely fifteen she was already stronger than her twenty-three-year-old groom. She may be how he lasted thirty-eight years, despite mental instability. He was deposed during the War of Roses, by Edward IV, of the House of York.

The War of Roses had nothing to do with florists, or ever flowers. The symbol for the House of Lancaster was a red rose; the symbol for the House of York was a white rose.

1461 – 1483 Edward IV (House of York) was great-grandson of Edward III. He ruled until Henry VI regained the throne.

1470 Henry VI (House of Lancaster) was back, then murdered in the Tower of London, truly ending his reign this time. (He was murdered the day after his son was killed in battle, deleting a stronger potential successor.)

1470 – 1483 Edward IV (House of York) exclaimed, “I’m back!” Nobody liked him much; nonetheless his two reigns, combined, lasted twenty years.

1483 – 1483 Edward V followed his father as king, at age twelve. He was assumed murdered two months later, along with his brother (the Princes in the Tower), by his evil Uncle Richard.

1483 – 1485 Richard III was brother to Edward IV and uncle to the shortest-lived monarch in English history. (How did John manage to get the nickname Worst King Ever with Richard III, murderer of nephews, in the mix? Because Richard was killed in battle after only two years damage; John ruled for thirteen years.)

House of Tudor

1485 – 1509 Henry VII, as Richard III’s third cousin once removed, was an unlikely successor. However, Richard III was killed in battle. The crown was picked up off the ground (or removed from his still-warm body) and placed on the head of Henry Tudor, who was henceforth Henry VII. Henry VII was a Lancaster by virtue of descending from Edward III. Henry’s royal line came through his mother, which was unusual. (Her grandparents married twenty-five years after their son was born, further complicating the legitimate line of succession.) Henry VII won the crown on the field of battle, the last English monarch to do so. After seizing the crown, he married Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV, uniting the warring Houses of Lancaster (red rose) and York (white rose).

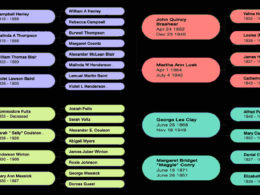

How did Henry happen to conveniently marry Elizabeth? First, Elizabeth had been betrothed at ages three and five, but the political reasons collapsed leaving her an unmarried six year old. After her uncle, Richard III killed her brothers (see Princes in the Tower, above), the evil uncle wanted to marry her. That was really too horrid, so Elizabeth’s mother plotted with Henry’s mother (in a pact that gives a good connotation to conniving). Elizabeth married Henry. Elizabeth was daughter, sister, niece, wife, and mother to English kings.

Fun aside: Playing cards were invented during Henry VII’s thirty-eight year reign; there is a legend that the Queen card portrait is Elizabeth of York.

American connection: Henry VII commissioned John Cabot (born Zuan Chabotto in Venice) to explore the coast of North America in 1497—the first European exploration of North America since the Norse visits in the eleventh century. This gave England some claim among European nations to the North American land north of Florida. Florida was already claimed by Spain.

1509 – 1547 Henry VIII, son of Henry VII, founded the Church of England and made himself head of it to obtain a divorce. He also made himself king of Ireland. Despite his infamous quest for a male heir, he did have a son from wife number three (of six), Jane Seymour.

1547 – 1553 Edward VI became king at age ten, as Henry VIII’s son. He died at age sixteen, likely from tuberculosis. In his will (What sixteen-year old has a will? A king.), he chose his cousin Lady Jane Gray as his successor.

July 1553 Jane Grey was a committed Protestant, chosen because she would support the Church of England founded by Henry VIII. Being chosen was actually a very bad thing for sixteen-year-old Jane. She had a busy summer in 1553: She married in May, was nominated as queen in her cousin’s will in June, was proclaimed queen on July 10, then, as support for Edward VI’s half-sister Mary grew, she was deposed after nine days as queen. As a usurper, she was charged with high treason and imprisoned. She and her husband were both beheaded the following February. (Jane, bless her heart, is a “disputed claimant.” She is listed as queen in some charts and not in others.)

1553 – 1558 Mary I, the daughter of Henry VIII attempted to restore England to Catholicism. Poor Jane Grey wasn’t the only one who died; other Protestants were burned at the stake. Mary I earned her nickname: Bloody Mary. (Yes, the drink is named for her.) She married Philip, King of Spain, at age thirty-seven, but remained childless. He was co-ruler under their marriage treaty. She died at age forty-two and was succeeded by her half-sister.

1558 – 1603 Elizabeth I was known as the Virgin Queen (she never married). She was daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. She ruled successfully for forty-five years. She was a popular sovereign. She introduced Elizabethan Poor Laws to help people. English literature flourished during her reign and Shakespeare was at the height of his popularity. As a crowning achievement (so to speak): Elizabeth oversaw the victory over the Spanish Armada. (On the negative side of the ledger, she had her cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, imprisoned for many years. Mary was convicted of treason and executed.)

American connection: The first American colony was named Virginia for her, by Walter Raleigh. The English victory over the Spanish Armada likely changed the course of American history.

House of Stuart

1603 – 1625 James I was grandson of Henry VIII’s elder sister Margaret sister and the son of beheaded cousin Mary. He was heir apparent as the Virgin Queen was obviously childless. (No judgments about her personal business, but if a baby had come along they surely would have changed her nickname.) James was conveniently Protestant. He had already been King James VI of Scotland for thirty-six years—so what war couldn’t achieve, right of succession did, sort of. England and Scotland were both ruled by James I. Known as a scholar, rather than a man of action, he commissioned an authorized version of the Bible.

American connection: The James River and Jamestown were named for James I. The Puritans weren’t please with an “authorized” Bible, and were furthered inspired to leave on the Mayflower.

1625 – 1649 Charles I succeeded his father. He believed in the divine right of kings, therefore he ruled by divine right. What could possibly go wrong? He decided he didn’t need Parliament and pretty much abolished it. Then there were civil wars, in Scotland in 1637, in Ireland in 1641, and England beginning in 1642.

During the English Civil War, his Royalist forces were defeated by Oliver Cromwell. Charles I was tried for treason. The Parliament he abolished? They abolished him. (He was beheaded on January 30, 1649.)

American connection: Charles I granted a charter to Catholic Cecilius Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore, for what was to become the Maryland Colony, a proprietary colony for Catholic settlement. (The colony may have been named for Charles I wife, Henrietta Maria of France, although she was likely named for the mother of Jesus.) Lord Calvert himself never visited America, but his brother Leonard was an early settler and governor. Many Maryland settlers were distressed when Charles I lost power.

The Commonwealth / The Interregnum

1649 – 1660 There was no monarch after Charles I was beheaded. Britain was declared a Commonwealth, and ruled by a Rump Parliament. (Seriously, it was called The Rump. The Rump did such things as impose a death penalty for adultery.) Oliver Cromwell then became Head of the Commonwealth. He believed God was on his side. (It’s unlikely that he appreciated the irony that Charles I also thought God was on his side.) A converted Puritan (and the converted are often the most observant), Cromwell closed all the music halls and banned Christmas celebrations—a good time was had by all, or maybe not so much. He also expelled Parliament, because England had him, what more could they need?

Then there was the Irish genocide. Not many rulers pull off such atrocities, much less when power moves to the next generation. When Oliver Cromwell died (of natural causes) his son Richard couldn’t maintain support. Richard Cromwell resigned, fleeing to France.

American connection: The Puritans were supporters of Cromwell, and were distressed when his son lost power. In Virginia, the Royalists bided their time, and got along well enough with the Puritan governor, until the monarchy was restored.

1660-1649: The Stuarts, again

1660 – 1685 Charles II was restored to the monarchy as King of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. After Cromwell, Parliament said, “You can return now; jolly good.” Known as the Merry Monarch, Charles had a wife and thirteen known mistresses.

American connection: Charleston was named for Charles II. Charles II spent much time undecided during Bacon’s Rebellion. In 1672, Charles II encouraged the Royal Africa Company (RAC) to expand their slave trade; the RAC sent tens of thousands of enslaved people to the Americas during his reign.

1685 – 1688 James II was brother of Charles II. (Charles II left many children, none legitimate.) James had converted to Catholicism, but Uncle Charles (who was king and could insist) had his two surviving children, Mary and Ann, raised as adherents to the Church of England.

After his first wife died, James married Catholic Mary of Modena. Mary’s eleventh pregnancy produced the first child to survive infancy, James III, who was rumored to be a substitute smuggled in for another stillborn child. Either a Catholic successor or a fake successor was reason enough for a “Glorious Rebellion.”

American connection: James II was the leading investor in the Royal African Company (and subsequent Royal African Company of England—RACE), which shipped more kidnapped and enslaved Africans to the Americas than any other institution. Some enslaved people were branded DY for Duke of York.)

1689 – 1694 Mary II and William III (both Protestants) were invited by Parliament to invade. Mary was the aforementioned older daughter of James II. She had married William of Orange eleven years earlier, when she was fifteen (after crying for two days). William was a Dutch prince and her cousin, himself fourth in line to the throne. James II fled and was considered as abdicating; his daughter and son-in-law reigned as William and Mary.

American connection: William and Mary College was named for the two of them. Williamsburg, the second capital of Virginia, was named for him.

1689 – 1702 William III, aka William of Orange (Prince of Provence), aka William II of Scotland, aka King Billy, ruled alone after Mary’s unexpected early death (at age thirty-two from smallpox). They had no children.

In 1701 Parliament passed an act that no Roman Catholic, nor anyone married to a Roman Catholic, could hold the English Crown.

1702 – 1714 Anne was Mary’s sister, and ruled for twelve years. During her reign, the United Kingdom of Great Britain was created by uniting England and Scotland. Of Anne’s seventeen pregnancies only one child, William, survived. William died of smallpox at age eleven. After Anne’s death, the succession went to the nearest Protestant relative of the Stuart line. This was Sophia, granddaughter of James I by his only daughter, Elizabeth of Bohemia. Sophia died shortly before Ann did, so her son George became King.

The Hanoverians

1714 – 1727 George I never learned to speak English. The fifty-four-year-old new king reportedly arrived with eighteen cooks and two mistresses. He relied on Robert Walpole, Britain’s first prime minister, to run the country.

1727 – 1760 George II was a bit more English than his father, but still relied on Walpole to govern. The Jacobites (supporters of James II and the Stuart dynasty) attempted to restore James II’s son, Charles Edward Stuart, a.k.a. Bonnie Prince Charles as king. They failed.

1760 – 1820 George III was the English-born grandson of George II. He was king for over fifty-nine years. At the time, he was the longest reigning British monarch. Due to his health problems, his son ruled as Prince Regent for the last decade of his six-decade rein.

American connection: George III was king during the American Revolution, and as thus he was the last monarch who reigned over the American colonies.

1820 – 1830 George IV succeeded his father by being the eldest of his fourteen surviving children. George IV was notable for his love life. He illegally married Maria Fitzherbert, a twice-widowed commoner whose Catholicism would have disqualified him for the throne. Their relationship continued after he married his cousin, Caroline of Brunswick. After a year of marriage, he told her to go away and do as she liked, and she liked dancing topless in public. The prince had her called before the House of Lords for adultery, and she did seem to flaunt her affairs, but she was able to avoid a divorce. When George IV became king, he excluded her from his coronation, despite her banging on the door. Their only child, Charlotte, died before the king did, so he had no legitimate heir.

1830 – 1837 William IV, third son of George III, was sixty-four when he succeeded his brother as king. He was known as the Sailor King as he had served in the Royal Navy in his youth (as younger sons did). After the death of his niece, Princess Charlotte, he had moved up in the line of succession. He then married for the first time in order to sire a legitimate heir—despite having ten children by his twenty-year relationship with Dorothea Bland (a.k.a. the actress Mrs. Jordan). His twenty-year marriage to Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Coburg Meiningen was apparently faithful and happy, although their two daughters died young, leaving no heirs.

William IV, regardless an inauspicious background and short tenure, had an admirable reign. He was hardworking and approachable. He respected Parliament, seeing it as his duty to state his opinion and allow them to rule. During his reign, slavery was abolished in the English colonies, despite previous opposition from the House of Lords; the Factory Act of 1833 was introduced to enforce restrictions on the use of child labor; and the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 was passed to help the destitute. William was criticized both for going too far with reforms and for not going far enough.

American connection: As a young Navy man of fifteen or sixteen, Prince William Henry served in New York during the American War of Independence, becoming the first member of the royal family to set foot in America. (General Washington approved a plot to kidnap him, but efforts were unsuccessful.)

America was poorly served by Charles II and James II in their promotion and support of the Royal African Company of England and the Atlantic slave trade. However, with the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 under William IV, the young United States may have been better off in some ways if the revolution had not been successful.

1837 – 1901 Victoria succeeded her uncle. William was fond of her, and expressed the wish to live long enough that she come of age and her mother not be a regent. He succeeded and Victoria was crowned two months after her eighteenth birthday. She reigned for over sixty-three years, the longest reigning monarch until surpassed by her great-great-granddaughter, Elizabeth II. During her reign, the British Empire doubled in size and reached its peak as a world power.

Victoria married her first cousin Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Theirs was a love match. She mourned for decades after his 1861 death from typhoid fever. She wore black for forty years. The marriages of some of their nine children into other royal families earned Victoria the title Grandmother of Europe.

The House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and the Windsors

1901 – 1910 Edward VII was second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria. His charm and French language skills helped improve relations with France; his relationship with his nephew German emperor William II was not as friendly.

1910 – 1936 George V succeeded his father, Edward VII. He was in his mid-twenties and in the navy (as a second son) when his elder brother died of pneumonia and he became heir apparent. He left the navy to prepare for his future role, and married his brother’s former fiancée. He changed the royal family’s official name to House of Windsor (after the castle, not vice-versa) in 1917, likely due to anti-German sentiment. He was king during World War I.

1936 Edward VIII succeeded his father, George V. Rumors of his affairs with married women were merely causes for concern, until his marriage proposal to one threatened a constitutional crisis. The British monarch is titular head of the Church of England, and the church opposed remarriage of a divorced person if the former spouse was still alive. After she divorced, American Wallis Simpson had two living former husbands. Edward VIII abdicated the throne after a reign of less than a year and married her. After resigning, he continued to court controversy as the couple met with Adolf Hitler.

1936 – 1952 George VI succeeded his brother and was a popular king. He, his wife (later known as the Queen Mum), and their two daughters remained in Buckingham Palace when it was bombed during World War II. George VI had lung cancer when he died at age fifty-six. (King James I famously hated tobacco, thought it was unhealthy, and attempted to suppress the expansion of its growth and use.)

1952 – 2022 Elizabeth II succeeded her father and was crowned at age twenty-four. The fortieth monarch since William the Conqueror, she was the longest serving British monarch in history. For more than a century before her reign, since William IV, British monarchs served and influenced, rather than ruled. During her seven decades on the throne, the changes in the society made the monarchy seem an old-fashioned notion. . . until the world fell in love with her daughter-in-law, Princess Diana. She was beloved both for her great personal charm and her humanitarian work.

2022– Charles III was the oldest person, at age 73, to accede to the British throne when he succeeded his mother. He had been heir apparent for seven decades. In 1981, at age 33, he married 20-year-old Diana Spencer, who was lovely and appropriately chaste enough to be a future queen. Many future monarchs had political marriages (recall that Mary cried for days before marrying William), but this one seemed particularly cruel in that Diana was led to believe it was a marriage of love. They divorced after fifteen years, and Diana died in a car crash in 1997. Nearly a decade after his divorce, Charles married Camilla Parker Bowles, the woman he had been in love with all along. (Diana had famously said, “There were three of us in this marriage, so it was a bit crowded.”) The mores that caused his great uncle, Edward VIII, to abdicate no longer applied.

Charles could have chosen another name when he became king, but it seems his lifelong use of Charles (a great name) overcame the connection to Charles I, a much-less-than great king. Charles and Diane’s son William is now heir apparent.