Genealogy websites all contain some false information and wishful thinking, but researching the connections can still be fascinating.

Cecily Bayley Jordan Farrar arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, around 1611, as a ten-year-old child traveling alone. By the time she was twenty-five, she was married to her third husband and a wealthy woman. She is one of the ancestors who inspired me to write History with a Southern Accent.

Cecily has thousands of direct descendants. Perhaps you are one of them. I am not, although I thought I was for a decade.

Genealogy and Family

I have been interested in family history and genealogy—tracing lines of descent—for over fifty years. I never questioned why I was so interested until I began writing about it. Many cultures revere ancestors, some to the extent of ancestor worship. My culture is American of English/Scots-Irish descent. If I revere my ancestors, it’s not because it’s in my genes.

When I was a young teenager, my father and I would discuss nature versus nurture, heredity versus environment. He wanted to decide which one dominates, and he leaned toward heredity; I thought both were relevant. (This was long before I knew of epigenetics and myriad ways environment can change gene expression, which further complicates the question.) My father was interested in animals as well as people, and bred dogs to enhance positive traits. In recent years, I noticed our Spanish water dogs, generations removed from their traditional roles as sheep herders and water retrievers, would herd their people, were suspicious of potential wolves, and were natural swimmers. One would guard doorways and look for a cave during thunderstorms. The other moved his legs in swimming motion whenever his belly got wet in the shower.

I always wondered what makes people who they are, and what we can rightly expect from our fellow humans. I have a positive attitude and care deeply about other people. I didn’t work to develop those character traits, they came naturally to me. I sympathize with people who are always negative, reasoning that it must come naturally. After each of my sons was born, I marveled at how much of their temperament was innate.

Is personality written in our genes? If so, who were these people—people we never met—who are influencing our very beings?

Fiction can often illuminate truth more clearly than fact can. In Pulitzer-Prize winning novelist Anne Tyler’s book French Braid, a man notices that his grandson’s mannerisms evoke the child’s great-grandfather, even though the two never met. He thinks of the ripples that remained in his daughter’s hair after her braid was released, and tells his wife,

“That’s how families work, too. You think you’re free of them,

but you’re never really free; the ripples are crimped in forever.”

Researching genealogy, the early days

Back when I began researching family history, the procedure was for someone in a family to write to the interested older person in the family (or extended family), and tell her (it was typically a woman) there was finally another person interested in the family history. She would send a letter with what she knew. I kept those old letters I received, and now, many years later, I am that “interested older person” who cares about family history.

The information we had was obtained from oral history, old family Bibles, census records, letters, legal documents such as wills, land records, and pension records. (Revolutionary War soldiers or widows who lived until the 1830s could apply for pensions, for example.)

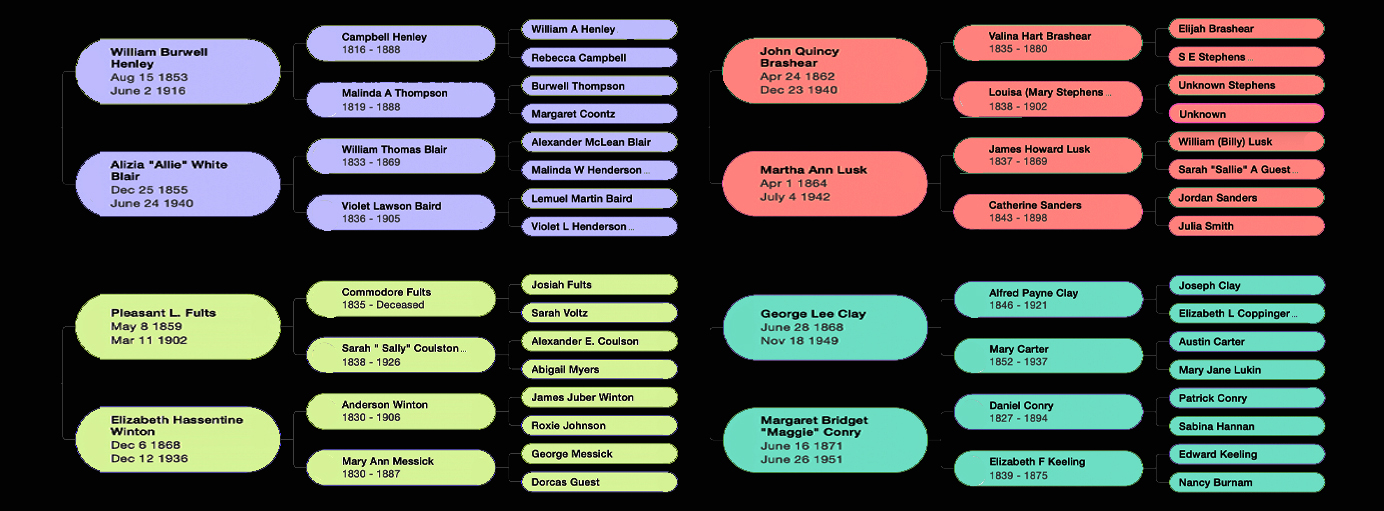

One intriguing ancestor, whose history I continually sought, was the father of my mother’s Grandma Brashear. James Lusk was described in the family Bible by one word: “Indian.” As for the Brashears, I read: “Valina Hart Brashear came from France. He was a school teacher who died while teaching near Oak Grove in Franklin County, Tennessee.”

Quote from The History of Pelham [Tennessee] Methodist Church.

How did a Frenchmen become a rural Tennessee schoolteacher in the early 1800s?

My maternal grandfather’s family history was more straightforward: William Alexander Henley was English Episcopalian and arrived in Tennessee from Virginia before 1812. His grandson married Allie White Blair, who was Scots-Irish.

My most distant ancestor for whom I heard passed-down oral history was Burwell Thompson, five generations back. He came from Wales (except he didn’t actually), fought in the Revolutionary War, and was “an old widower” with three children when he came to Tennessee, remarried, and had two more children. His daughter had twelve children, one of them my great-grandfather who had five children. My grandfather had eight children, and as of 2020 has over 200 descendants. It’s easy to realize that my Burwell Thompson may easily have over 1,000 descendants. It gives me a sense of strong connection to think about this, and I hope it does the same for you.

On my father’s side, I was most interested in my grandmother Hassie Clay’s ancestors, as my father was named Clay. In my junior high school history class, I became convinced we were related to Senator Henry Clay. My father knew that his people were mostly Irish and English, although our Fults name (Volz in the 1700s) was German.

In the 1970s in Nashville and the early 1980s in Seattle, I visited reserve sections in libraries with nickels in my pocket. If I found anything promising in the old census records, I could put a nickel in the copy machine and keep a copy of the record. I found William Henley, but no wife’s name. I found Burwell Thompson. I found several James Lusks, including one who escaped the Confederate army and moved to Minnesota. Intriguing, but not my James Lusk.

By the early 1990s, I found the microfishe records kept at a Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Center in Delaware. Microfische were state-of-the-art for research at the time. They are pieces of film containing microphotographs of the pages of documents. Being so small, a center could store copies of many records on these flat films. The films looked like x-ray sheets, and could be viewed in enlarging lightboxes. I could search through Tennessee census records while in Delaware.

Why a Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (aka Mormon) Center? As explained on the website https://newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org/topic/genealogy:

“Latter-day Saints believe families can be together after this life. Therefore, it is essential to strengthen relationships with all family members, both those who are alive and those who have died. Latter-day Saints believe that the eternal joining of families is possible through sacred sealing ceremonies that take place in temples. These temple rites may also be performed by proxy for those who have died. Consequently, for Latter-day Saints, genealogical research or family history is the essential forerunner for temple work for the dead. In Latter-day Saint belief, the dead have the choice to accept or reject the services performed for them.”

I remember holding my breath as I came upon a record that included a name for William Alexander Henley’s wife. His wife’s name — I finally discovered — was “Mrs. William Henley.” I also found there was a William Henley who was the son of Elizabeth Dandridge. The Dandridge name was familiar: Elizabeth was sister to Martha Washington. The location was right and the dates were almost right. Close but not quite.

Researching genealogy in the internet age

Ancestry.com, available as a subscription service beginning the late 1990s, was a game changer. In those early days, I was too busy building my own descendancy line (raising two sons, while also working for a living as a graphic designer) to play with the new tools. When I did, I was amazed.

By the way, Ancestry.com was developed from Latter-day Saints’ research. The LDS Church remains a leading resource for genealogists. I would recommend that anyone beginning, or just casually interested, start with FamilySearch.org. It is available online at no cost. You don’t build your own tree as you do with other sites, but you can find others research on your ancestors and add notes. There are certainly errors, but their goal is accuracy and they welcome input.

By the early 2000s, I had input my former research and discovered, with a few clicks, that Mrs. William Henley’s given name was probably Rebecca Campbell. The name came from an old cemetery record, so seemed trustworthy. There was no more on Rebecca, but I had a name.

Lots of information, some of it true

In several weeks I had lots and lots of names and charts. I had names in the Brashear line going back to King Charlemagne, with only two or three links that were clearly impossible.

It turns out that in genealogy, as in most things on the internet, there is a good bit of false information. This brings to mind the great Mark Twain quote:

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble.

It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

Perhaps the most interesting thing about that quote, which pops up regularly online, is that there is no evidence that Mark Twain ever wrote or said it.

The Center for Mark Twain Studies tracts the quote history to 19th-century American humorist Josh Billings, including a line in his 1886 complete works, “I honestly believe it is better to know nothing than to know what ain’t so.” Versions were regularly repeated by humorists of the time.

Walter Mondale said, in a 1984 presidential debate with Ronald Reagan, “Well, I guess I’m reminded a little bit of what Will Rogers once said about Herbert Hoover. He said, ‘It’s not what he doesn’t know that bothers me, it’s what he knows for sure that just ain’t so.” The quote became most regularly attributed to Twain after it was, and this is further irony, used with a Twain attribution in Al Gore’ documentary, “An Inconvenient Truth.”

Source: Matt Seybold, “The Aprocryphal Twain: ‘Things we know that just ain’t so.’ ” The Center for Mark Twain Studies, October 2016. Posted at https://marktwainstudies.com/the-apocryphal-twain-things-we-know-that-just-aint-so/

An example of what was known for sure of my great-great grandfather Brashear:

1) Valina Brashear came from France. In truth, he was born in Alabama in 1835. But his grandfather did immigrate to Alabama—from North Carolina. Their ancestors were French, although they immigrated to Virginia from England a full two centuries before Valina was born. It’s fascinating to me that Valina maintained his ancestral connection to the French Huguenots, as he must have done for people in his community say he was French. As I often find the case, the truth is more interesting than the myth.

2) Valina Brashear died while teaching school. That part I believe. Heart disease was common among the Brashears.

Most errors in genealogy records are not deliberate. Someone finds a connection that looks feasible, and then documents that person as the ancestor they are looking for. The name, place, and dates seem too close to be coincidence.

However, many families I have researched have used the same given names multiple times, even in the same generation, regularly among cousins, and even occasionally among siblings. Sometimes a connection is misattributed because of the same name, other times a connection is rejected because it seems improbable that two siblings have the same name. Miss-links often occur outside family lines, as well. (I could give many examples, none very interesting.)

Inventing a human

I discovered the creation of a person. My ancestor Solomon Sanders’ youngest son (also my ancestor) was born when Solomon was seventy-six-years old. (His wife was much younger.) In Solomon’s Revolutionary War pension application, he stated

“My occupation has always been that of a farmer which I am not now able to pursue; my family consist of a wife named Mary aged about 54 years, a daughter named Nancy aged about 18 years, a daughter named Sally aged about 16 years and two sons, to wit, Jacob aged 12 years and Jordan aged 11 years, all of whom are dependent on me for support.”

Please note “two sons, to wit, Jacob aged 12 years and Jordan aged 11 years.” In the handwritten words to wit, there are large Ts and a short i. A descendant researcher, perhaps unfamiliar with the term to wit, which means namely, misread the handwritten “TowiT” to be “Tom T.” She concluded that Tom T was Solomon’s son, and the father of Jacob and Jordan. Tom T Sanders now appears on several genealogy websites.

Over time, and with time-consuming double-checks, I built trees with many ancestors. A few of the links I quickly accepted I later discovered were false, and one or two I rejected as false I now believe are true.

Despite multiple William (and Leonard) Henleys, I thought I found my William Henley, mentioned above. He was cousin to Elizabeth Dandridge Henley’s son. (However, I have recently communicated with another descendant who is convinced that he is not son of the father we thought; a cousin still perhaps, but with no record at all?)

Despite multiple Henry (and John) Clays, I found I do have a cousin relationship to Senator Henry Clay.

More than names on a chart

Finding the names to fill out charts was a treasure hunt, but ultimately unfulfilling. The names and dates offered little insight into actual lives, so I began collecting stories.

By 2011, I had so many interesting stories, in addition to the charts, that I compiled the notes into a one-hundred-plus-page history for my cousins. One of my favorite stories was of Cecily Jordan, and her connection to The Tempest. I thought she was one of many interesting ancestors of my maternal grandfather Henley (others were also in Virginia colony). Discovering a connection between Cecily and my maternal grandmother Brashear’s distant aunt was a delight. There were both Brashears and Henleys in 1600s Virginia, then by the 1700s the familes lived in different colonies. They didn’t intermarry until my grandparents married in Tennessee in 1920. Finding that connection was the first of many such stranger-than-fiction coincidences.

In 2020, after finishing writing my book Eastclifff: History of a Home, I thought I would take a few weeks and update the family history. The amount of additional information, both true and false, available online was now overwhelming. The best online leads were journal articles, names of well-researched books, and copies of original source material. I realized my project was going to take years, and I was back where I began, searching old documents.

Returning to the methods of the past, and to Cecily

Adventurers of Purse and Person, Virginia 1607–1624/5 is an excellent resource of Jamestown residents. It includes the Musters of Virginia 1624/25 and expands lines of those inhabitants as found.

The muster, a census with names and arrival dates, was taken the month after December 1624, and dated January 1624. At that time, the new year began with the spring equinox, so we now consider that date as 1625. (This is another complication that can lead to errors in genealogical research. If more than one researcher “corrects” the listing to current usage, the date can become off by multiple years.)

First published in 1956, Adventurers of Purse and Person is a compilation of articles from the William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine. (The quarterly is an excellent resource.) The edition I used was John Frederick Dorman, ed., Adventurers of Purse and Person, Virginia, 1607-1624/5. Fourth Edition. Volumes One, Two and Three, Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing, 2004–2007.

As I searched this and in other reputable resources for documentation of what I “knew for sure” that might not be true, I could find no evidence that Cecily Jordan was my ancestor. Instead I found a surprising connection between Cecily and my paternal grandmother’s ancestor John Clay. And I found that three of my grandparents had ancestors in Jamestown in the 1600s.

Other research showed that all four of my grandparents had ancestors who fought in the American Revolution. This perplexed me until I learned that the land in Middle Tennessee where both my parents were born was land given to Revolutionary War soldiers as payment for their service.

When I began writing History with a Southern Accent, I included some of my fascinating ancestors, as I feel I have the right, perhaps even the obligation, to tell their stories. I also include Cecily and others, and hope their real descendants will understand that I tell their stories with respect and admiration.