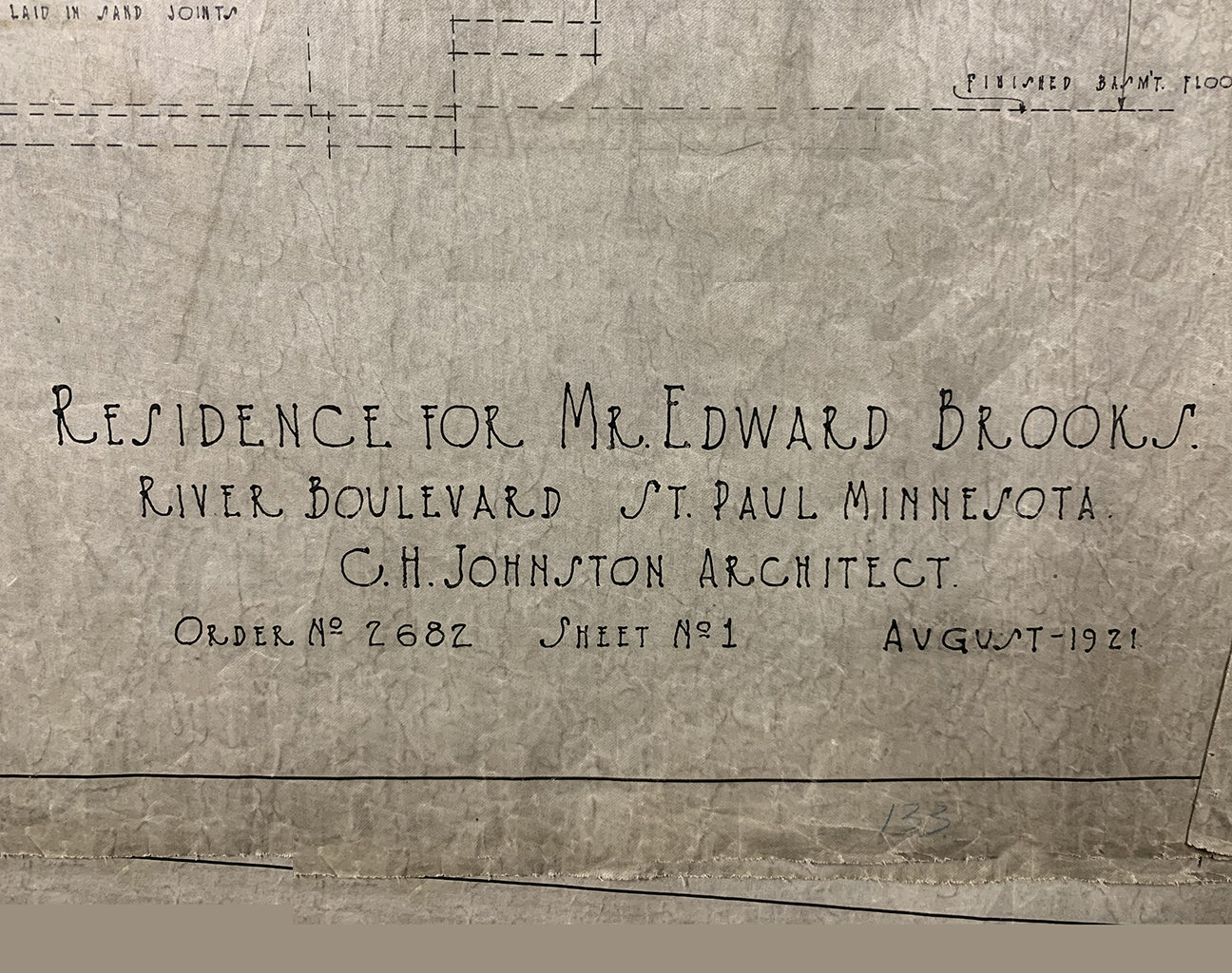

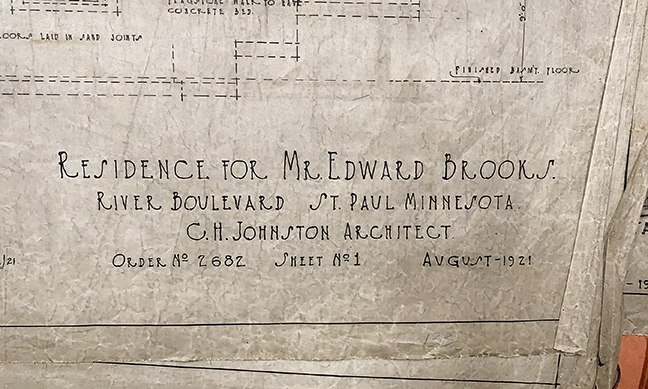

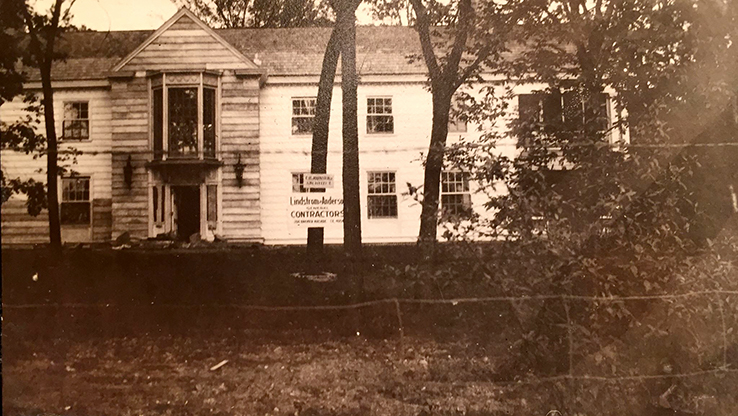

Young Edward Brooks hired his friend, Howie, to design his home in 1921. Howie would become a well-known architect, C.H. Johnston Jr.

Over time, whether inadvertently or not, Howie’s more famous father became known as the architect of Eastcliff. The famous father was, indeed, the architect of record, as his son worked in his firm. Eastcliff may have been the first home that the two men, one a famous architect, one who would become a (slightly less) famous architect, worked on together.

Clarence Howard “Howie” Johnston Jr. was the second son of Clarence and May Thurston Johnson. (As in the Brooks family, the first son was named for his mother’s family, and the second son was named for his father.) The oldest son, Cyrus Thurston “Thur” Johnston, received an engineering degree from MIT and worked in private practice for four years before joining his father and brother as engineer in the Johnston firm in 1915. He died in 1920, at age thirty-three, from influenza.

C. H. Johnston Jr. (1888–1959) began working for his father’s firm in 1906. He left the firm for a course in architecture at Columbia (1908–1910), and again later to serve in World War I (1917–1918), but otherwise remained with the firm until retirement in 1956. In 1936, he became president of the firm, renamed C. H. Johnston, architects–engineers.

Shortly after Eastcliff was built, another lumberman, Archibald Jefferson, hired Johnston Jr. to design a stone mansion near Eastcliff at 71 Otis Lane. That home was built in 1925.

Glensheen, a mansion in Duluth that, like Eastcliff, is owned by the University of Minnesota, was designed by C.H. Johnston Sr.

Glensheen, from https://glensheen.org/

Glensheen has been the subject of several books, and even a 2015 musical titled, simply and eponymously, Glensheen. Glensheen has more notoriety, not only as a much larger home, but also because two murders were committed there. In 1977, someone broke into Glensheen and bludgeoned nurse Velma Pietila with a candlestick, and then smothered heiress Elizabeth Congdon with a satin pillow. No murders have ever taken place at Eastcliff (except, well, maybe that time our dogs caught a rabbit). This is the first book about Eastcliff.

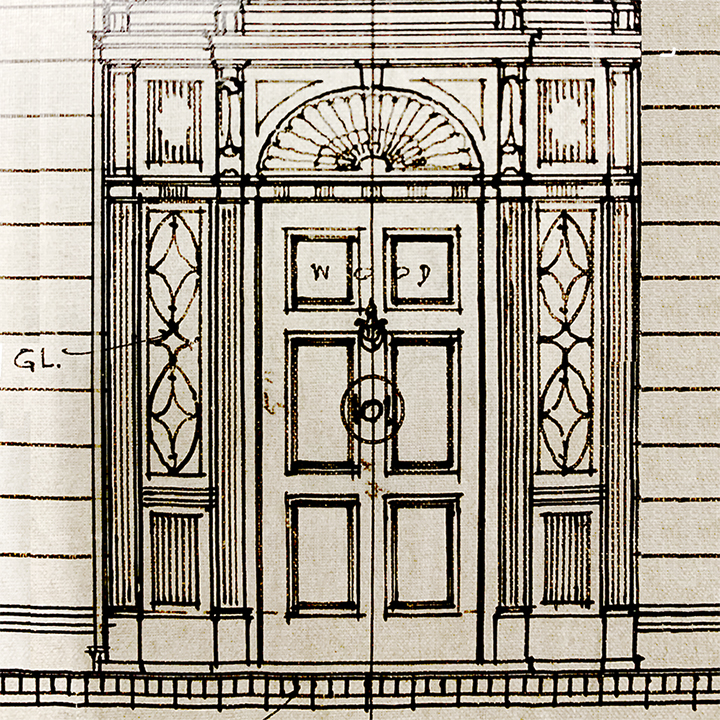

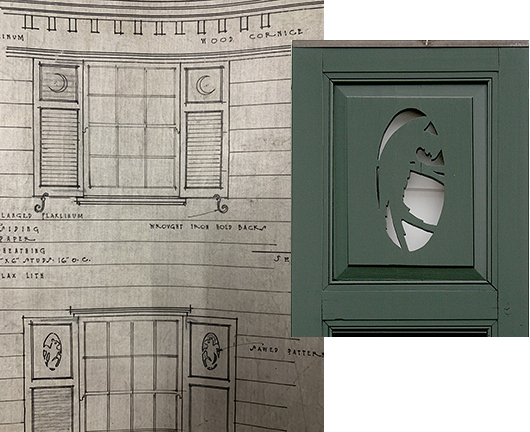

Photographed by the author from drawings in the University of Minnesota Engineering Archive, and from the house

One of the questions that people regularly asked me about Eastcliff concerned the shutters. “What is that?” they would ask. Then after my reply, “Are you sure it’s a parrot?” I’m sure. The parrot has its wing high, and its head low. I think that is to fit in the oval, but it does give it a resemblance to a vulture. “Why a parrot?” I don’t know. “Did they really love birds?” you may wonder. (Inside the house, the dining room was later painted with a variety of birds, and you’ll read in the book about a peacock.) Again, I don’t know.

I read of a “cut-out shutter craze” in 1920s colonial revival houses. It was the thing. Johnston’s architectural drawings include the parrot on all the lower shutters, as well as a crescent moon on the second story windows, and a detail drawing of a shutter with a squirrel. It seems to me that the architect made suggestions, and the Brooks chose option one (the parrot) rather than option two (the squirrel), and nixed the crescent moons completely.

Please note: The above text was edited from Eastcliff: History of a Home due to lack of space. It is intended as a supplement to the book.