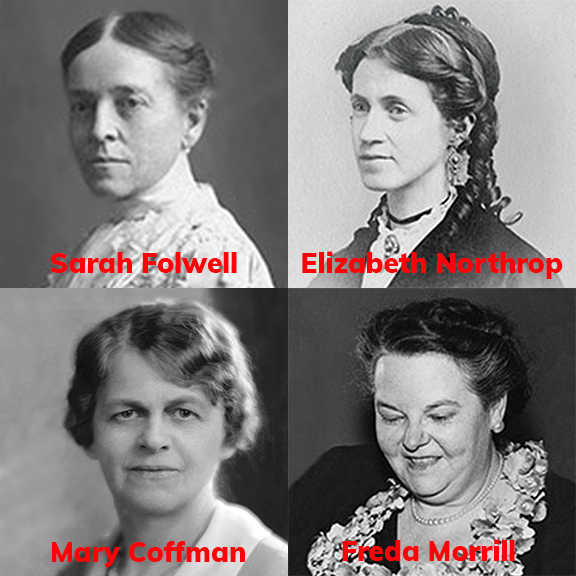

The four partners shown above were the longest serving at the University of Minnesota:

Sarah Heywood Folwell (1838–1921) met William Watts Folwell at Hobart College, where her uncle was president. Perhaps her family background influenced their future. William Folwell became the first president of the University of Minnesota. The Folwells served 15 years, 1869–1884.

Anna Elizabeth Warren Northrop (1835–1922) served with her husband, Cyrus Northrop, for 25 years, 1884–1911. Elizabeth and Cyrus, like each of the first four presidential couple, had three children. The Northrops endured great sorrow as parents as they outlived all their children.

Mary Farrell Coffman (1877–1957) married her hometown (Paoli, Indiana) high school principal, Lotus D. Coffman. He became president of the University of Minnesota and they served for 18 years (1920–1938), until his sudden death while in office. While President Coffman has been justifiably criticized for his acquiescence to discriminatory practices that harmed Black students, the couple welcomed all students to events in their home, and Mary was known for her concern for student wellbeing.

Freda Rhodes Morrill (c.1894–1977) served with her husband James Lewis Morrill for 15 years (1945–1960). He had previously been president of the University of Wyoming. They both grew up in Marion, Ohio, and while the president was known by almost everyone as Mr. Morrill; Freda called him Lew.

(Source for photos, and for photos of the twelve partners at the top of the page: https://www.minnesotaalumni.org/stories/first-mates)

The Lives of Presidential Partners in Higher Education Institutions

In 2016, before writing the Eastcliff book, I joined with two other researchers (Darwin D. Hendel, PhD, and Gwendolyn H. Freed, Phd) to research, write, and publish a report titled, “The Lives of Presidential Partners in Higher Education Institutions.” We had survey responses from 461 partners, including 77 who identified as male. This was the largest study ever done of presidential partners. The full report is available at

https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/183467

I was particularly interested in asking about official residences. I had discovered that the chancellor’s residence that I had memorably visited when I was a college student had been deemed not worth the cost of upkeep. It was offered for sale, and was sitting empty and unsold. (It did sell years later, at a greatly reduced price.) During our tenure at Minnesota, another official residence was torn down. Meanwhile, at other institutions, new replacement houses were being built.

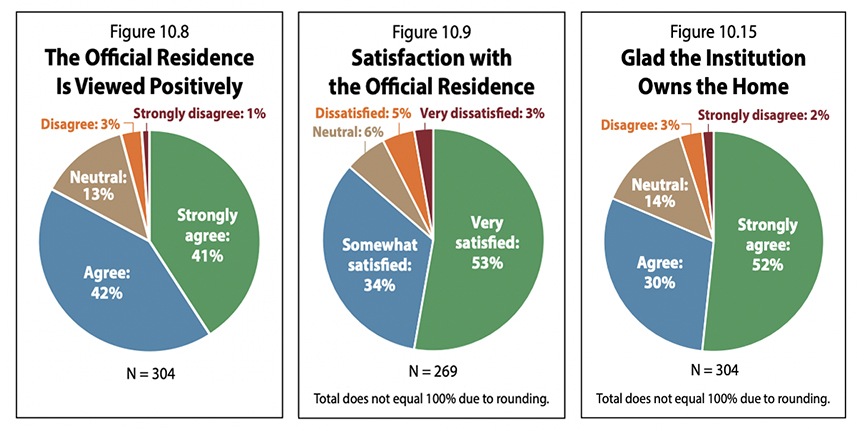

In the survey, we asked partners three questions to ascertain the perceived value of the official residence: how they thought the residence was perceived by others, their own satisfaction with the residence, and whether or not they were glad the institution owned the residence. In response to each question, as shown in the graphs, the positive responses totaled over eighty percent and less that ten percent of the partners’ responses were negative.

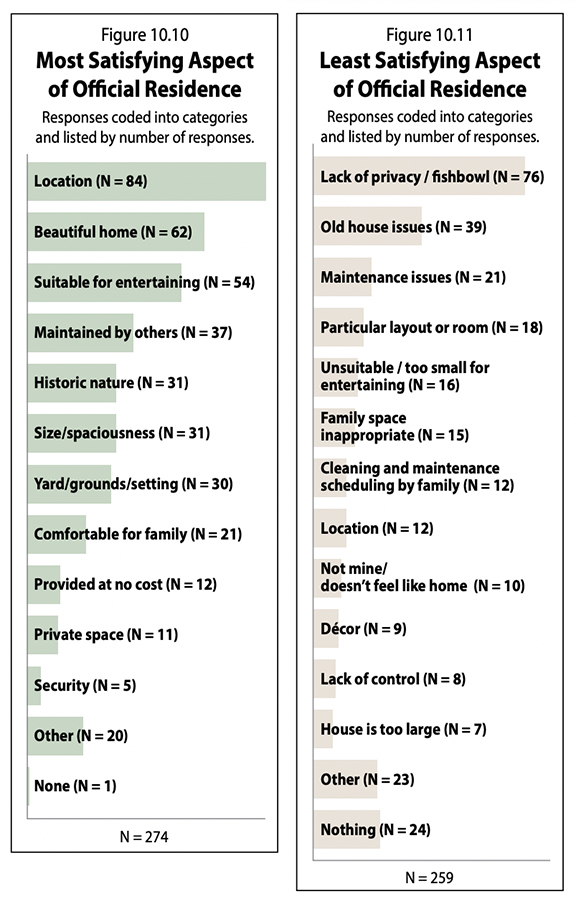

In open-ended responses to the most and least satisfying aspects of the residences, the locations of some residences were clearly more favorable than others, as was their suitability for entertaining. The lack of privacy was the greatest concern overall.

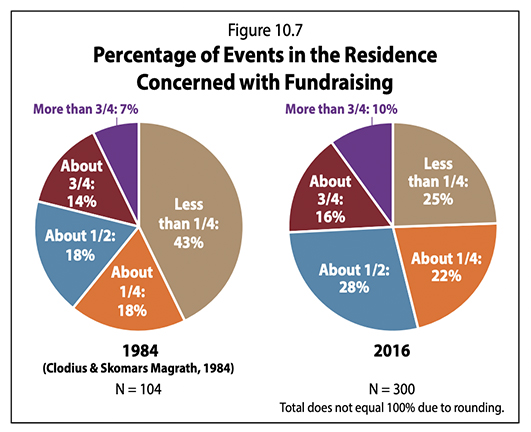

In comparison to Diane’s Skomars survey of presidential partners a third of a century earlier, there was significantly increased use of the residence for institutional fundraising.

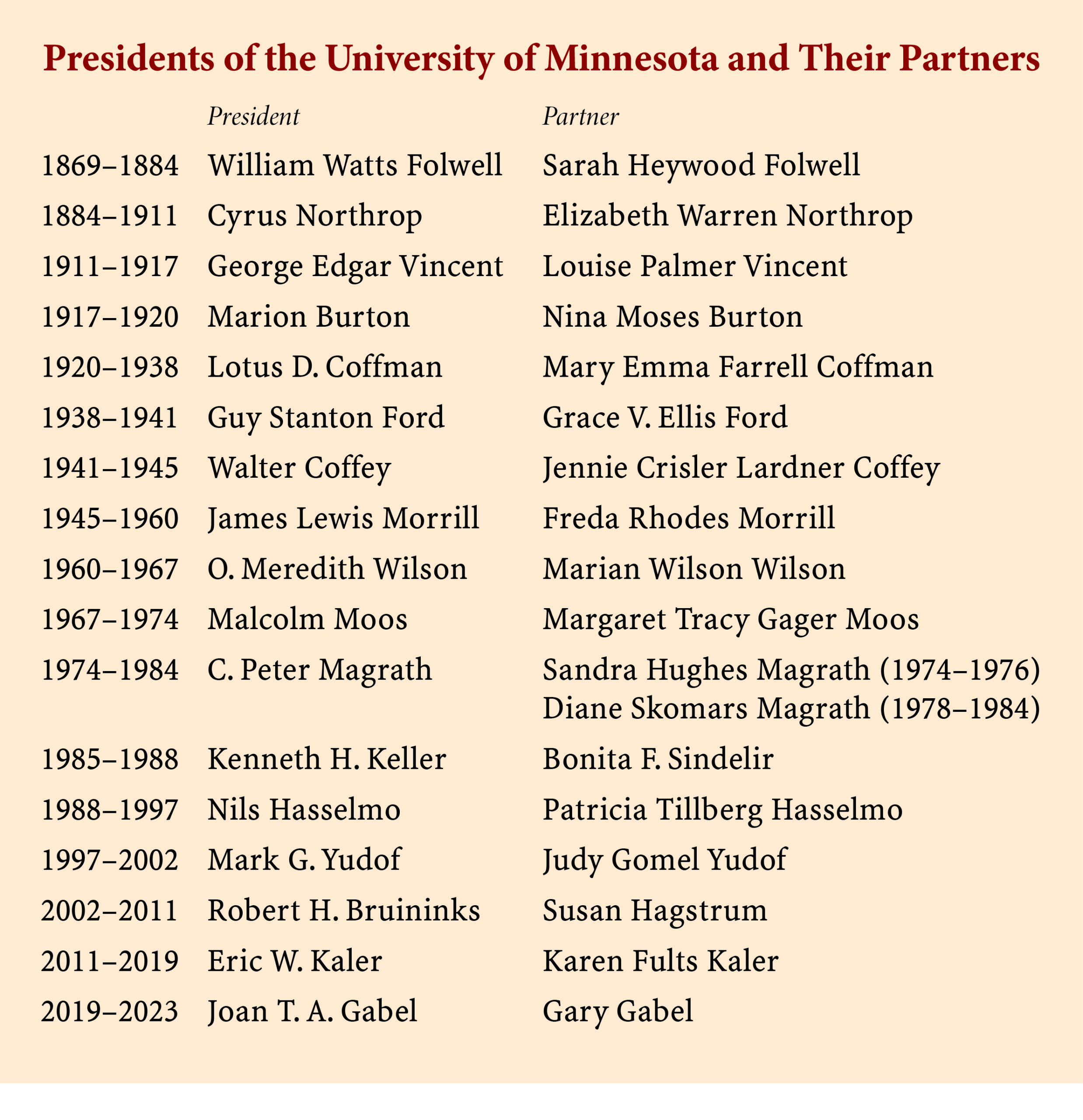

Listing the Partners

During my husband’s University of Minnesota presidency, I lamented that the university’s website had nice biographies of each of the former presidents, but their spouses were not included. Not even their names. I felt strongly that these (at the time all) women had devoted a lot of time and energy in service to the University, and deserved to recognized.

I sought to have all the University of Minnesota presidential partners listed online. My efforts led to an article in Minnesota magazine, but I was not able to get the list onto the website. When I checked recently, the presidents have now been removed from the website, as well. As I have realized with many things in life, the people who care the most should quit requesting and take on the responsibility themselves. So here the partners are, online at last. Please see https://www.minnesotaalumni.org/stories/first-mates for a little more information, or read Eastcliff: History of a Home for a lot more information.

Presidents of the University of Minnesota and Their Partners

1869–1884

William Watts Folwell

Sarah Heywood Folwell

1884–1911

Cyrus Northrop

Elizabeth Warren Northrop

1911–1917

George Edgar Vincent

Louise Palmer Vincent

1917–1920

Marion Burton

Nina Moses Burton

1920–1938

Lotus D. Coffman

Mary Farrell Coffman

1938–1941

Guy Stanton Ford

Grace Ellis Ford

1941–1945

Walter Coffey

Jennie Lardner Coffey

1945–1960

James Lewis Morrill

Freda Rhodes Morrill

1960–1967

O. Meredith Wilson

Marian Wilson Wilson

1967–1974

Malcolm Moos

Margaret Tracy Gager Moos

1974–1984

C. Peter Magrath

Sandra Hughes Magrath

(1974–1976)

Diane Skomars Magrath

(1978–1984)

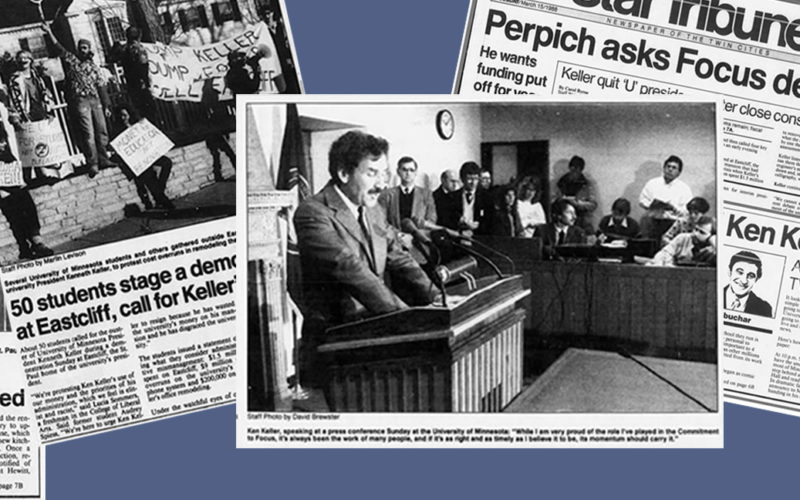

1985–1988

Kenneth H. Keller

Bonita F. Sindelir

1988–1997

Nils Hasselmo

Patricia Tillberg Hasselmo

1997–2002

Mark G. Yudof

Judy Gomel Yudof

2002–2011

Robert H. Bruininks

Susan Hagstrum

2011–2019

Eric W. Kaler

Karen Fults Kaler

2019–present

Joan T. A. Gabel

Gary Gabel

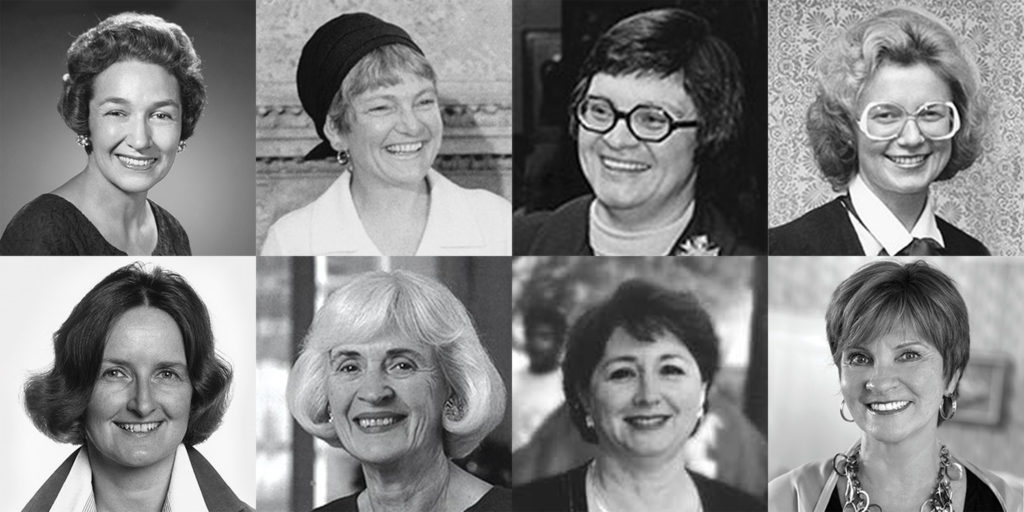

Top row: Marian Wilson, Tracy Moos, Sandra Magrath, Diane Skomars Magrath

Bottom row: Bonita Sindelir, Pat Hasselmo, Judy Yudof, Susan Hagstrum

Photos from https://www.minnesotaalumni.org/stories/first-mates

Meeting the Partners

Meeting others who have served in the role of presidential partner, and particularly those who preceded me in the role at the University of Minnesota, has been a real joy for me. I enjoyed getting to know Tracy Moos, Diane Skomars, Bonita Sindelir, Judy Yudof, and Susan Hagstrum. While Pat Hasselmo died before we returned to Minnesota, I read a lot about her that I really admired her felt like I knew her. I enjoyed knowing Nils and their daughter, Anna.

In addition to Minnesota partners, I’m grateful to have had the opportunity through presidential partner groups of higher education associations to meet many wonderful people serving in this role, most of whom I would have never met otherwise. Two special people served at schools that are Gopher competitors, Marcia Kelley at University of North Dakota, a hockey competitor, and Hanns Kuttner at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, a competitor to the Gophers in everything. Hanns and I, along with two mascots and two presidents, had a memorably fun time at the Minnesota State Fair, as well as at AAU meetings. Marcia and I, and our dear friend Laura Voisinet, were the three musketeers and chairs in succession at APLU, and were then joined by younger sister/fourth musketeer, Monika Moo-Young.

As I returned to the presidential partner role at Case Western Reserve University in 2021, I am again attending AAU meetings. I have enjoyed getting to know Gary Gabel (now at UMN) and Michael Snyder (previously at CWRU). It’s a special connection to know people who served in the same role while living in the same house.

Through reading Eastcliff: History of a Home you will meet all of the partners who have lived at Eastcliff. Several paragraphs from the section on partners were edited from the book and are below.

Diane Skomars Magrath: After Peter and Diane Magrath’s 1978 wedding, Diane quit her job at the University and took on “Partner of the President” with equal professional energy. Peter Magrath’s salary at the time was $70,000 a year. He diverted $25,000 of that to Diane as her salary. Diane explained that prior to her marriage she had been earning $22,000 per year. After resigning from her position, she found she was still working but not getting paid; she missed her paycheck. “Peter said that what was his was mine, but I didn’t feel right about that. I didn’t want a token allowance. So I sat down and wrote a job description and we agreed on a salary.”

In 1979, the Minneapolis Tribune ran a front-page article titled, “’U’ President Magrath, wife work together as employer-employee.” Her duties were listed as three or four meetings a week, arranging invitations, catering, and guest lists, giving speeches, and organizing a television program about the University titled Matrix. In the article, Peter is quoted saying, “One of the joys of my life is working with her. I function better this way. The fact that we can do some things together makes it more bearable. And if my personal life is happy, everything else is okay.”

Joe Kimball, “‘U’ president Magrath, wife work together ad employer-employee,” Minneapolis Tribune, December 26, 1979.

When Peter became president of the University of Missouri system, they continued their payment system. (She received $30,000 of his $100,000 salary.) Peter wrote, “The pay issue is controversial, and that’s healthy because it promotes intelligent discussion. I pay you because I believe that ‘women’s work’ is undervalued, and that our society tends to regard jobs as unreal unless money is attached to them. This is both unfortunate and degrading to the whole concept of volunteer work contributed by both men and women.”

Diane Magrath and C. Peter Magrath, “The Dear Peter, Dear Diane Letters,” AGB Reports (Association of Governing Boards), March/April 1985.

The pay issue was controversial, even though it didn’t cost either university a penny. News of the arrangement at Missouri resulted in an article in the Chicago Tribune quoting Diane as explaining, “Whenever something is considered traditional ‘women’s work’ it’s usually misunderstood and undervalued. That truth has been a harder problem for me to face than living a public life. It hurts.”

Carol Kleiman, “President’s spouse earns her keep, too,” Chicago Tribune, February 18, 1985.

Articles on the same subject appeared in the Kansas City Star (February 19, 1985) and in the Christian Science Monitor international newspaper (March 8, 1985).

The article that was undoubtedly read by the most people was by Erma Bombeck, who wrote a syndicated column that appeared in 900 newspapers nationwide. Bombeck, a bestselling author and popular humor columnist from 1965 to 1996, wrote that the pay was a good idea, and that ministers, military men, etc., should split their paychecks, as well. “If Ms. Magrath sets a trend,” she wrote, “don’t be surprised to find out wives are a luxury that most men cannot possibly afford.”

Erma Bombeck, “The wives behind the men.” News Group Chicago, Inc. News America Syndicate, February 11, 1985.

Erma Bombeck had a quote that reminds me of Tracy Moos arrival at Eastcliff: “All of us have moments in our lives that test our courage. Taking children into a house with a white carpet is one of them.” Ms. Bomback, like University of Minnesota great Harvey Mackay, expressed her philosophy in her clever book titles, including The Grass Is Always Greener over the Septic Tank and If Life Is a Bowl of Cherries, What Am I Doing in the Pits. Harvey Mackay’s similarly evocative titles include Swim with the Sharks Without Being Eaten Alive, Dig Your Well Before You’re Thirsty, and Beware the Naked Man Who Offers You His Shirt.

Bombeck later wrote Diane a lovely note explaining, “I was drawn to the story about you for several reasons. First, you seemed to be a very bright human being, and secondly, it takes a certain amount of courage to mother a new theory and take the chance of being laughed at. I certainly was not laughing when I wrote the column. I agree with you one hundred percent. . .”

Erma Bombeck, personal correspondence with Diane Skomars, Magrath, May 1, 1985.

Pat Hasselmo: Professor Clarke A. Chambers interviewed many former University administrators after they left office. When he interviewed Nils Hasselmo (March 16, 18, and 19, 1998, in Tucson, Arizona), Nils spoke about his wife and partner, and suggested Chambers interview her as well, which he did. Patricia Hasselmo was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on March 23, 1998, in Tucson, Arizona. (More text from the interviews is in the book. In both here and in the book, I have edited the text very slightly to remove Chambers comments.)

Nils said,

“Pat and I work very much as partners. We had events practically every day where we represented the university jointly and Pat was working practically full time for the university as well. Clarke, I would encourage you to interview Pat and she’s quite willing to do that. I think that’s an important case history of the presidential spouse and the demands that are placed on a spouse, especially one who is willing to enter into those kinds of responsibilities. . . Pat worked very hard, first of all, as hostess at Eastcliff, hosting between 4,000 and 4,500 people every year. She was always there for me and criticizing me and telling me I was all wrong and telling me, sometimes, that I was right and that I should hang in there and do what I had set about to do. I discussed a lot of issues with Pat and got good advice from her. . . She played a major role in general public relations and, especially, in fund raising and, personally, had a major role in raising an endowment of about $700,000 for Eastcliff for its maintenance.”

Pat spoke about the issue of spouse recognition, and opposition or disinterest in it:

“By the way, some of the chairs of the Board of Regents were very interested in this issue. The woman board chair, who was there part of the time, was very disinterested, which was interesting to me. . . . The regents did pass this; but, to my surprise and distress, there were a number of letters to the editor, mostly in the Minnesota Daily but some even in the newspaper in the larger community, in which the writers objected very strenuously to the notion of a title for this spouse and any recognition, on the basis, I guess, that the spouse hadn’t deserved any of this on her own. She was only in there by virtue of being married to the president. I think that was the source of the irritation. All of these letters were written by people within the university, either staff or faculty, who were women. I found that so distressing and such a downer that women are so likely to attack one another on fairly minimal pretenses.”

I know how painful this realization must have been for Pat, as I relate to her as a kindred spirit and feminist. I have noticed the same issue Pat lamented. There (still) seem to be some working women who have complicated feelings about women who are volunteering, particularly if they are volunteering due to their husbands’ positions. I’m not sure if “complicated feelings” is correct, as how can I know how they feel? Nonetheless, there was a lack of support that was, and is, as confusing and distressing to me as it was to Pat. I have been very candid in writing this book, but this is one of the most painful intimacies I can share. I have only spoken openly about this to my dear friend Diane Skomars, and she assured me that it’s not just me.

Pat spoke about the then contentious issue of paying partners for their work:

“There were many of the spouses [in NASULGC] who felt that they ought to be paid for the time and effort that they were putting into this role. You can argue it because, for example, when a woman is named president of these institutions, the male spouse does not, usually, assume–once in awhile–the role that a wife would have. They usually do not so, then, the university goes out and hires someone. . . to do all the things that the spouse is doing. They are paid, so it’s perfectly acceptable then but not when it’s a spouse. This is a point of concern for the spouses and it’s always discussed to a degree whenever we are together as a group. In the private institutions, they’ve gone further in terms of financially rewarding the spouses. . . It’s a terribly tough issue and it’s one that most institutions are not going to address.”

Susan Hagstrum: Susan is quoted in the book as saying she quit working outside the volunteer role because she was “missing all the fun.” At the end of Bob’s presidency, Susan expanded on her decision to leave paid employment:

“I had a very successful business, and I chose to set it aside. Toward the end, I was helping a number of schools work with the voluntary desegregation initiatives that were funded in the late ’90s. I was going to Wilmar, Worthington, New Ulm, Anoka, but I was missing the nighttime stuff at Eastcliff. Bob asked me if I’d be willing to set aside the business. I have no regret at all about doing so.”

Tim Brady, “Life’s Currents,” Connect (magazine of the University’s College of Education and Human Development), Summer 2011.

It seems to me the concern about partners’ pay has decreased, or at least partners have quit talking about it in association meetings. I think that now, particularly as more men enter into the role, partners have more choice in how much time they devote to the role. I understand that it must be particularly frustrating to be required to work without being compensated. I enjoyed the role at Minnesota, and continue to do so at CWRU. I was thrilled to have a parking permit at Minnesota, so I didn’t have to pay to volunteer. Later, Eric told me he paid for his parking permit, and said he thought he also paid for mine, but at the time I felt appreciated. (Unlike partners, University of Minnesota regents receive free parking for life.)

In the survey done in 2016, twelve percent of partners were paid for work in the role of presidential partner (seven percent in public institutions; seventeen percent in private institutions). While analyzing the survey responses, I wished we had asked more about this response. At least some of the twelve percent had been in full-time paid positions previously in their institutions and a portion of their salary came from a different source after they were unable to continue full-time in their previous roles (such as Bonita Sindelir, who took a fifty percent pay cut to volunteer in the role but was not compensated for the loss). Diane has been the only partner at Minnesota, to date, to be paid in the role. However, one could argue that since her salary didn’t come from the University but from her husband (and her social security tax may have resulted in lower take-home pay for their family), she might not be included in this twelve percent. Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that those paid reported the highest level of satisfaction in the role.

Please note: The above text was edited from Eastcliff: History of a Home due to lack of space. It is intended as a supplement to the book.